1,722 days, 2,676 entries ...

Newsticker, link list, time machine: HOLO.mg/stream logs emerging trajectories in art, science, technology, and culture––every day

“Our modern machines feel too much like the anonymous, minimalist interior of a business hotel. Small wonder, then, that we yearn for the soulful log cabins of yore.”

Finnish media scholar Markku Reunanen revisits early DIY computer music culture in a newly translated paper on the rise of trackers. Defined by the limited sound capabilities of Commodore and Atari home computers in the 1980s and ’90s, trackers offer a command-based way of making music where audio channels are mapped onto columns—tracks. In his research, first published in Finnish in 2019, Reunanen draws on technical analysis and creator interviews to map a tracker family tree and the paradigm’s wider legacy.

A newly discovered copy of Andy Warhol’s now-famous pixel portrait of Blondie singer Debbie Harry will go on sale for a minimum of $26 million USD, artnet reports. Created at the 1985 New York City launch event of the Commodore Amiga, the print and a Warhol-signed floppy disk with ten works resurfaced via former Commodore engineer Jeff Bruette who aided the Pop art icon in his computer experiments. The piece was actually produced during rehearsal, Bruette reveals—the portrait Warhol drew live was “horrible.”

Retro computing blogger Josh Renaud reports the recovery of long-lost algorithmic music software developed by American-Israeli inventor and cartoonist Yaakov Kirschen in 1986. Magic Harp was a set of six thematic music disks to be bundled with the Commodore Amiga, each dedicated to a different genre. Found was a beta version of “baroque,” where a Bach-like “artificial personality” conducts digital organs and spinets (image). After the deal with Commodore fell through, Kirschen’s innovations were largely lost to obscurity.

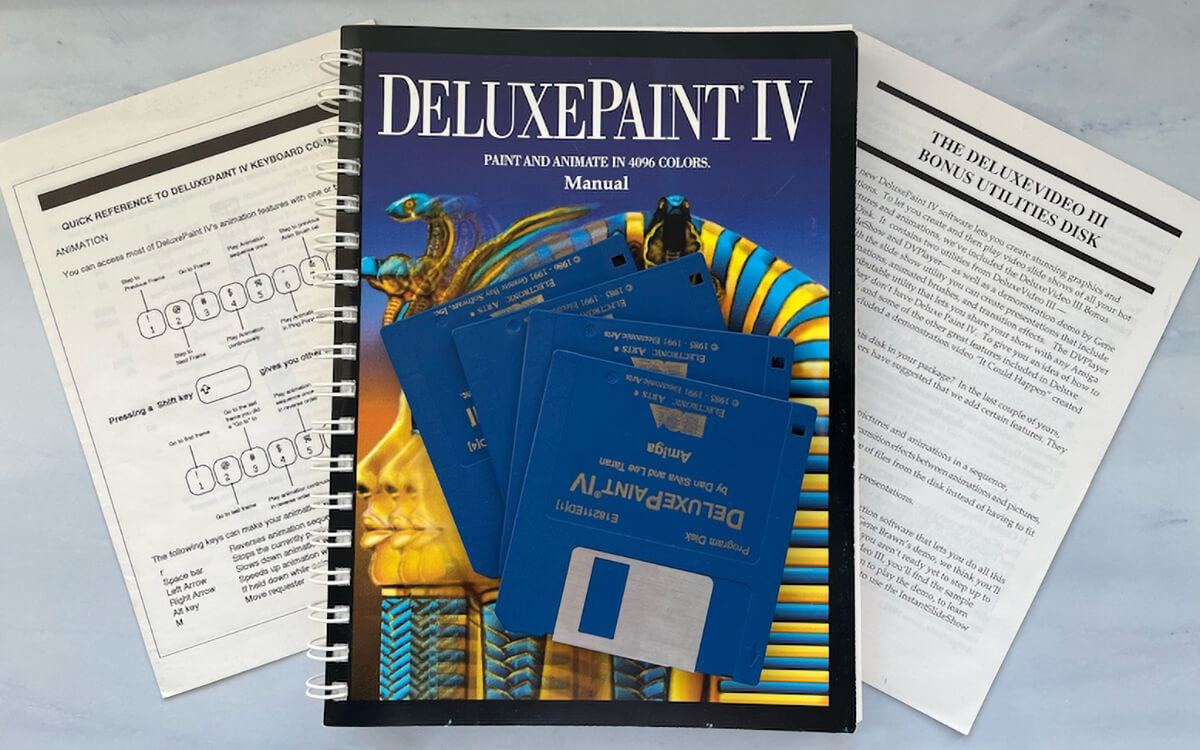

In a love letter to Deluxe Paint, the popular pixel editor Electronic Arts published from 1985 to ’95, Swedish programmer Carl Svensson dissects and celebrates the package’s powerful drawing, animation, morphing, and colour cycling features that defined the workflow of pixel artists and game developers well into the PlayStation era. “If you’re an old school DOS, Amiga or even console gamer, it will have helped create some of your fondest memories,” writes Svensson.

