Paste:

The

MUTEK

Recorder

Claire L. Evans ‘records’ the 2021 MUTEK Forum, sharing knowledge and research methods from selected guests.

The MUTEK Recorder is a real-time research experiment that captures, filters, and analyzes the 2021 MUTEK Forum through daily broadcasts and a sustained publishing sprint.

© 2021 HOLO

Claire L. Evans is a writer and musician based in Los Angeles. She is the singer and coauthor of the Grammy-nominated pop group YACHT, and the founding editor of Terraform, VICE‘s science-fiction vertical. She is also the former futures editor of Motherboard, and a contributor to VICE, Rhizome, The Guardian, and many other publications. Her 2018 book, Broad Band, tells the history of the female visionaries at the vanguard of technology and innovation.

When the visionary hypertext designer Ted Nelson was a young man, he took a job at the New York Times. One of his primary responsibilities at the paper was to refill the paste pots journalists used to cut and paste their stories together. Before the invention of the word processor, working writers often physically cut text into paragraph-sized chunks and rearranged them on tables to tease out interesting associations before ultimately deciding on a structure for their work.

“The words cut and paste, for writers, always meant taking your material, cutting it up, and putting it all around in front of you, in parallel, so you could see it side-by-side,” Nelson explained in a late ‘90s interview. This was the cut-up of the Dada poets and William S. Burroughs—an aleatory, sometimes radical juxtaposition of ideas—not the cut and paste of the computer, which Nelson condemns as an abomination.

When we ‘cut’ text in a word processor, it disappears to a clipboard, which holds it until it is ‘pasted’ elsewhere. Since the clipboard only holds one thing at a time, and remains hidden from view, a writer can only rearrange ideas in an extremely limited sense. Cut and paste, Nelson surmised, are “two holy words about human creativity,” and engineers, fundamentally misunderstanding them, desecrated the act of writing, creating an impoverished tool that reduces our ability to puzzle together complex ideas.

What we think is a consequence of the tools we use to think. Computers are tools for thinking, as are scissors and paste pots. This dossier, we hope, will be a tool for thinking too: a collage of insights, references, and thoughts that will accumulate as we simultaneously process and record our impressions of this year’s MUTEK Forum (Aug 24–Sep 2) in real time. Alongside the daily dossier, we’ll be broadcasting our findings live in an experimental variety half-hour mapping what we’ve learned from each day of the festival. To learn more about how others ‘record’ information, we’ll be joined by daily guests—artists, designers, musicians, and authors—who will share their tools for thinking and show us how they conduct research within their practice.

We’re not reporters, exactly; we’re recorders. But like journalists of another century, we will be speaking Nelson’s holy words, cutting, pasting, arranging and re-arranging, observing what connections we can make together, until something new begins to emerge from the noise. HOLO has invited me to refill the paste pots. Let’s see how the story comes together.

Based in Montréal and active through many international satellites, MUTEK is one of the world’s most storied electronic music festivals, having nurtured eclectic and experimental acts since 2000. Beyond their indefatigable promotion of new sounds and audiovisual performance, MUTEK’s flagship edition has always made space for critical conversations about all facets of digital art and culture. This year, we look forward to hearing from keynote speaker Benjamin Bratton, and artists Memo Akten, Sarah Friend, Ying Gao, Sabrina Ratté, and many others.

How does a sound artist translate their learnings into a new instrument design? What curiosities give life to a media artist’s installation? How do advocates leverage technology to nurture ethics and community? And which tools and methodologies do researchers, authors, and theorists use to organize information? To help us understand how different creative practitioners ‘record’ within their practice, HOLO invited eight multidisciplinary luminaries, one per MUTEK Recorder episode, to share glimpses into their research methods, data practice, central software, and media diet.

Tune into the daily MUTEK Recorder broadcast via the MUTEK website and follow this dossier for learnings, references, further readings from selected MUTEK Forum sessions.

Sound artist Yuri Suzuki works in installation and instrument design, and instruments like the synth he designed for Jeff Mills (2015) and his reimagination of the Electronium for the Barbican (2019) signal a deep reverence for electronic music. Over the last few years, London-based Suzuki became a partner at the international design studio Pentagram, where he has worked on branding projects for clients including Roland and the MIDI association.

Mindy Seu is a deep thinker about publishing, research, and archives, her recent projects include the much lauded Cyberfeminism Index, which compiled feminist provocations from Donna Haraway’s essay “A Cyborg Manifesto” through present day, providing an invaluable public resource. The New York-based designer is currently undertaking research stints with the MIT Media Lab Poetic Justice group and metaLab Harvard.

London-based Samaneh Moafi is a Senior Researcher at Forensic Architecture, a research agency investigating human rights violations and violence committed by states, police forces, militaries, and corporations. Moafi heads up the group’s Centre for Contemporary Nature, where she develops “new evidentiary techniques for environmental violence,” including analyses of environmental racism in Louisiana (2021) and the destruction of agricultural plots by Israeli forces at the edge of the Gaza Strip (2014-).

Dorothy R. Santos is the Executive Director of the Processing Foundation. Overseeing the foundation’s advocacy for software literacy in the visual arts, the San Francisco-based writer and curator has been integral in helping execute its mandate of increasing diversity in creative coding communities. In addition to her work for Processing, Santos is a co-founder of the REFRESH curatorial collective, which emerged in 2019 with a focus on inclusivity and promoting ”sustainable artistic and curatorial practices.”

Writer and designer Xiaowei R. Wang is driven by beliefs in the “political power of being present, in dissolving the universal and categorical.” They are the Creative Director of Logic, and author of Blockchain Chicken Farm, a book that looks to rural China—not their homefront Silicon Valley—as a locus of tech-innovation. Wang’s recent artistic works include Future of Memory (2019-), an exploration of language and algorithmic censorship, and Shanzhai Secrets (2019), which explores consumption and copyright by way of Shenzhen.

Making his mark on digital art over the last two decades, Jürg Lehni has mobilized Hektor, Rita, and Viktor, a series (2002-) of quirky drawing machines, as platforms for research on representation and histories of technology. Parallel to his robotic storytelling, the Zurich-based artist and designer has made open software for others, including the prescient Adobe Illustrator plug-in Scriptographer (2001-12), that pushed the graphic design tool towards more open-ended experimentation, and, more recently, the browser-based “Swiss Army knife of vector graphics” Paper.js (2011-).

Hailing from the UK and now based in Ottawa, Tim Maughan traces the contours of contemporary phenomena including logistics and complexity as a journalist and technology pundit, which informs his science fiction. His first novel Infinite Detail (2019) wryly imagined a post-internet future (and related calamities). In addition to that debut, which was heralded as a Sci-Fi book of the year by The Guardian, he has written screenplays for the experimental short films Where the City Can’t See (2019) and In Robot Skies (2018), both directed by Liam Young.

Benjamin Bratton is Professor of visual arts at UCSD in San Diego, and author of The Stack (2016) and The Revenge of the Real (2021), which, respectively, schematize systems of scale and governance after Big Tech, and consider what politics in a post-pandemic world could be. Bratton is also the Program Director for The Terraforming, a multi-year initiative at Moscow’s Strelka Institute that tasks design students with taclking the radical transformations required for Earth to remain a viable host for life as we know it.

Keynote

Benjamin Bratton

Orit Halpern

Benjamin Bratton

Benjamin Bratton is Professor of visual arts at UCSD in San Diego, and author of The Stack (2016) and The Revenge of the Real (2021), which, respectively, schematize systems of scale and governance after Big Tech, and consider what politics in a post-pandemic world could be. Bratton is also the Program Director for The Terraforming, an initiative at Moscow’s Strelka Institute that tasks design students with tackling the radical transformations required for Earth to remain a viable host for life.Bratton opens by locating the history of technology as also being a history of thought. Noting the true product created by philosophers of technology (like the recently passed Jean-Luc Nancy) is that grappling with the implication of new technologies reveals new facets of how we already think, and how we might think in the future.

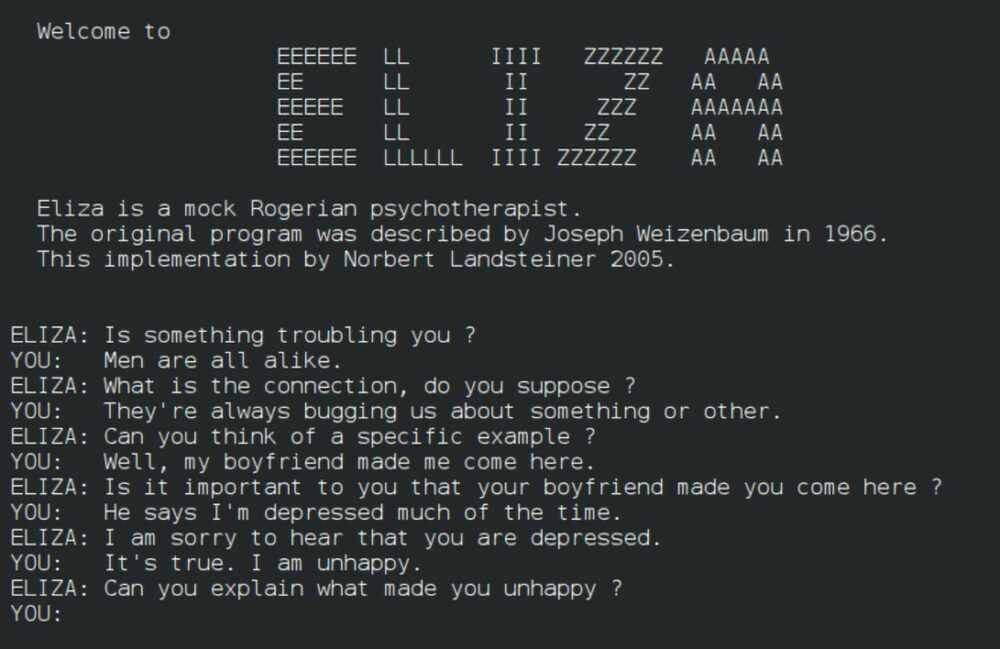

Recent AI systems move beyond the clumsiness of early chatbots like ELIZA. Their ability to understand and respond to semantics and engage in wordplay—actions we’d normally associate with intelligence—suggest we’ve crossed a threshold where artificial systems can absorb knowledge. We’ve been stuck in a loop for a while with our discourse about these systems though: we erroneously confuse their competency for comprehension.

