Variations: 1960-1968

1960–1968: Machine Imaginaire to Machine Réelle

“What fascinated Molnar about computers was more practical than speculative or futuristic. It was their capacity to compute, and to do so accurately, quickly.”

“What fascinated Molnar about computers was more practical than speculative or futuristic. It was their capacity to compute, and to do so accurately, quickly.”

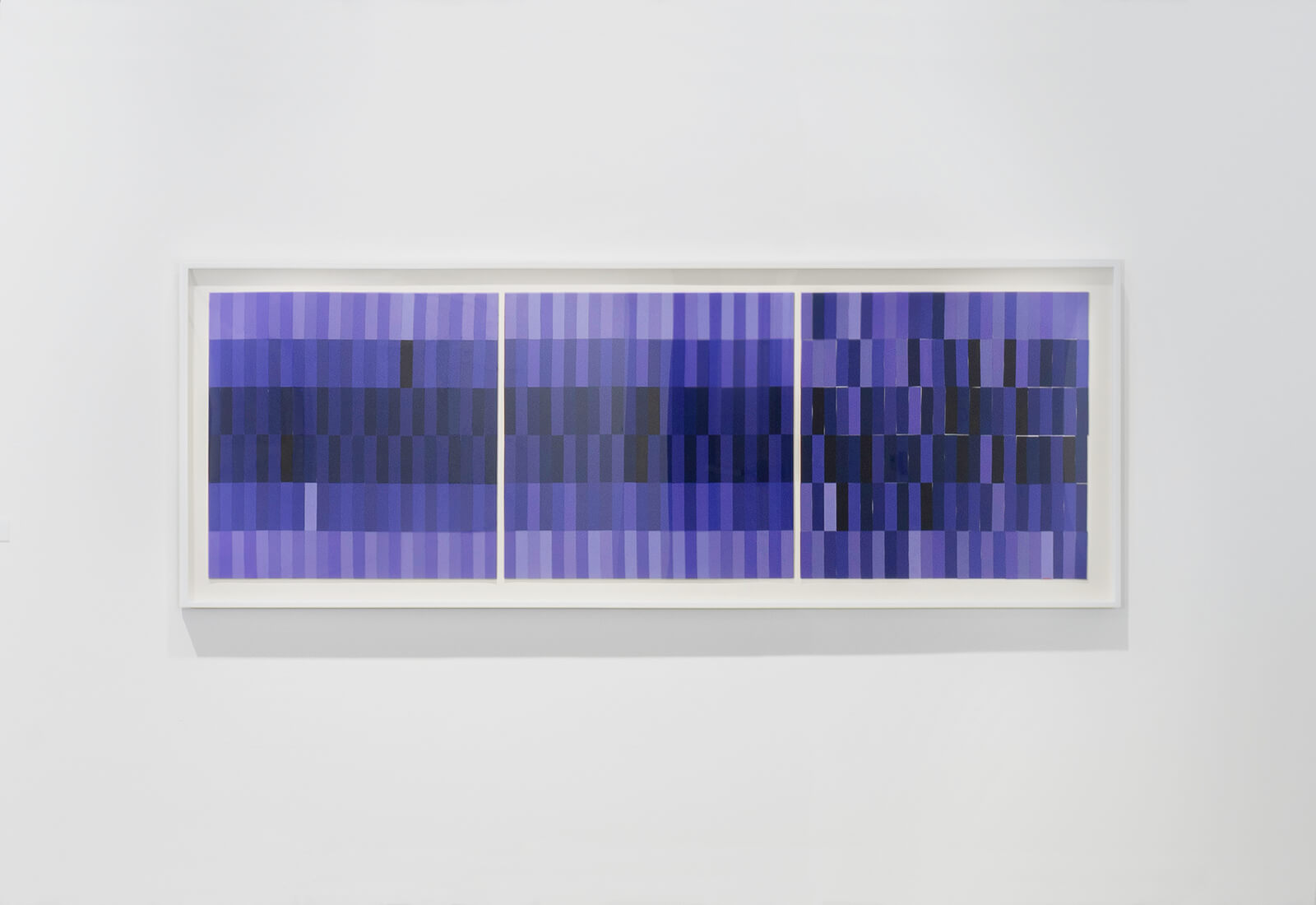

Vera Molnar, 144 Rectangles Triptych, 1969, gouache and cut paper collage on matboard, 23.5 x 70.5 in. / installation view: The Beall Center

for Art + Technology, Irvine, California (US) / Anne and Michael Spalter Digital Art Collection / photo: ofstudio

“The machine imaginaire algorithms used basic combinatorial mathematics, the area of math concerned with problems of selection, arrangement, and operation within a finite or discrete system.”

