Variations: Media Archaeology

Research: Media Archaeology

“It’s a vein of media theory that sees history not as a linear, teleological progression of technologies but rather as nonlinear processes that leave behind material traces.”

“It’s a vein of media theory that sees history not as a linear, teleological progression of technologies but rather as nonlinear processes that leave behind material traces.”

“Rather than putting objects behind glass, media archaeological methods emphasize the process of making, especially when now-obsolete technologies were involved.”

Earlier this year, I moved to Berlin for eight months on a DAAD research fellowship. With Molnar based in Paris and hailing from Budapest, how did I end up in Germany on the last leg of my dissertation research trips? First, Molnar’s work has been collected and shown here more than in any other country outside of France. If you’ll forgive the cultural stereotype—Germans love squares. But the main draw of Berlin, for my research, was the Media Archaeological Fundus at Humboldt University, headed by Dr. Prof. Wolfgang Ernst. What is media archaeology?

Media archaeology is a vein of media studies that sees the history of media not as a linear, teleological progression of technologies but rather as a series of nonlinear processes that leave behind material traces. The ‘Berlin school’ of media archaeology, led by Ernst, has a special interest in studying media by actually using it. They are devoted to collecting obsolete technologies and making them operational again, thereby bringing them into the present. I was especially excited to work with Dr. Stefan Höltgen, who, until recently, ran the HU’s Signal Laboratory, a space devoted to resuscitating microcomputers, mainly from the 1980s. Here, I was fortunate to work with Stefan to re-program Molnar’s work on a machine she had actually used in the late 1970s, which allowed me to peer into the material world of early computer graphics and into her creative process, which is where I believe she made her biggest impact on twentieth-century abstraction and aesthetics.

“I was fortunate to work with Dr. Stefan Höltgen to re-program Molnar’s work on a machine she had actually used in the late 1970s, which allowed me to peer into the material world of early computer graphics and into her creative process.”

The work that we re-programmed or ‘re-enacted’ is Lettres de ma mère, a series Molnar worked on throughout the 1980s. In BASIC—the last programming language she would learn—Molnar wrote instructions to draw lines that mimicked her late mother’s distinctive, calligraphic handwriting. While they look like handwritten letters, they are entirely asemic or devoid of meaning. The work has incredible poetic potential, which Molnar, writing in Leonardo, tries to stifle by insisting that it’s purely a formal experiment, an investigation into composition. But whether she likes it or not, these images invite us to read between the lines, to wonder what the letters could have been about, to reconstruct an imaginary conversation between mother and daughter across the Iron Curtain. We could say that re-making Lettres de ma mère involves a reenactment of a reenactment: by tracing the lines of the plotter, I approximated Molnar’s marks, which in turn approximated her mother’s, preserved in the letters she sent her daughter after she left Hungary in 1947 til her mother’s death in 1971.

Vera Molnar, Lettres de ma mère, 1988, ink on plotter paper, 29,5 x 400 cm / collection: Musée de Grenoble

We focused on two versions of Lettres made in 1988 on long rolls of paper that unfurl like scrolls. Since the artist left very little documentation of her computational processes—at least not the kind of documentation that would be legible forty or fifty years later—re-programming Molnar’s work involves a fair amount of creativity and reverse engineering. No two approaches to reenactment produce the same results. In this case, the first step was incredibly analog: I had to buy a protractor and reach back into my ninth-grade geometry memory to remember how to measure angles. Stefan printed out a photograph of the first ‘letter’ and I traced the lines, counting the peaks and falls of the ‘handwriting’ and measuring the length of each mark. With this data, I was then able to start designing a computer program that could produce this kind of zigzagging line.