The ‘Artificial’ in artificial intelligence is located in the artifact, in material culture. Example: an arrowhead reveals an intentionality towards the natural world.

“We’re using our distributed computer power to distribute 4K video on TikTok when we could be dedicating those resources to sophisticated natural language processing.”

Orit Halpern

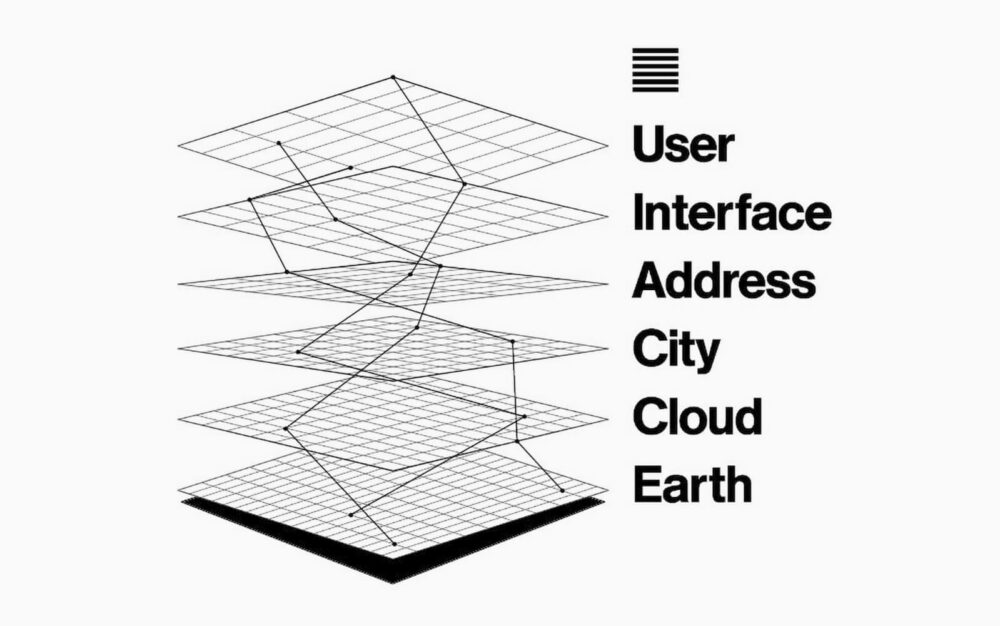

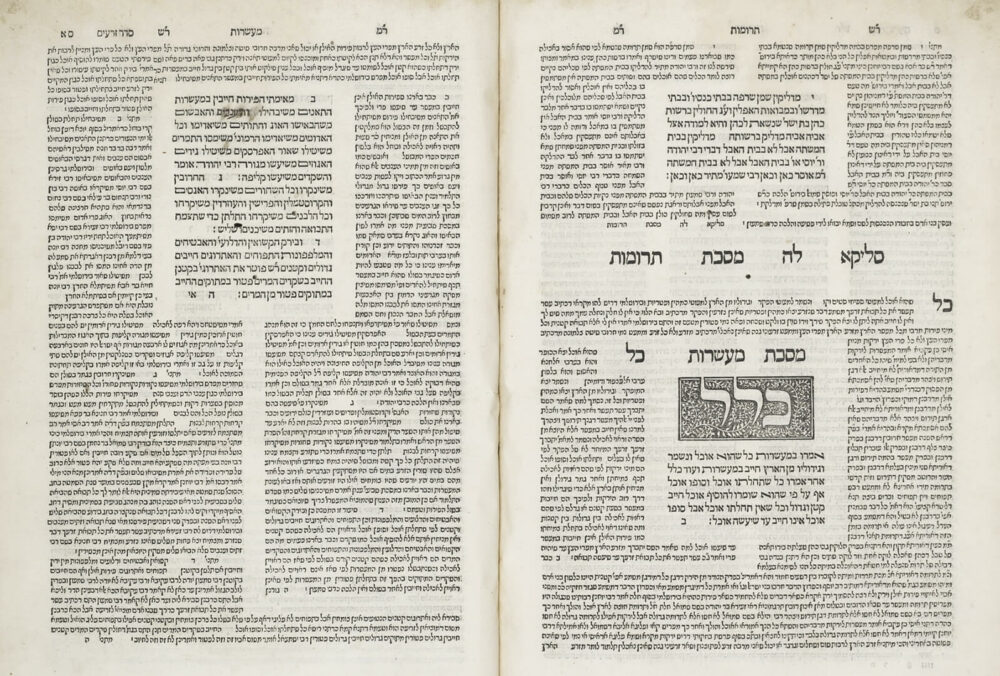

Orit Halpern is an associate professor at Concordia University in Montréal, working within the Speculative Life cluster within the Milieux Institute. Her work bridges histories of science, computing, and cybernetics, and she is the author of Beautiful Data (2015).Stack diagram by Metahaven.

‘Data’ and ’waste’ are problematic qualifiers for thinking about what gets generated by technological systems. The distinctions are not as clear-cut as we might think are and often what we label as one, might actually be the other.

We’ve been overly “blunt” in how we use the word ‘surveillance,’ and focused on its negative connotations. A more useful term is ‘sensing layer’ whereby that monitoring is mobilized for governance. In the popular vernacular about surveillance there is a concern about individuals being seen, watched, and compromised, but there are just as many cases of communities and bodies not being seen or tended to (e.g. the many demographics that have become invisible during the pandemic). We’ve been collecting the wrong data—habits of consumption—and it does not help conceive or implement needed positive social change. Climate science is a key example of the kind of datasets and archives we should be building—and acting on.

• Richard Brautigan, “All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace” (1969)

• Anastasia Sinitsyna et al, “Face As Infrastructure” (2020)

Bratton’s framing of the artificial vs. the synthetic, and the statement early in his keynote that “no one single neuro-anatomical disposition has a privileged monopoly on how to think intelligently” echoes some of my own recent research into unconventional computing and Artificial Life, a discipline in computer science concerned with building life, or intelligence, from the bottom up, rather than from the top down. ALife researchers see life as a property of form, not matter—a perspective Bratton evidently shares! The computer scientist Christopher Langton writes about life as a dynamic, non-linear system, which emerges from the interactions between parts. Using an analytic method to examine life’s constituent parts in isolation makes no sense, because we lose those critical interactions that define life. It’s more generative to take a synthetic approach, examining life’s constituent parts in each others’ presence—and even to build instances of those constituent parts in silico. “Rather than take living things apart,” Langton writes, “Artificial Life attempts to put living things together.”

Panel

Eliane Ellbogen, Elena Zavelev, Cadie Desbiens-Desmeules, Ryan Stec, Joseph Cutts

Eliane Ellbogen

Eliane Ellbogen is an intellectual property lawyer with business law firm Fasken, and focused on information technology. She advises and represents clients in complex, high-profile patent, trademark, copyright and trade secret mattersIn this boom phase, NFTs prompt far more questions than answers. The lack of standardization around copyright and the durability of the work are thorny issues for both artists and buyers alike. We’re truly making up the rules as we go, thus far.

Image: Hic et Nunc profile of AI artist Mario Klingemann

“How can we leverage NFTs but not reproduce the same power structures that already exist and without widening the gap between those that succeed and those that don’t?”

Elena Zavelev makes a great point about the role of community in the NFT marketplace. To me this is most novel aspect of crypto-art: artists are collecting one another left and right, at a scale and with a vocal enthusiasm you just don’t see in the traditional art marketplace, which is too financially prohibitive for the kinds of smaller-scale, armchair collectors that are the lifeblood of the NFT markets. On Hic et Nunc, for example, artists regularly sell inexpensive editions, which makes owning their work accessible to a much broader group of people. I’ve written about how these inexpensive editions—and the relative exchange rate of cryptocurrencies around the world, relative to the cost of living—has opened up new economic realities for artists in the Global South. There are massive crypto-art scenes in Brazil, Malaysia, Turkey, and the Philippines. I find that extraordinarily exciting.

The MUTEK Recorder

Claire L. Evans

Yuri Suzuki

Yuri Suzuki

Sound artist Yuri Suzuki works in installation and instrument design and is best known for the synth he designed for Jeff Mills (2015) and his reimagination of the Electronium for the Barbican (2019). More recently, London-based Suzuki became a partner at the international design studio Pentagram, where he has worked on branding projects for clients including Roland and the MIDI association.

EZ Record Maker

The antithesis of our current Spotify moment, EZ Record Maker is a joint-venture by Suzuki and Japanese publisher Gakken that endeavours to bring low cost vinyl record creation to the masses. With a dead simple interface, users simply plays audio through the an auxillary cable or USB and then lifts the cutting arm onto a blank disc—and voila, EZ record, made.Conversation

Sabrina Calvo

sava saheli singh

Sabrina Calvo

Sabrina Calvo is a transdisciplinary artist who has spent twenty years deconstructing narratives and designing virtual worlds. Calvo is the author of the novels Toxoplasma (2016) and Melmoth Furieux (2021). She rediscovered sewing in 2020, a practice allowing her to build “an intimate poetry between clothing and magic.”