Before she had access to an electronic computer, Molnar worked with what she called the machine imaginaire, an imaginary computer or “a computer without a computer.”1 Molnar already knew what computers were, and what they could do, from books and magazines. While popular literature on computers focused on the looming question of artificial intelligence, the ‘electronic brain’ that might one day replace the human (a concern more rooted in science fiction than reality), what fascinated Molnar about computers was more practical than speculative or futuristic. It was their capacity to compute, and to do so accurately, quickly, and on a scale infinitely larger than a human could do alone. Perhaps what she found most appealing was how the computer crunched numbers and made decisions without the interference of what Molnar called “cultural ready-mades”—bias that might influence a human’s decision-making process. The idea was this: while an artist might make decisions according to principles of “good form” or “good composition” they learned in art school, the computer started with a clean slate, and could therefore make ‘objective’ decisions.

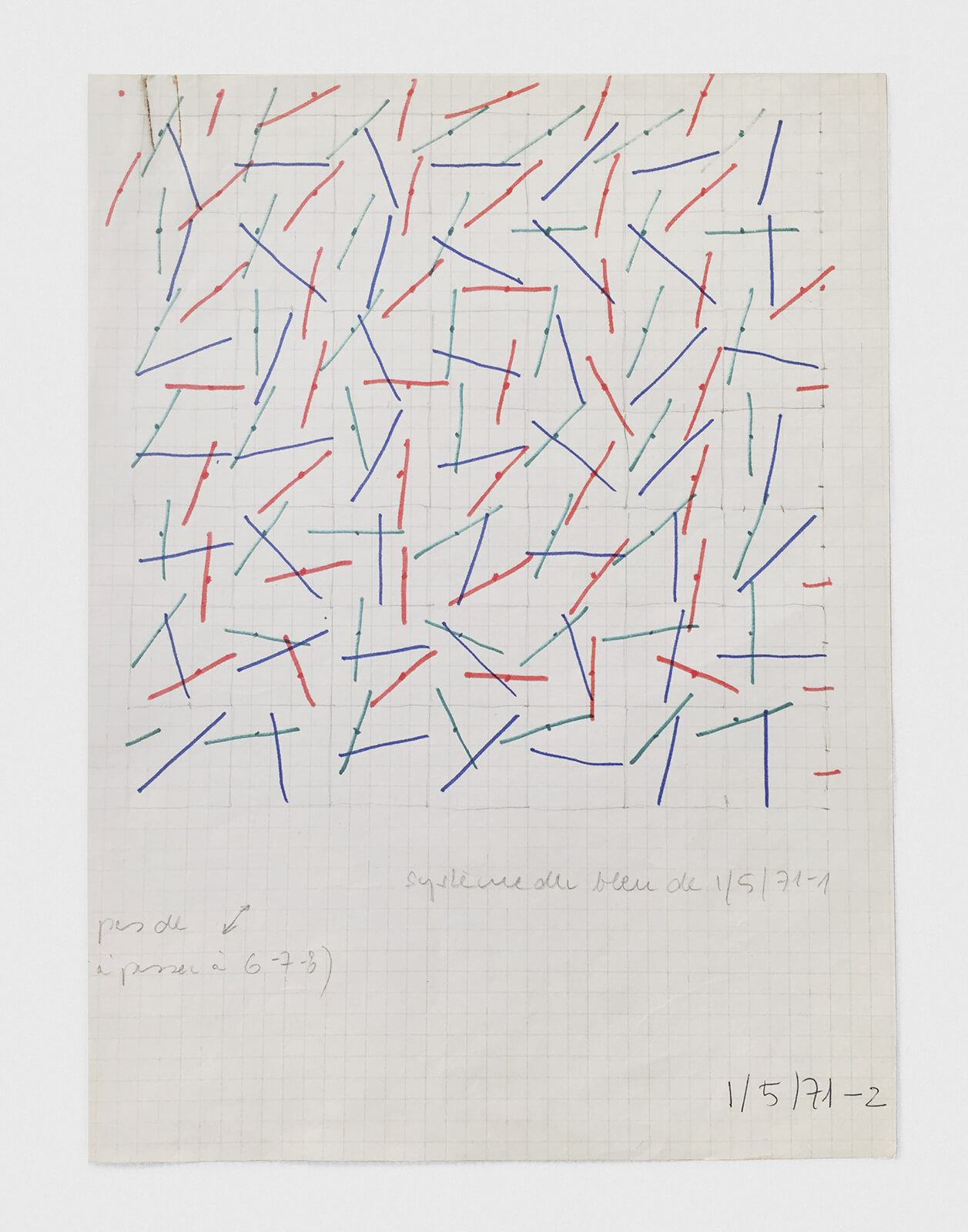

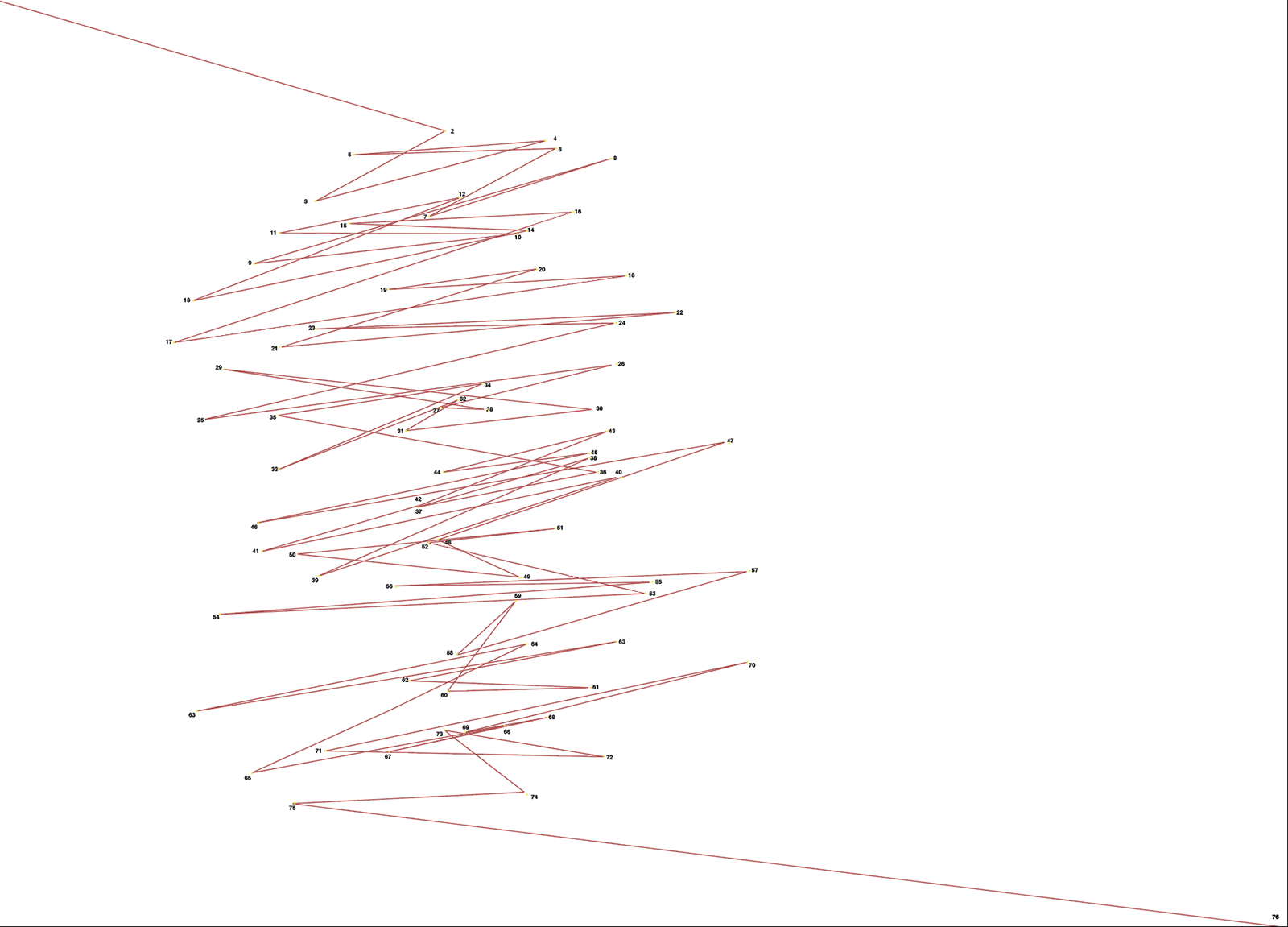

In the early 1960s, as the electronic computer remained expensive and out of reach, Molnar emulated its objectivity by hand-writing simple ‘programs’ to generate series of pictures. The machine imaginaire algorithms used basic combinatorial mathematics, the area of math concerned