The auction for “Keith Haring: Pixel Pioneer” concludes, bringing in $1.6M in sales across five lots. Undeterred by faltering NFT sales, several astute collectors swooped in to acquire the late artist’s trove of Commodore Amiga drawings. Created in the winter and spring of 1987, they showcase Haring’s signature exhuberent figures and vivid colour palettes, as shaped by the limited graphic capabilities (320 x 200 resolution, 32 colours) of the Amiga (image: Untitled #2 (April 16, 1987)).

“The Haring NFTs demonstrate that the smart contract can be a flexible tool, using metadata and code to accommodate the various needs and contexts of digital art.”

“The Amiga drawings are significant because they were created at the dawn of the consumer computer age. Even then, Keith knew that computers were going to be important to people’s lives as their capabilities continued to advance.”

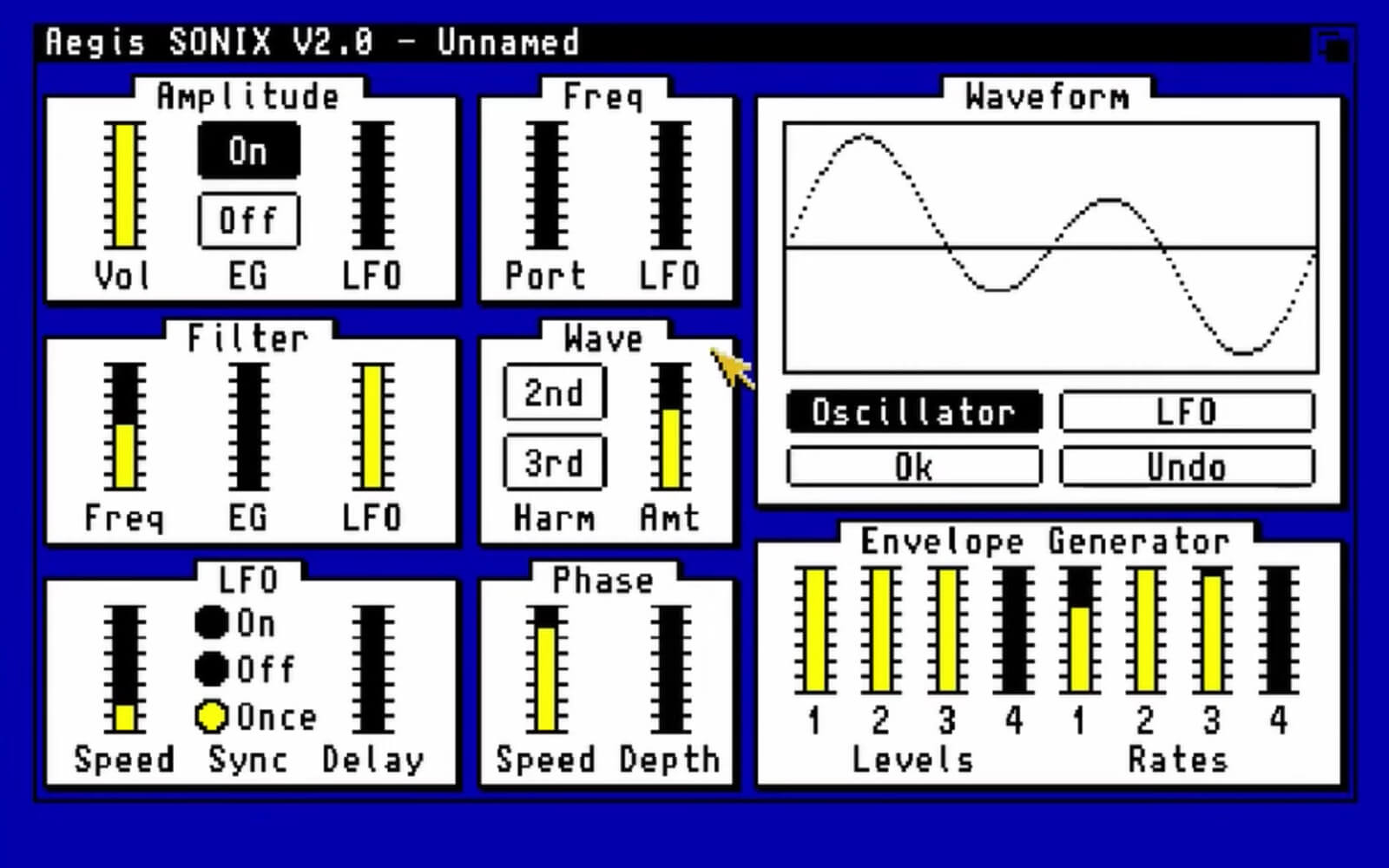

British composer and vintage computer music connoisseur Paulee Alex Bow takes to his Magical Synth Adventure! YouTube channel to revisit obscure software instruments on the Commodore Amiga, a 16bit home computer platform launched in 1985. Introducing viewers to the unique capabilities of the system’s 4-channel sound chip, Paula, Bow demoes a variety of early real-time soft synths including Aegis SONIX (1986, image), Sonic Arranger (1992), and OctaMED (1989-97, “my happy place”) that enthusiasts experiment with to this day.

Journalist Steffan Powell reflects on Helsinki’s dominance in mobile gaming, citing the demoscene as a key catalyst. Before Angry Birds Nokia put the city on the map, Powell writes, tracing local tech aptitude to 1990s and ’00s—still burgeoning—demoparty culture that fuelled domestic creation (image: CNCD, Closer, 1995) and attracted programmers from afar. The demoscene nurtured a culture of doing more with less, or as quoted executive Sarita Runeberg puts it: “Finns have been tech geeks since forever!”