Reve Riviere

Calvo rediscovered sewing in 2020 and her designs are brimming with cuts, tears, strings, and sashes. See her Instagram account @reve.riviere, where she dutifully logs impressionistic sketches, material samples, and the glorious mess of her sewing table.Having worked across fiction, performance, and fashion Calvo points to two common themes that fuel her work. The first is being attuned to dreams and “trying to manifest them” irregardless of medium or material. Secondly, a deep empathy, informed by introspection about what one can offer, and listening closely for what others need.

Queer and marginalized creators have an opportunity to help others with their stories, by representing alterity and other ways of being, and also by combatting the “monpolization” of spirituality by non-inclusive actors.

How to nurture a radical, inclusive, art-making practice that is not driven by profit. Stay focused on work you love while learning your craft very well, then, outsource your technical skills. Channel that revenue back to your art and keep your practice pure.

sava saheli singh

sava saheli singh is the eQuality-Scotiabank Postdoctoral Fellow in AI and Surveillance at the University of Ottawa AI + Society Initiative. In a previous post-doc at Kingston University singh co-produced three experimental short films as part of the Screening Surveillance series, and she is currently researching how teachers use learning technologies in their practice and how this has been impacted by COVID-19.“Fashion is just being draped in dreams, basically. Dreams are manifest, with us every day, and a form in themself.”

Toxoplasma

Calvo’s 2016 science fiction novel takes place after the revolution. In it the island of Montréal is under siege—its bridges are blocked by the federal army. Supporters of the old liberal world and those who aspire to an anarchist society are tearing the streets up, seizing the moment and transforming the cityscape into something new, in which human communities survive and reconfigure themselves.

Calvo has an expansive practice, spanning writing, game design, and textile work. I loved her graceful way of talking about both the immaterial and the material aspects of art-making, and the “beautiful correlations” she discovers while working across mediums. The practice of sewing by hand, for example, drew her back to writing by hand, after she realized how much of writing passes through gesture. What emerges from the pen is so much different than what emerges from the keyboard, I think because the tip of a pen on paper is a single point of focus, a direct line from the mind through the body and onto the page. Typing, on the other hand, requires a forking of focus: the eyes land in one place, the screen, while the hands are off doing their own thing. Calvo talked about dreams, about the project of making dreams manifest. I think that requires a certain fluid, frictionless relation between body and mind.

Panel

Lukas Volz, Grand River, Richard Chartier, John Connell

Lukas Volz

Lukas Volz is a neurologist and head of the Network Plasticity Lab at the University of Cologne, where he investigates neural plasticity and the reorganization of human brain networks using neurostimulation and neuroimaging. Lukas undertook graduate studies at the Ruhr-University in Germany and was a postdoctoral scholar at the Max-Planck-Institute for Neurological Research and UC Santa Barbara.The relationship between meditation—focused breathing—and wellness is well documented but the recent ‘mindfulness turn’ has seen a wider public interested in sharpening their attention. Musicians have a place in this conversation and by treating sound as an object (rather than commodity) we might further mold our capacity to listen and be present.

Grand River

Aimée Portiolia is a Dutch-Italian composer and sound designer who records and performs as Grand River. Influenced by classical minimal music, her debut album Crescente was released in 2017 on Spazio Disponibile and her sophomore album Blink A Few Times To Clear Your Eyes was released on Editions Mego in 2020.

Richard Chartier

Richard Chartier is a Los Angeles-based artist and composer. His works explore the inter-relationships between the spatial nature of sound, silence, focus, perception, and the act of listening itself. Chartier has released music on labels including Room40, Editions Mego, and his own imprint LINE. Beyond composition, he has collaborated on installations with artists including Evelina Domnitch & Dmitry Gelfand, and Linn Meyers.

The mindfulness conversation entered brain-bending territory when the neuroscientist Dr. Lukas Volz pointed out that our brains construct an internal model of the world that constantly predicts what will happen next—which means that what we experience in any given moment is not what is actually happening around us. Rather, our brains constantly create their own subjective illusion of reality, which then effectively becomes our reality. How can we gain access to this internal model and improve it, so that we can in turn improve our lives? Dr. Volz suggests that sound is a way in—and that music, with its repetitive patterns and rhythms, might in fact tickle the internal model’s predictive mechanism. I found this unexpected relationship between perception, sound, and time fascinating. It lends a measure of scientific rigor to the promises of mindfulness, of course, but it also explains the primal appeal of music, more generally.

Q&A

Sarah Friend

Charlie Robin Jones

Sarah Friend

Sarah Friend is an artist and software developer who engages software as a site-specific media, systems as speculative fictions, and worldbuilding as praxis. She is a participant in the Berlin Program for Artists, a co-curator of Ender Gallery, an artist residency taking place inside the game Minecraft, an alumni of Recurse Centre, and an organiser of Our Networks, a conference on all aspects of the distributed web.The crypto world is awash in protocols that have for better and worse given us many new forms to make sense of. Friend’s body of work is a sustained critique of these new typologies and lays bare how these new mechanics of generating wealth and ascribing value work. Rather than take this new vernacular—mining, minting, owning—for granted, we need to interrogate these new ways of relating and interacting.

Charlie Robin Jones

Charlie Robin Jones is the head of external relations for the cultural strategy group Flamingo, editor-at-large of materialist journal Real Review and UK correspondent of Flash Art, where he writes a quarterly column on fashion.• Dean Kissick, “The Downward Spiral” Spike (A vital takedown of the aspects of NFT consumption much of Friend’s work critiques)

• Remembering Network (Sarah Friend’s digital “seed vault” for threatened and extinct species)

The MUTEK Recorder

Claire L. Evans

Mindy Seu

Mindy Seu

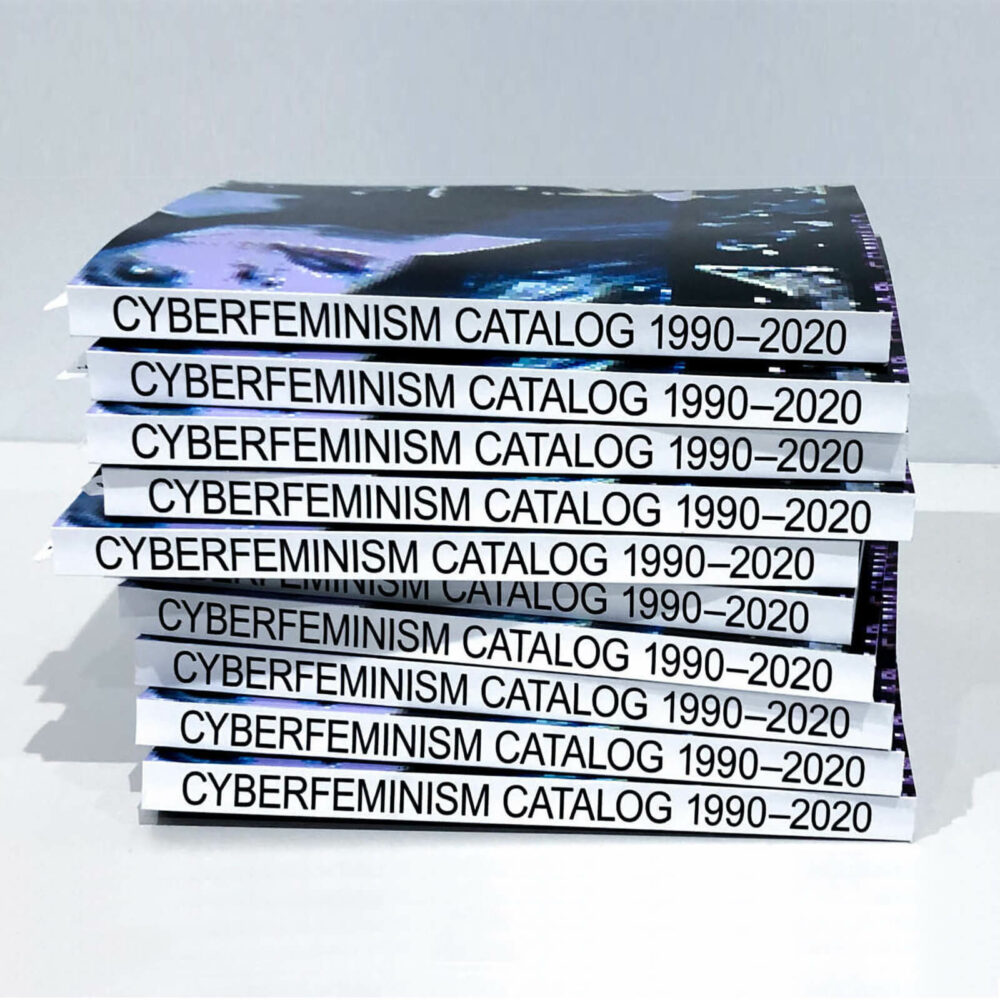

Mindy Seu is a deep thinker about publishing, research, and archives, her recent projects include the much lauded Cyberfeminism Index, which compiled feminist provocations from Donna Haraway’s essay “A Cyborg Manifesto” through present day, providing an invaluable public resource. The New York-based designer is currently undertaking research stints with the MIT Media Lab Poetic Justice group and metaLab Harvard.

Cyberfeminism Catalog

The precursor to Cyberfeminism Index, Cyberfeminism Catalog was Seu‘s 2019 thesis project at the Harvard Graduate School of Design. Much of the legwork for the index was done here, and Seu collected, collated, and ruminated on the origins of 1980s and ’90s origins of cyberfeminism, ”pushing it into plain sight for others to respond and build upon,” in print before HTML.Conversation

Matthew Herbert

Love Ssega

Matthew Herbert

Matthew Herbert is a composer, producer, and writer who has recorded more than 30 albums. These include the much-celebrated Bodily Functions, a score for the Oscar-winning film A Fantastic Woman, and music for the National Theatre. Herbert has performed solo, as a DJ, and with various musicians including his own 21-piece big band and 100-piece choir—from the Sydney Opera House to the Hollywood Bowl—and created installations, plays, and operas.The music industry is having a real stocktaking about its environmental impact at the moment. While physical media is passé, the streaming economy is hardly immaterial—Spotify ranks alongside YouTube in its emissions. Musicians that choose to minimize their impact on the environment have difficult decisions to make. While the prospect of economic sacrifice is daunting, it can be received positively: as an opportunity to rethink how musicians release, distribute, and perform.