with problems of selection, arrangement, and operation within a finite or discrete system. Like a scientist conducting an experiment, she would alter only one variable or parameter in each iteration or variation, such as the choice of color or the angle of inclination of line segments. To make these changes, she often employed a rudimentary random-number generator: a roll of dice or the flip of a coin.

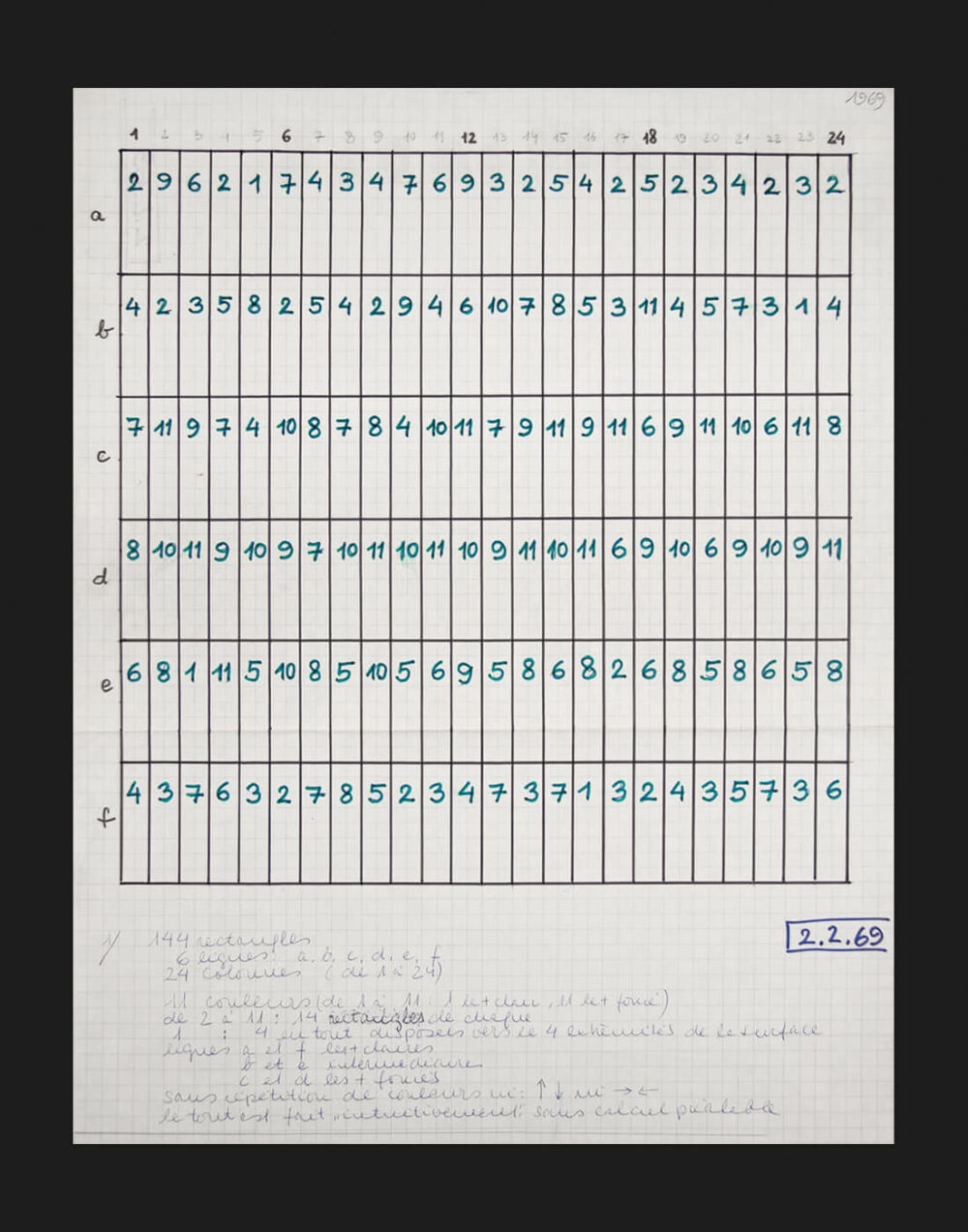

Vera Molnar, Untitled (Study for 144 Rectangles Triptych), 1969, felt tip marker, ink, and collage on graph paper, 13.5 x 10.5 in. / Anne and Michael Spalter Digital Art Collection

“Like a scientist conducting an experiment, she would alter only one variable or parameter in each iteration or variation.”