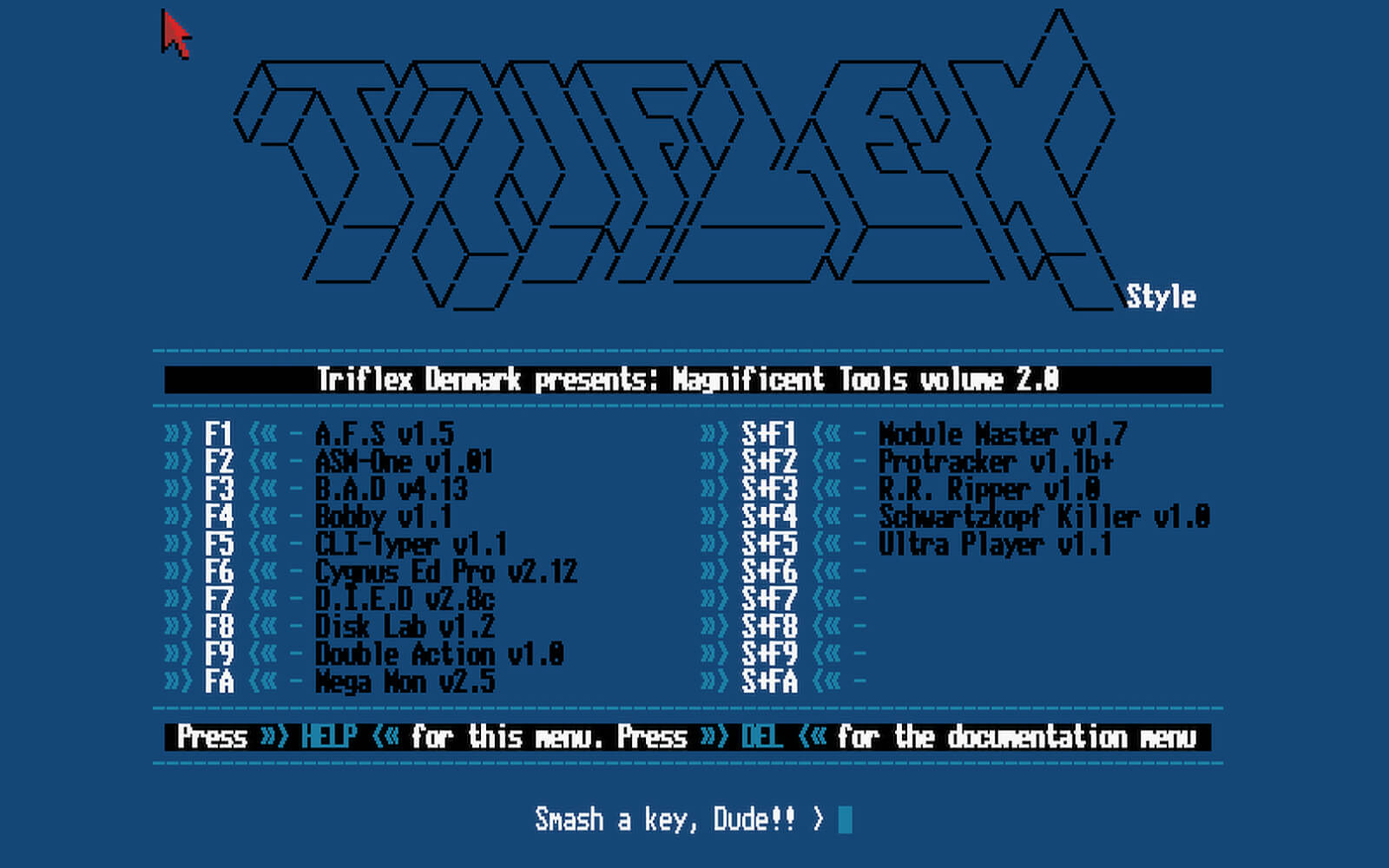

In a blog post, Swedish programmer and hobby media archaeologist Carl Svensson revisits “the colourful charm of Amiga utility disks.” Compiled by demosceners to circulate self-made and (cracked) commercial tools in the late 1980s and early 90s, these bootable software packs came in eccentric flavours—from hacked system interfaces featuring ASCII art to rich, audiovisual presentations. “If you wanted to make a demo, you’d be all set with just a handful of these disks,” concludes Svensson.

“The thing about the Amiga bassline is that it was constant volume, it didn’t waver. So when you pulled it up to the maximum volume that you could press on to vinyl, it made it, well, phat as fuck.”

Tamlin Magee revisits the 16-bit heyday of the early ’90s, when the sound and sampling capabilities of Amiga home computers were central to a burgeoning electronic music scene. “It was the poor man’s studio,” recalls Marlon Sterling, AKA drum’n’bass producer Equinox, whose recently released Early Works 93-94 were made using the OctaMED music tracker when he was only 15. (image: Sterling during an Amiga music restoration session with fellow UK producer Bizzy B)

In response to Lionel Dricot’s call for a “computer built to last 50 years,” Swedish programmer Carl Svensson argues that such a “ForeverComputer” already exists: the Commodore Amiga 1200 (image), a portable 32bit platform launched in 1992, meets Dricot’s criteria of being “sustainable, decentralized, offline-first and durable,” while offering many modern features and a massive software library. Bonus: “No notifications, no distractions, no surveillance.”

Demosceners celebrate the 30th anniversary of the inaugural edition of The Party, a landmark meetup of ~1,200 young computer enthusiasts in Aars, Denmark, that would inspire similar creative gatherings—demoparties—across Europe for years to come. The three-day jam saw the release of many 16-bit classics such as Hardwired, Odyssey, and Voyage, and, expanding into rave and videogame culture in subsequent years, would draw up to 5,000 annual visitors before its demise in 2002.