We need more punk! Many genres ripple with subversive energy, music—as a force—has histories and tactics it can draw on to make noise that is loud enough to capture the public’s imagination.

It’s naive to put cultural production outside capitalism, and if musicians are scoring the soundtrack of advertisements promoting wasteful products and services, they are part of the problem not part of the solution.

Love Ssega

Love Ssega is a British-Ugandan artist and producer from London, UK. He was a founder member of Grammy Award-winning band Clean Bandit and has a PhD in Laser Spectroscopy from Cambridge University. As a solo artist he has toured globally and been the Musician in Residence of China for the British Council and PRS Foundation. He was also recently commissioned for a national year-long artistic response to the climate action, celebrating underrepresented voices.“Who are we waiting for? Another Ghandi? Is that who it will take to stop us from shopping and travelling ourselves to death?”

It strikes me that the conversation about sustainability and music reached a kind of critical mass earlier this year, in tandem with what Sarah Friend yesterday referred to as the “JPEG summer” of NFT hype. During that initial upwelling of interest in crypto-art, audiences, collectors, and critics alike were actively measuring the carbon footprint of individual artworks using calculators like CryptoArt.wtf—a tool that was eventually retired after it was being used to harass and abuse artists in this space. A consequence of those heated conversations, however, was a larger reckoning about the carbon footprint of so many other things artists take for granted as being part of the the cost of doing business: touring worldwide in gas-guzzling airplanes, buses, and cars, the detrimental ecological effects of printing and shipping merchandise, and what it takes to have every song in the world available for streaming on a moments’ notice. Ultimately it seems there is no 100% environmentally sustainable way to build an economically sustainable career.

Panel

Analucia Roeder, Sol Rezza, Gabrielle HB, Amanda Guiterrez

Gabrielle HB

Gabrielle HB is a sound artist working between the unceded territories of Nitaskinan and Tiohtià:ke, known as Lanaudière and Montreal. She uses voice, words, synthesisers and field recording to generate works, oscillating between free improvisation and slow composition. Her album Playing the Daily Scores was presented during the 2020 edition of Suoni per il Popolo festival and she is a member of Le désert mauve and Jardin.The empathy and respect implicit in consent culture could easily be extended to sound. As digital art and music lovers we’ve gone to one or two shows that were just unbearably loud—and experienced the ringing in our ears hours or days later. In hindsight, isn’t that discomfort, to say nothing of the permanent hearing damage, a violation?

Embodiment and immersion are ubiquitous ideas that we all understand. We desire stimulation and expect it from our digital media. However, perhaps we need to step back from this consumptive mindset and think about the types of experience we want and need, versus always default to the spectacular.

The influence of AI is pronounced on many aspects of culture, but relative to listening it’s a bit more subtle in its influence. If algorithms are now tasked with aspects of mixing and mastering; compressing frequencies to conserve bandwidth; and building our custom-tailored playlists based on mood, previous activity, and demographics, they’re tangibly changing how we listen and what we hear, as well as picking the soundtrack to our lives.

Amanda Guiterrez

Amanda Gutiérrez is a Ph.D. student at Concordia University who uses a range of media, such as sound and performance art, to investigate the aural culture of everyday life. Gutierrez is actively advocating for listening practices while being one of the board of directors of the World Listening Project and serving on the scientific comitée of the Red Ecología Acústica México.

Analucia Roeder

Analucia Roeder is a Lima-based multimedia artist working across documentary, live visuals, generative art, and VR. Currently part of MUTEK’s AMPLIFY D.A. cohort, her 2016 documentary Cocachauca (2016) was awarded Most Innovative Film at Argentina’s CINECIEN and she premiered her first solo VR experience, Inside A at London’s Sommerset House Studios.

Sol Rezza

Sol Rezza is an Argentinean composer and sound designer fusing experimental electronics with immersive audio. A specialist in audio spatialization and digital storytelling, she develops her work in virtual environments and live performances moving between art, psychoacoustics, and technology. Her work has been featured at festivals including CTM Festival & Deutschlandradio Kultur (DE), MUTEK (CA), and File Prix Lux Festival (BR).

Recently I went to a NASCAR race. I’ve never experienced such a sonic assault; the dull roaring drone of twenty high-powered cars tearing across a concave circuit was physically obliterating. Volume is everywhere. In many situations, it’s beyond our control. As artists, we have the responsibility to use volume mindfully. Sonic intensity is common, but sonic intensity with purpose, deployed conscientiously, with clear markers so that audiences can consent to entering into the experience, is rare.

I appreciated Gabrielle HB’s call to explore a diversity of intensity in electronic music. Our culture seems to take loudness as a default—she referred to it as a “culture of loudness.” Perhaps it’s easy to be loud. It’s shorthand for power. It’s like in visual art—bigger paintings sell. There’s something about presence that captures the market’s imagination, that sweeps audiences away. It’s more difficult to be subtle. Perhaps the pandemic, the kind of interiority that the pandemic has sparked in us collectively, will reveal a more diffuse, quiet, and nuanced end of the sonic spectrum.

The MUTEK Recorder

Claire L. Evans

Samaneh Moafi

Samaneh Moafi

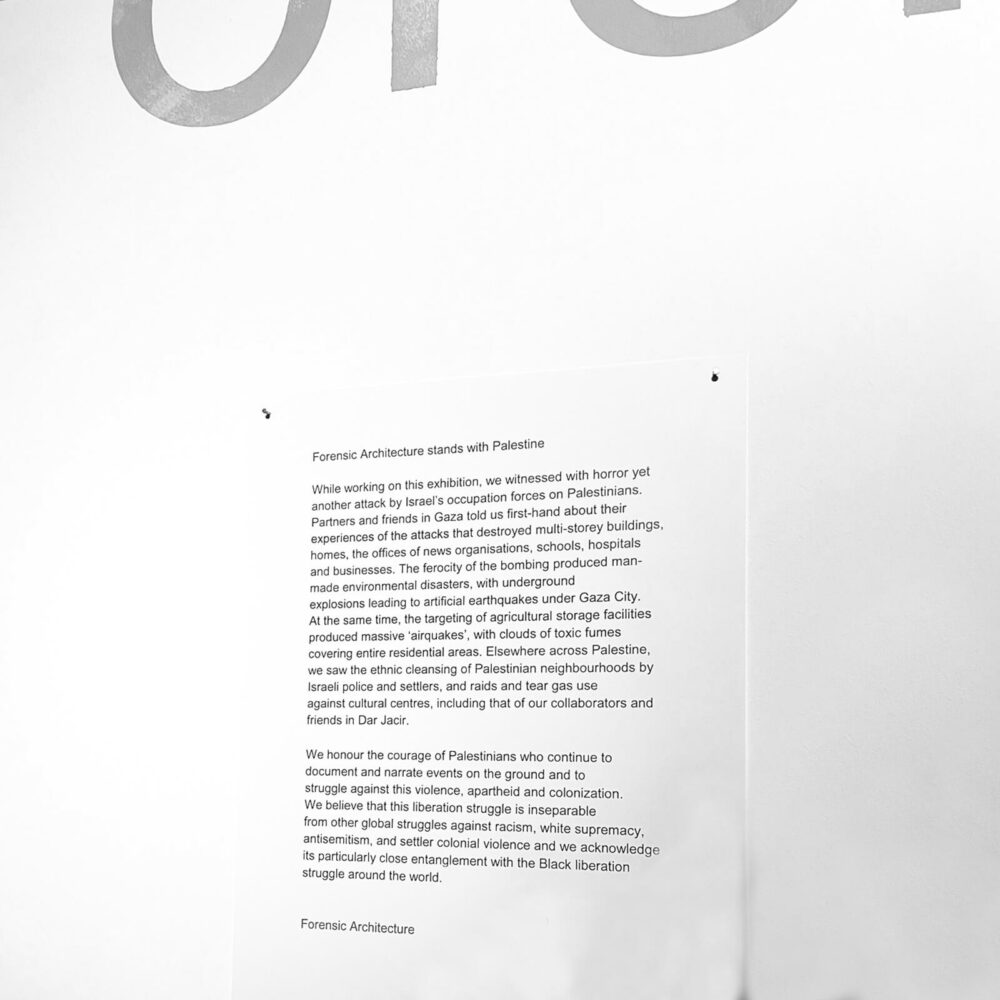

Samaneh Moafi is a Senior Researcher at Forensic Architecture, a London-based research agency investigating human rights violations and violence committed by states, police forces, militaries, and corporations. As head of the group’s Centre for Contemporary Nature, she develops “new evidentiary techniques for environmental violence,” including analyses of environmental racism in Louisiana (2021) and the destruction of agricultural plots at the edge of the Gaza Strip (2014-).

Conversation

Ryan Howard

Tina Blakeney

Ryan Howard

Ryan Howard leads a global portfolio of experiential programs at Google with a focus on enabling experiences at enterprise scale. Previously, he led similar programs at Goldman Sachs and worked as a design and engineering consultant spanning a wide range of creative technology applications.