Molnar argues that her shift from machine imaginaire to machine réelle, in 1968, was not a radical break but rather a continuation of the same method with different tools. The digital computer, she wrote in Leonardo, was able to “facilitate the execution of this time-consuming procedure.”2 Using the computer was, put simply, more accurate and more efficient than executing programs by hand.

While 1968 is framed as such a pivotal moment in Molnar’s career, there are very few extant works from this period that bear visible traces of the computer. Skeptics might even say that her role as a pioneer of computer graphics has been exaggerated. Perhaps the reason Molnar’s earliest experiments are fuzzy to history is because we’re not looking for the right kind of evidence.

Let’s return to Molnar’s first encounter with the computer that I discussed in the context of her friendship with the composer Pierre Barbaud. On Barbaud’s invitation, Molnar visited the mainframe computer at Bull–General Electric in Paris. She went in wanting to experiment with random color distribution, but quickly found that they only had the hardware for monochrome graphics. So Molnar developed a program that generated a list of numbers (referred to as a listing in French), each corresponding to a color. Then, like a game of Paint By Numbers, she colored a grid of squares by hand according to these results. The image is not a plotter drawing; in its process, it is closer to the work of Jean-Claude Marquette, working across town in the other Groupe de l’art et informatique, who also used a listing to fill quadrille paper, which he then transposed to paint on canvas. Molnar, however, quickly tired of this method, and wouldn’t do it again. That was when she sought out the computer lab at Orsay, the Centre de calcul interrégional de calcul électronique (CIRCE), which had two different kinds of plotters; here, she could not only design pictures with computers but actually execute them computationally as well.3

Vera Molnar, 1 des premieres images d’après listing – BULL, mixed media, 29×29,5 cm, 1968 (DAM Berlin)

Molnar reminds us, however, that just because she started using a computer in the late 1960s doesn’t mean that she never made anything by hand again. It’s always been a back-and-forth for her—an idea that she crystalized in her recent artist’s book Main/Machine (Hand/Machine). David Familian, curator of the “Variations” exhibition, recently asked me about a triptych of collages in the show that Molnar made in 1969, 144 Rectangles. Did I know whether she used a computer here, or just a flip of a coin, to determine the placement of each purple rectangle? I shared Molnar’s anecdote about the listing—that some of her works, especially from this early period of computation, utilized the computer but were ultimately still handmade. It was a sort of “extension of the machine imaginaire,” David observed, “but instead of using a coin, she was using a computer.”

In other words, it would be reductive to divide Molnar’s work into pre- and post-computer art, with 1968 serving as a major turning point. The digital computer entered Molnar’s practice not with a bang, but gradually. We might even say that each step forward was followed by two steps back, until she figured out how the machine would best serve her interests. While Molnar has never presented herself as a ‘generative’ artist—this label is relatively recent, though not one she has explicitly rejected—the term feels especially appropriate here, for it acknowledges that an artist can work with systems and algorithms without necessarily using a particular technological tool. To focus on the generative is to focus on the artist’s process, which is what matters the most anyway.

“It would be reductive to divide Molnar’s work into pre- and post-computer art, with 1968 serving as a major turning point. The digital computer entered Molnar’s practice not with a bang, but gradually.”

References:

(1) Baby, Vincent. “Introduction à la « machine imaginaire » / Introduction to the ‘imaginary machine.’” In Vera Molnar: Pas froid aux yeux, edited by Vincent Baby and Francesca Franco. Paris: Bernard Chauveau Editeur, 2021.

(2) Molnar, Vera. “Toward Aesthetic Guidelines for Paintings with the Aid of a Computer.” Leonardo 8, no. 3 (1975): 185.

(3) Conversation with the author, Oct 10, 2021

Variations

Weaving VariationsExplore more of "Variations:"

→ HOLO.mg/stream/

→ HOLO.mg/vera-molnar-weaving-variations/