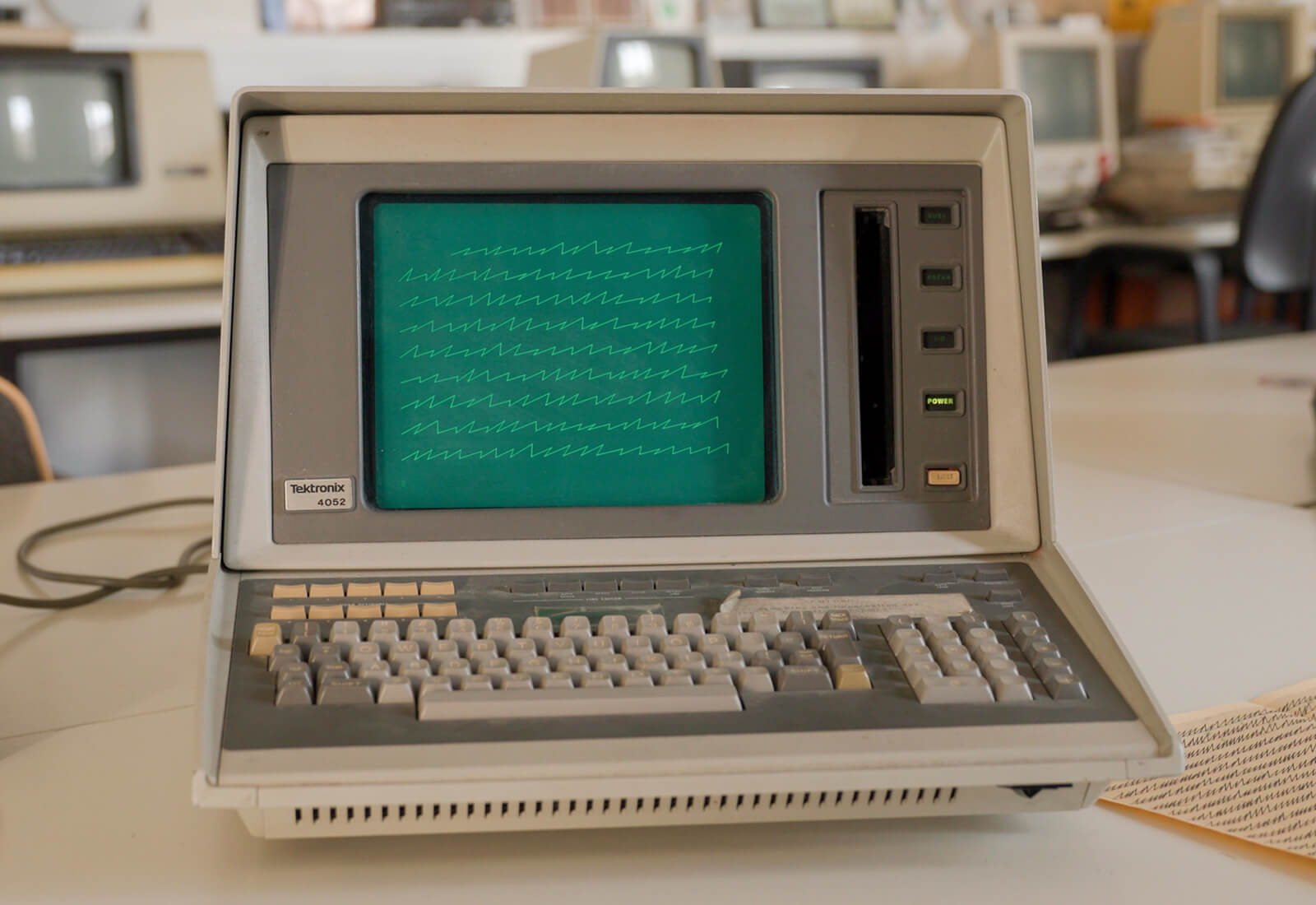

It was serendipitous that a collector of obsolete computers in Berlin happened to have a working Tektronix 4052, the microcomputer that Molnar would have worked on in the late 1970s at the Centre Pompidou’s computer lab, the Atelier de recherche des techniques avancées (ARTA). While this is not the machine Molnar used to make Lettres (that was an Apple II clone and later an IBM PC clone called the BFM), the point was not to show how some specific hardware determined the outcome of this artwork, but rather to explore Molnar’s general approach to programming graphics.

‘Drawing’ in BASIC is—excuse the pun—not so basic. It took me days to figure out something as deceptively simple as drawing a line. I reminded myself that, like me, Molnar was more or less an amateur when it came to computer graphics. If she could do it, so could I. It turned out that the Tektronix 4052 was better equipped for graphics than most microcomputers of its era. In fact, its built-in oscilloscope screen put its graphics capabilities front and center. While there is a functional Tektronix emulator online, being able to program the original computer—with its whirring fan and its clunky keys and its acid-green graphics that appear on screen like flashes of lightning—was an unparalleled experience that gave me a unique insight into Molnar’s process and into the early days of computer graphics more broadly.

“A collector of obsolete computers in Berlin happened to have a working Tektronix 4052, the microcomputer that Molnar would have worked on in the late 1970s at the Centre Pompidou’s computer lab.”

While art history tends to focus on objects that can be put behind glass or stored in drawers, incorporating media archaeological methods allows us to emphasize the process of making, especially when now-obsolete technologies were involved. By paying attention to these technologies and the material traces they left behind—often in the form of sketchy notes or ephemeral images—my aim is to shed light on the overlooked material history of early computer graphics, while also expanding our understanding of what constitutes a work of art, or an object of study in art history.

Variations

Weaving VariationsExplore more of "Variations:"

→ HOLO.mg/stream/

→ HOLO.mg/vera-molnar-weaving-variations/