Tina Blakeney

Tina Blakeney is a Director of Production in the Thinkwell Group’s Montréal Studio, where she draws on her background in the creative and digital industries, themed environments, immersive experience design, video production, and post production. Blakeney is an experimental filmmaker, photographer and VJ, working with 8mm and 16mm film for live performances and installations.Tech companies like Google find themselves in a (fairly) unique position of designing products and experiences for individual users and billion-plus audiences. This unprecedented scale has prompted considerable internal soul searching about guidelines for accessibility and flexibility.

Contemporary users expect emotional engagement, not just functionality or rich user experiences. This spans software and space and the expectations about these two realms are not mutually exclusive.

This might be tangential, but I wanted to share an anecdote: when I was writing my book, Broad Band, I profiled a group of women who built one of the earliest online services targeted explicitly to women, a First-Class BBS community called Women’s Wire, which became women.com in the early ‘90s. There was a tension within the Women’s Wire group that occurred at a key moment between the era of dial-up services, listservs, and message boards and the dawn of the World Wide Web. Basically, they couldn’t agree what the internet was for. Was it an information resource—a place where people went to get weather reports and stock updates—or was it an exchange—a place people went to share their experiences with others? Choosing one side, at the time, seemed vital to building a coherent business. One member of the team, however, told me something that I think is very wise. “At a certain level of intensity in an either/or argument,” she said, “the fact that it has reached that intensity is the indicator that the right answer is and.” When we’re talking about bridging between screens, and between meatspace and cyberspace, we should keep that in mind: we’re long past “either/or.” The answer is always “and.” And is fertile. We’re inhabiting a great big “and” right now, with this Forum, which exists everywhere and nowhere at once.

Panel

Isabella Salas, Yuri Suzuki, Maya Indira Ganesh, Ali Nikrang

Isabella Salas

Born and raised in Mexico City, Isabella Salas’ interdisciplinary artworks use artificial intelligence, video, synthesized sound, video projection as medium to create multisensorial digital experiences based on neuroaesthetics design. Her work has been presented in digital art institutions including the Societe des Arts et Technologies, MUTEK AI Lab, Gamma XR Lab, TransArt Festival.

Maya Indira Ganesh

Maya Indira Ganesh is a tech and digital cultures theorist. Her dissertation research examined the political-economic, social, and cultural dimensions of how the ‘ethical’ is being shaped in data-field worlds, rich in histories and imaginaries, of AI and autonomous technologies. Prior to this, she worked at the intersection of gender justice, digital activism, and international development.Because we can’t define creativity precisely, attempts to categorize algorithmically produced work as ‘creative’ or ‘not creative’ are futile. The discussants all sidestepped a question to this effect and they instead seemed more interested in clarifying how AI helped their process than judging the authenticity of what (or how) their machines produced.

Intentionality is just as thorny as ‘creativity,’ and using that as a lens for analyzing automation prompts a few interesting questions. First, to what degree can an artist or creator erase themselves from a process they set in motion? Second, how have automation’s failures—glitches, crashes—impacted our aesthetics?

Yuri Suzuki

Sound artist Yuri Suzuki works in installation and instrument design and is best known for the synth he designed for Jeff Mills (2015) and his reimagination of the Electronium for the Barbican (2019). More recently, London-based Suzuki became a partner at the international design studio Pentagram, where he has worked on branding projects for clients including Roland and the MIDI association.

Ali Nikrang

Ali Nikrang is a key researcher and artist at the Ars Electronica Futurelab in Linz, Austria. His background is in both technology and art, and his research centers around the interaction between human and AI systems for creative tasks, with a focus on music. He is the creator of the software Ricercar, an AI-based collaborative music composition system for classical music.

So much of the discourse around AI and art recently framed the AI itself as an agent of creativity, rather than as a tool through which artists can explore and expand their own perceptions or abilities. I’m all for the thought experiment of trying to appreciate the output of an AI on its own merit—maybe it even helps us to decenter the human perspective—but if I’ve learned anything from my own work researching the history of computation, it’s that we have an almost uncanny ability to gloss over the human in the loop in favor of a good story. And that always causes harm. The very first time the press reported about the ENIAC, the first programmable electronic computer, after it was declassified at the end of the Second World War, they were so seduced by the idea of a giant electronic brain that they completely ignored the fact that the “giant electronic brain” was useless without the teams of programmers who spent weeks setting up problems and physically feeding them, byte by byte, into the machine. We are not doing much better with AI today: a notion lingers that technology is neutral, autonomous, and infallible. What a drag. Artists have an enormous role to play here, both in pushing the technology forward and being very clear about the labor, thought, and intention surrounding work produced with the assistance of AI or machine learning techniques. As Maya Indira Ganesh said during this conversation, there’s always a shadow human in the loop. Where and who are they? What is their intention? What are they trying to say, using this technology as a conduit?

The MUTEK Recorder

Claire L. Evans

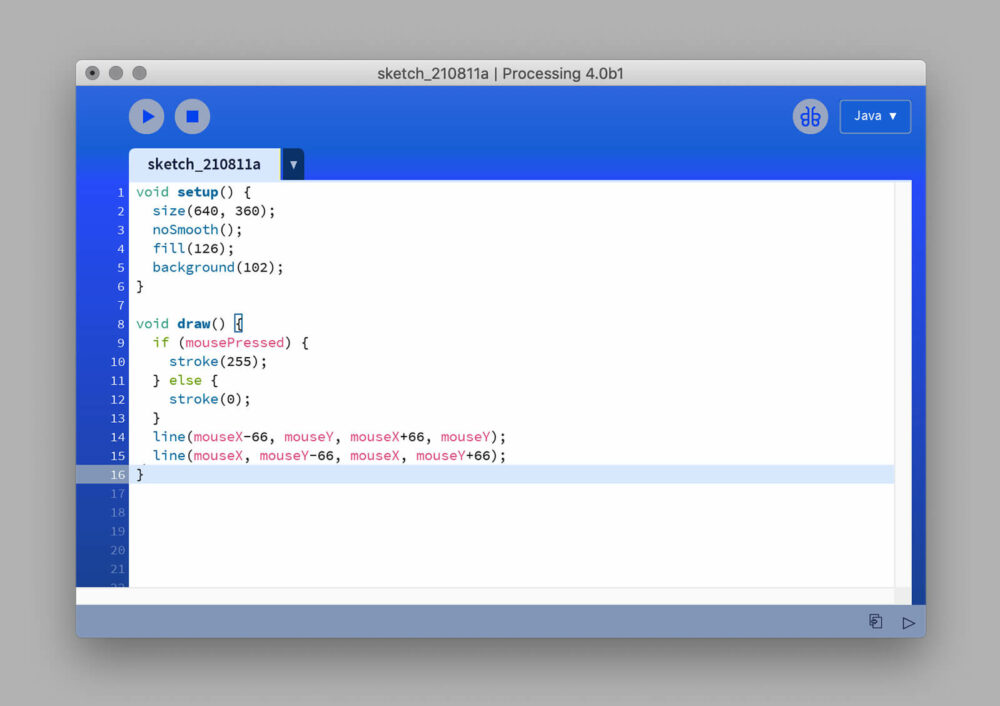

Dorothy R. Santos

Dorothy R. Santos

Dorothy R. Santos is the Executive Director of the Processing Foundation. Overseeing the foundation’s advocacy for software literacy in the visual arts, the San Francisco-based writer and curator has been integral in helping execute its mandate of increasing diversity in creative coding communities. In addition to her work for Processing, Santos is a co-founder of the REFRESH curatorial collective, which emerged in 2019 with a focus on inclusivity and promoting ”sustainable artistic and curatorial practices.”Keynote

Safa Ghnaim

Katja Melzer

Safa Ghnaim

Safa Ghnaim is a member of Tactical Tech, an international NGO that engages with citizens and civil-society organizations to explore and mitigate the impacts of technology on society. Lead of the Data Detox Kit and the forthcoming Digital Enquirer Kit project, before joining Tactical Tech Ghnaim developed partnerships and led workshops around the world.Pop-ups, prompts, notifications—smartphones are attention magnets that demand constant engagement and interaction. The business model of the internet is to capitalize on your attention. With some education and introspection we can regain some of our agency in this (over) stimulating media landscape.

We no longer have a clean division between online and offline anymore. The lack of a distinction brings complications with it—today we’re convening to consider that, as citizens and users, we need a digital detox.

Screen time is potentially nonstop and we have to reconcile that with the rhythm of the day, and our physiological need to rest and rejuvenate at night. You probably shouldn’t engage the internet the same way at 10pm as you do at 10am. Putting some thought into how and what you engage at night—setting limits—is an act of self care.

Ghnaim began by acknowledging that a “digital detox” is essentially impossible, since we increasingly rely on smartphones as a lifeline to connect us to essential services and to the social fabric of our communities near and far. We simply can’t just throw our phones into the ocean. Only folks in an enormous position of privilege can even entertain the notion, and, as Ghnaim pointed out—going cold-turkey isn’t sustainable, nor is it really the point. I couldn’t help but think of Jenny Odell’s book How To Do Nothing, which places digital detox culture in a historical lineage of absolutist refusal dating back to the Ancient Greek Epicurean garden school. The desire to drop out is all-too-common: Odell cites, too, the failed utopian communes of the ‘70s back-to-the-land movement and Silicon Valley’s current obsession with Seasteading. “Utopia,” of course, means “no-place,” and attempts to sidestep the world completely, however well-intentioned, lead to myopia, tyranny, and collapse. Instead of total renunciation, Odell argues instead for “refusal-in-place,” a way of “standing apart” from the world without running away from it. “To stand apart is to look at the world (now),” she writes, “from the point of view of the world as it could be (the future), with all the hope and sorrowful contemplation that entails.”