“Sadly, Christie’s missed the huge opportunity to get this right. However one feels about NFTs, Warhol’s Amiga images are a unique discovery. In their haste to take advantage of the NFT hype, they neglected to do the basic research that these works deserved.”

“I’ve spent a lifetime wondering why the Amiga ‘Insert Workbench’ boot image looked kinda wonky,” confides Panic Inc. co-founder Cabel Sasser on Twitter. ”I always assumed it was hand-drawn pixel art.” It turns out it’s vector art. A surprised Sasser reveals that just 412 bytes of vector drawing instructions were needed to render the iconic (Sheryl Knowles-created) hand-held floppy disk. “Incredible!” Meanwhile, media artist Golan Levin verified the 1985 vector data with a “quick-and-dirty” Processing sketch.

Software engineer and electronics hacker Ian Hanschen shares his vast bitmap font collection that he pulled from various demoscene archives over the years. The catalog includes hundreds of glorious pixel letterform sheets created on the Commodore 64, Atari, and Amiga home computers in the late 1980s and early ’90s. “I don’t remember where much of this collection came from,” Hanschen writes about the missing metadata. “I just thought after finding a few of these [archives] had died that I should make it available.”

Daily discoveries at the nexus of art, science, technology, and culture: Get full access by becoming a HOLO Reader!

- Perspective: research, long-form analysis, and critical commentary

- Encounters: in-depth artist profiles and studio visits of pioneers and key innovators

- Stream: a timeline and news archive with 1,200+ entries and counting

- Edition: HOLO’s annual collector’s edition that captures the calendar year in print