Roundtable

Celine Garcia, Nao Tokui, Noah Pred, Sarah Ciston

Nao Tokui

Nao Tokui is an artist, DJ, and researcher, and the founder of Qosmo, an AI creative studio based in Japan. While pursuing his Ph.D. at The University of Tokyo, he released his first album and other singles, including a 12-inch with Nujabes, the legendary Japanese hip-hop producer. Since then, he has been exploring the potential expansion of human creativity through AI.Part of artists’ responsibility is to misuse tools. Designers never anticipate what creatives will do with their inventions, and the tensions between designers and users pushes tools (and practices) forward. AI intervenes in this process, creating new opportunities for us to be surprised by art, and also necessitating new criteria for evaluating it.

Like the lawsuits over sampling that happened in the early 1990s, computer-assisted creativity will soon be the site of serious litigation. Many questions of copyright, influence, and derivative works will inevitably soon be in the spotlight, as we re-draw the boundaries between protecting intellectual property while making space for algorithmic (co-)creation.

Generative approaches to making art are liberatory. They free creators from centuries old rigid framings of where authorship begins and ends, while also creating some space between intent and execution—separating the artist’s ego from the work.

Celine Garcia

Celine Garcia is a manager and publisher who has produced numerous innovative musical projects. She is the project manager of French musician SKYGGE, who is at the vanguard of AI technologies and music creation. In 2017, she oversaw the publication of SKYGGE’s album, Hello World; shortly after, she joined together to found Puppet Master Label & Publishing in 2018.

Noah Pred

Noah Pred is a Canadian artist exploring generative audio-visual and multimedia installation work. A Juno-nominated producer, he has released on labels such as Cynosure, Highgrade, and Trapez LTD. Founder of the acclaimed Thoughtless imprint, Pred is an accomplished DJ who has toured worldwide. As a freelance sound designer, he has worked for Native Instruments and Ableton, among others.

Sarah Ciston

Sarah Ciston is a Mellon Fellow and PhD Candidate in Media Arts and Practice at the University of Southern California and a Virtual Fellow at the Humboldt Institute for Internet and Society in Berlin. Their research investigates how to bring intersectionality to artificial intelligence by employing queer, anti-racist, anti-ableist, and feminist theories, ethics, and tactics. They also lead Creative Code Collective—a student community for co-learning programming using approachable, interdisciplinary strategies.

Nao Taokui explains that the history of music technology is a history of misuse, misapplication, and misappropriation. The makers of the vinyl record had no way of anticipating turntablism, for example—that was an innovation brought by artists using records “wrong.” Another good example is the early history of the synthesizer and the drum machine, technologies initially created to replace live string sections and drummers for the purposes of creating inexpensive demo recordings. Many musicians at the time were seriously opposed to this. The British Musicians’ Union—bless their hearts—tried to ban synthesizers in the ‘80s. Ultimately, however, artists figured out how to use these tools “wrong,” pushing and bending them to create techno, hip-hop, New Wave, post-punk, house, and basically all the interesting music of the 20th century. This seems to happen again and again: technologies arrive that claim to simplify a process while implicitly displacing or automating creative workers, until creative workers stop that from happening by making the technology central to a new form of creative work that only they can do. It’s like defusing a bomb by turning it into an engine. Why should AI be any different?

The MUTEK Recorder

Claire L. Evans

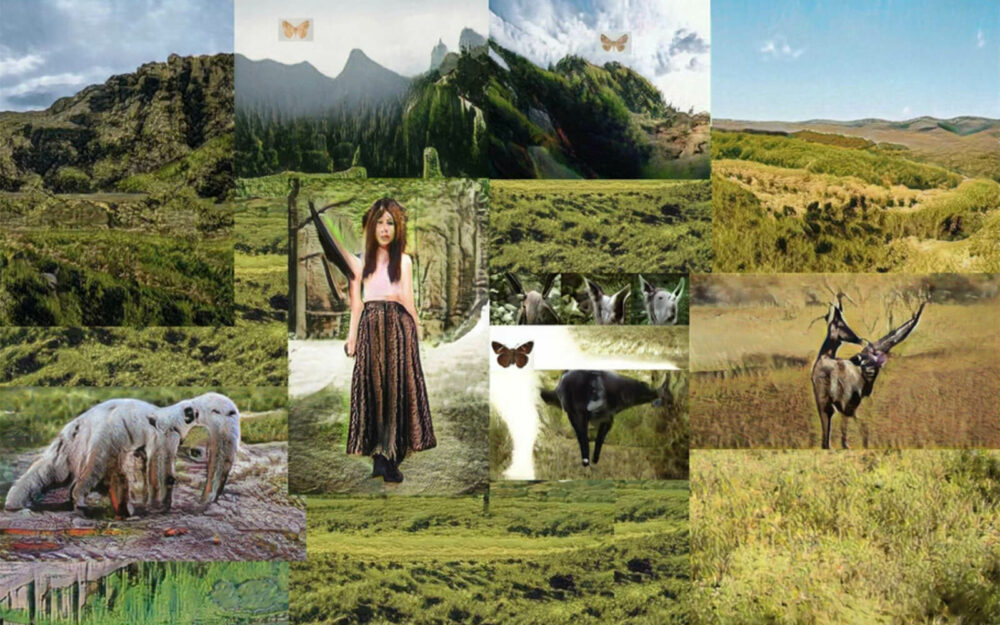

Xiaowei Wang

Xiaowei Wang

Writer and designer Xiaowei R. Wang is driven by beliefs in the “political power of being present, in dissolving the universal and categorical.” They are the Creative Director of Logic, and author of Blockchain Chicken Farm, a book that looks to rural China—not their homefront Silicon Valley—as a locus of tech-innovation. Wang’s recent artistic works include Future of Memory (2019-), an exploration of language and algorithmic censorship, and Shanzhai Secrets (2019), which explores consumption and copyright by way of Shenzhen.RED-BRAISED PIG TAILS

In large scale hog farming, stressed piglets bite each others tails off. Pig tails are a delicacy in the age of genetically modified, industrial hog farming where pig tails are being engineered out.

Ingredients:

1/2 inch stick of licorice, 1 tbsp of ginger, minced finely, 2 cloves of garlic, minced finely, 1/2 stick of Chinese cinnamon (cassia bark), 1 tbsp green Szechuan peppercorns, 3 star anise, 1 tbsp sugar, 1 bay leaf, 1 cup of soy sauce, oil, 1 pig tail, 2 eggs, cilantro, scallions

Preparation

- First, make eggs (for ludan, or soy eggs), boil eggs for 7 minutes and 30 seconds. Remove from heat and immediately put eggs in a cooling ice bath. Peel eggs, set aside.

- Fill a large wok with water and bring to a boil. Place the pig tail in boiling water and poach the pig tail for a minute. Remove the scum that floats at the top of the water. Remove pig tail and set aside.

- Dump the water out from the wok, making sure to dry the wok. In the dry wok, pour some oil. Put the pig tail into the wok, along with 1/2 a tbsp of sugar. Turn the heat to medium to carmelize the pig tail on both sides. Remove the pig tail once exterior has turned brown.

- In the wok, keep the oil at medium. Add in the minced garlic and ginger. Stir for a few minutes, until ginger and garlic become fragrant.

- Put the oil, ginger, and garlic into a clay pot. Add the pig tail, the two peeled eggs and the rest of the spices: cinnamon, licorice, Szechuan peppercorn, anise and bayleaf. Add the other 1/2 tbsp of sugar and soysauce. Put clay pot on stove and cover. For a soft boiled egg with jammy yolks, don’t put the soft boiled eggs into the pot—use the seasoning liquid as a cold bath and steep the eggs in the soy sauce mixture for up to 2 hours.

- Simmer at medium just until slightly bubbling, then turn heat to a low simmer for up to 2 hours. The longer you simmer for, the more flavorful the meat and eggs will become.

- Remove tail and eggs from heat, plate and garnish with scallions and cilantro.

Conversation

Ying Gao

Joanna Berzowska

Ying Gao

A Montréal-based fashion designer and professor at the Université of Quebec in Montréal, Ying Gao questions our assumptions about clothing by combining fashion design, product design, and media design. She explores the construction of the garment, taking her inspiration from the transformations of the social and urban environment. Her work has been featured globally, at venues including the Textile Museum of Canada, the San Francisco Museum of Craft and Design, and HeK Basel.For better or worse, fashion is is cyclical and animated by rhythms of obsolescence that drive consumption. What if fashion was a more sensitive register of what was happening in the world? We have haute couture, why not expand our conception of fashion to include clothes that are critical or speculative?

Like with art, fashion is about sparking the imagination of the viewer. Designers in interactive fashion and wearable technology are acutely aware of the centrality of representation. Unlike disposable ‘fast’ fashion, more conceptual designs wiill never be worn, so what or how they work (or how they were made) has to be communicated in other ways. To work in this field is as much about being a creative director or filmmaker as a designer of clothing.

Soft sculpture: Ying Gao’s shorthand for fashion-as-object, clothing that is ambiguous enough to escape being pigeonholed strictly as either ‘art’ or ‘design.’

Joanna Berzowska

Joanna Berzowska is the founder and research director of XS Labs, a design research studio focussing on innovation in the fields of electronic textiles and reactive garments. Her research involves the development of enabling methods, materials, and technologies—through soft electronic circuits and composite fibers—as well as exploring the expressive potential of soft reactive structures. Her work has been shown in the Cooper-Hewitt Design Museum in NYC, the V&A in London, the Millenium Museum in Beijing, and other venues.

Gao does not see herself as an ‘haute couture’ designer in the traditional sense, but her garments, like haute couture dresses, are not meant to be worn. Instead, they are “soft sculptures,” and when she considers the body, it’s the body standing outside, looking in. There is an element of post-human strangeness to Gao’s work, in this sense of fractured perspective between wearer and viewer, and because her garments have their own agency, are reactive, appear to breathe, as we breathe, continuously and unexpectedly. It’s beautiful but alienating, which is perhaps why Berzowska was so keen to pinpoint biological inspirations in Gao’s work, comparing her garments to octopi, the fractured perspective of houseflies, and even artificial organisms. Gao refused those interpretations, claiming to draw more inspiration from atmospheric phenomena like clouds, reflections, and mists. These, too, have a lifelike quality—biologically dead, but fluid, mutable, and volumetric. The biological and the chemical, the living and the dead, the metaphoric and the literal, the inevitable and the accidental—as much as Gao professed to compartmentalize, these are ambiguous dualities, especially when expressed through clothing. Perhaps because clothing is the permeable boundary between the body and the world, it can exist in a state of perpetual negotiation.

Panel

Damien Roach, Lindsay Howard, Matthew McQueen, Phillipe Aubin-Dionne, Shawn Reynaldo

Damien Roach

Damien Roach records under the alias patten, and works more broadly across design, installation, film, and live performance. His recent work includes shows at the ICA and Tate Modern in London, an AV tour with SHAPE Platform in 2019, and creative direction and design for Caribou’s Jiaolong label & Daphni project, and animation & artwork for Nathan Fake’s ‘Blizzards’ LP. He is also the force behind the 555-5555 web forum following his creative agency of the same name.

Lindsay Howard

Lindsay Howard is the Head of Community at Foundation. A distinguished curator and expert in contemporary art, Howard has spent the last decade organizing projects with the New Museum, Museum of the Moving Image, Kickstarter, Eyebeam Art and Technology Center, and Phillips Auction House. She has written and spoken extensively about digital art and new approaches to valuation, and serves on the board of Rhizome, an organization that champions born-digital art and culture.A common refrain amongst the musicians in this session was that in less than a year, everyone has had their understanding of what selling music is or could be turned upside-down. Albums now feel quaint, touring no longer needs to be a given. The direct connection between NFT creator and buyer eliminates layers of intermediaries (labels, publishers, festivals, venues) and forces a rethinking of what good or service musicians can make, and might want to make.

Stepping back from audience reach and sales numbers, the panelists engaged in a broader conversation about value. There was considerable excitement about moving beyond the thinking associated with fiat currencies as cryptocurrencies like Ethereum (or Tezos, Solana, etc.) can serve as more than just ‘another medium of exchange’—but also enact different ways of conducting business and mediating relationships.

she256

One of Lindsay Howard’s first Foundation projects was connecting with she256. Formed in 2018, the California-based organizations runs a steady stream of events—‘Crypto Taxes Tips & Tricks,’ ‘NFTs 101’—and a Discord to usher under-represented communities into crypto. The group’s goal: set an inclusive “culture and tone” while the blockchain space is still forming and ripe for influencing.

Matthew McQueen

Recording as Matthewdavid, Matthew McQueen is an experimental all-genre artist and musician from Los Angeles. He is the founder of Leaving Records, a label established in 2008 whose roster of artists includes Dntel, Laraaji, and Ras_G.

Philippe Aubin-Dionne

Jacques Greene is the artist name of Montréal-born and raised DJ and producer Philippe Aubin-Dionne. Between producing for artists like Katy B, Tinashe, and How To Dress Well, he has remixed acts including Radiohead, Flume, Rhye, and MorMor. Aubin-Dionne’s productions include the genre defining “Another Girl,” a revered and widely imitated house anthem with future R&B leanings.

I appreciate the candor with which the panelists discussed the pushback they received as a consequence of releasing NFT projects during the peak moment of NFT hype in February-March of this year. Matthewdavid talked about losing sleep; Jacques Green observed that musicians bore the brunt of social media’s fire and brimstone. My own band released a series of NFT stems in March 2020, and I can speak to how heated that moment was—I didn’t get much sleep either. In retrospect, it feels like a moment of collective hysteria, compounded by an extraordinary irony: the one thing that promised to rescue musicians from a year of extreme financial precarity was precisely the thing that most enraged and alienated a substantial portion of their fanbase. Thankfully the conversation has evolved, along with the technology. We now have secondary markets, social tokens for fan communities, and new forms of collective ownership and governance. As Foundation’s Lindsay Howard pointed out, artists have pushed the space forward by pushing buttons and inciting conversation. We must continue to do that—while also making sure that we do not reaffirm the existing hierarchies of the art world or bring the music industry’s more pernicious policies with us into the metaverse.

The MUTEK Recorder

Claire L. Evans

Jürg Lehni

Jürg Lehni

Making his mark on digital art over the last two decades, Jürg Lehni has mobilized Hektor, Rita, and Viktor, a series (2002-) of quirky drawing machines, as platforms for research on representation and histories of technology. Parallel to his robotic storytelling, the Zurich-based artist and designer has made open software for others, including the prescient Adobe Illustrator plug-in Scriptographer (2001-12) and, more recently, the browser-based “Swiss Army knife of vector graphics” Paper.js (2011-).Keynote

Michael Casey

Catalina Briceno

Michael Casey

Michael Casey is Chief Content Officer at CoinDesk, the leading media platform for the blockchain and digital asset community. He writes CoinDesk’s weekly Money Reimagined newsletter and co-hosts the podcast. Casey is also cofounder of Streambed Media, a blockchain-based digital rights management platform. Prior to joining CoinDesk, Casey was a senior lecturer at MIT Sloan School of Management and on-staff Senior Advisor at the MIT Media Lab’s Digital Currency Initiative, where he maintains a pro bono advisory role.We live in an age of abundance where (some) have access to resources, content, you name it. However, one resource that is not abundant is attention. We all have myriad actors competing for our attention—which makes it tremendously valuable.

An immediate benefit of the NFT economy is seeing marginalized creators flourish. A stodgy institution like Soethby’s is a gatekeeper, arbiter of taste, and caters towards a very particular (white) audience. Decentralized platforms make it easier for marginalized creators to bypass middlemen and all their historical baggage.

After the NFT collectible craze we may see massive disruption in fundraising. The smart contract terms that direct a portion of secondary sales to creators can easily be used to seamlessly fundraise for worthy causes—piggybacking philanthropy on top of this booming corner of the economy.

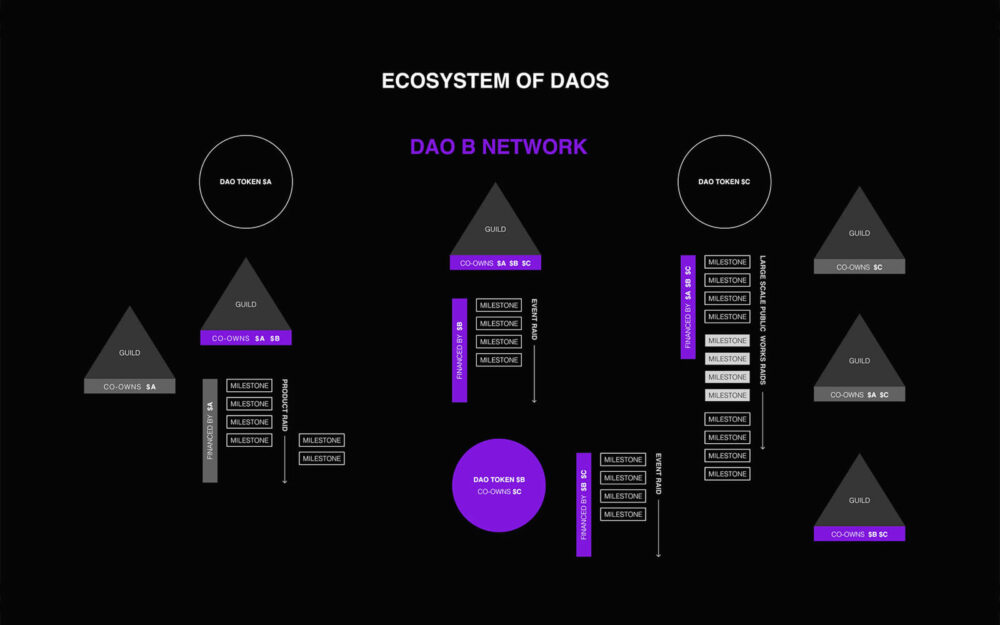

Decentralized Autonomous Organizations aren’t on the horizon—they’re already here. A tangible manifestation of crypto’s foundational decentralization, blockchain-powered governance is already being used in all kinds of communities. It’s early days (and a nascent toolkit) but we’re embarking on what will be an ambitious experiment in how organizations, fandoms, investor collectives, record labels, and you name it are co-managed by communities. Will this result in efficient synergy or more middling decision making? Time will tell.

Catalina Briceno

As a seasoned Executive and Scholar, Catalina Briceno addresses the digital transition of the media and cultural industries in her research work. Her expertise is based on 20 years’ hands-on experience as an executive producer, followed by decision-making positions within government-related organizations. She is currently a professor for the School of Media at UQÀM where she teaches Media Economy, Strategic watch and Foresight, as well as Information and Network architecture.

Michael Casey cited Silicon Valley’s current buzzword of choice: the “metaverse.” As a longtime reader of science fiction, I’m bemused by the universal adoption of this term to describe the virtual real estate of the coming crypto-era. As the writer Brian Merchant recently pointed out in a piece for VICE, the “metaverse” has always been a dystopian idea. The word comes from Neal Stephenson’s Snow Crash—in that novel, the metaverse is a successor to the internet, a massively multiplayer online game that entertains the desperate denizens of a world overrun by mercenaries and corporate overlords. While the metaverse serves as an escape from reality, it reaffirms its hierarchies and exclusions: the poor wear low-quality avatars and have limited access to the gated communities of the virtual world. This isn’t the first time that Silicon Valley has missed the point of its favorite science fiction novels—don’t get me started on cyberpunk—but I hope the leaders in this space take pains to ensure that the leap from IRL to the metaverse isn’t over another yawning digital divide.

The MUTEK Recorder

Claire L. Evans

Tim Maughan

Tim Maughan

Hailing from the UK and now based in Ottawa, Tim Maughan traces the contours of contemporary phenomena including logistics and complexity as a journalist and technology pundit, which informs his science fiction. His debut novel Infinite Detail (2019), which wryly imagined a post-internet future, was heralded as Sci-Fi book of the year by The Guardian. He has also written screenplays for the experimental short films Where the City Can’t See (2019) and In Robot Skies (2018), both directed by Liam Young.Keynote

Viktoria Modesta

David Hershkovits

Viktoria Modesta

Viktoria Modesta is a bionic pop artist and creative director. Brought up in London and now based in LA, Modesta is known for her multidisciplinary approach to future pop and performance art with a posthuman edge. Her work embodies sci-fi in real life bridging music, body art, sculptural tech-fashion, and an otherworldly narrative. Modesta changed the world’s perspective on post-disability when she performed as the Snow Queen during the Paralympics 2012, wearing a diamond-encrusted prosthetic.Viktoria Modesta is a self-described ‘bionic popstar’ and the fact that framing is so singular is compelling. In all her augmented fierencess, she commands a spot in the pantheon of what a popstar (or anti-popstar) might be alongside fellow trailblazers Arca or Sophie. While pop stars might not have quite the same wattage they used to, they might be getting more interesting. And a line of reasoning Modesta kept returning to that was tantalizing was the idea of ‘constructing’ a popstar or diva as making an avatar or worldbuilding.

As with feature films, pop stars are constructs that emerge from the collaboration of large multidisciplinary teams—but all too often erroneously attributed to a ‘lone auteur.’ Viktoria Modesta was refreshingly candid about how her ideas emerge from close collaboration with niche specialists spanning not just cinematography and production but wearable tech and software art.

Like many creators Viktoria Modesta used the Foundation platform to capitalize on her pop culture cache at the peak of the first wave of NFT mania. Distilling her “Prototype” video ‘spike dance’ sequence down to its most iconic moments—stripping away the song entirely—it serves a posthuman ballet of measured footsteps and scraping metal. Given the video‘s cultural impact, the short animation commanded an expectedly high fee of 30 ETH (worth $52,000 USD, at the time).

David Hershkovits

David Hershkovits is the founder of Paper magazine and currently hosts The Light Culture podcast where he interviews cultural disruptors of the past, present, and future. Steeped in the legacy of New York in the 80s, he focuses on the crossover of creative scenes and movements from the underground to pop. He has written for many publications and taught at University of New Orleans and in the School of Media Studies at CUNY, Queens College.

Modesta’s disability, the fact that she is missing a piece of her biological body, has given her a sense of the body as a mutable tool, which can be adapted, refined, and modified to suit different purposes. It’s also given her a sensitivity to the experiential aspects of identity—how it feels to be able to swap out parts of yourself. She brings this perspective to the formation of her digital identity, and seems energized by the idea of porting her work to the metaverse. Modesta indicated that the pandemic has served as a catalyst for people to take virtual identity seriously, largely because virtuality has become a more embodied experience—we’re living on our computers, she says, and suddenly realizing “wow, this is real life.” She hopes that people, contending with the limited mobility of their quarantine experiences, will start to think more deeply about what their body is, and how it interfaces with technology. Of course, people with disabilities have always been at the forefront of these questions, particularly when it comes to embodiment in virtual space. I think it’s instructive to look at the disability community in Second Life, which has been thinking through these issues for decades. A key reference for me is Our Digital Selves: My Avatar is Me, a documentary exploring the experiences of 13 people with disabilities in the virtual worlds of Second Life, High Fidelity, and Sansar, which was the product of a three-year research study on embodiment and placemaking in VR.

The MUTEK Recorder

Claire L. Evans

Benjamin Bratton

Benjamin Bratton

Benjamin Bratton is Professor of visual arts at UCSD in San Diego, and author of The Stack (2016) and The Revenge of the Real (2021), which, respectively, schematize systems of scale and governance after Big Tech, and consider what politics in a post-pandemic world could be. Bratton is also the Program Director for The Terraforming, an initiative at Moscow’s Strelka Institute that tasks design students with tackling the radical transformations required for Earth to remain a viable host for life.

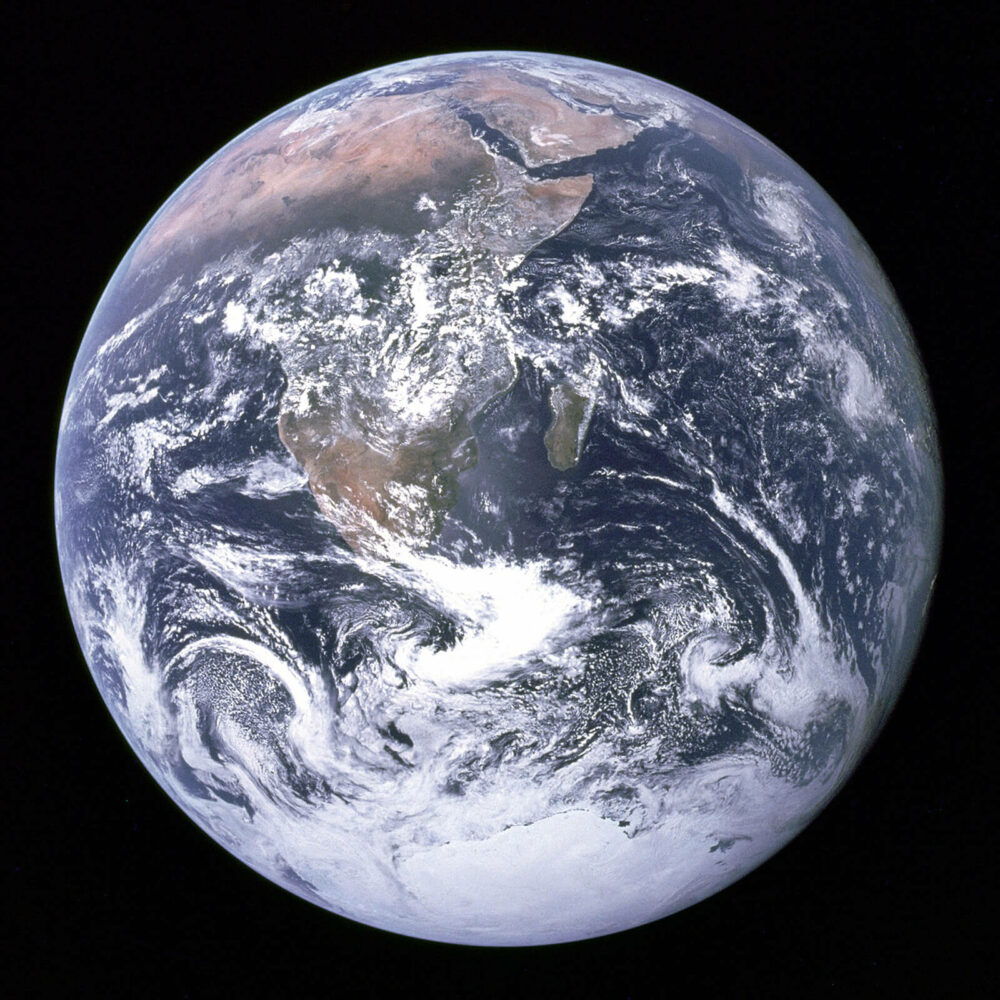

The Blue Marble

Taken on December 7, 1972, by Apollo 17 astronauts Harrison Schmitt and Ron Evans while en route to the Moon, The Blue Marble is one of the most circulated photographs in history. Benjamin Bratton notes “what Frank White called the Overview Effect—it preceded Yuri Gagarin, it preceded not only the Blue Marble but humans in space. It was conceived and announced in advance in the 1940s and ‘50s.” Even before we had the iconic image we had an idea about how it would stir our imagination about planetary unity.Claire L. Evans is a writer and musician based in Los Angeles. She is the singer and coauthor of the Grammy-nominated pop group YACHT, and the founding editor of Terraform, VICE‘s science-fiction vertical. She is also the former futures editor of Motherboard, and a contributor to VICE, Rhizome, The Guardian, and many other publications. Her 2018 book, Broad Band, tells the history of the female visionaries at the vanguard of technology and innovation.

For two weeks we lived the MUTEK Forum, documenting talks, roundtables, and workshops in real time. I’ll spare you our big takeaways from the Forum itself—the palpable excitement about decentralization, the collective desire to reframe artificial intelligence as tool and collaborator, or the eternal tension between the humanities and the sciences—as these are all contained in our sprawling dossier, in the form of soundbites and learnings. Instead I want to focus on the act of recording itself.

The MUTEK Recorder was a real-time publishing experiment. We worked under the watchful eye of the clock: up first thing in the morning and right into the thick of it, transcribing, translating, and free-associating live, synthesizing disparate conversations in time for an afternoon broadcast. There was no time to sit with our thoughts; we were forced to reflect as we went, in God mode, getting it all down for posterity. For something that required total presence, it was oddly dissociative. We were in the moment, at a distance. Jokingly, I called our syndrome documentia.

In his opening keynote, Benjamin Bratton cited Derrida: “the archive is a promise to the future that the present time will make itself accountable,” he said. “It can also be a technology to ensure that the future is even possible in the first place.” I wonder if our work recording MUTEK is quite the same as an archive. By virtue of how quickly we worked, we could never claim to have produced something so complete. And our small group, each of us guided by of our own interests, interpreted the Forum’s conversations subjectively.

I couldn’t help but spin up anecdotes from my own research, for example, or pull references from my library shelves. The practice of recording in this way became self-reflexive. A panel about sound intensity in electronic music awoke my tinnitus, reminding me of the obliterating drone of a NASCAR race; a conversation about procedural game maps conjured the time, years ago, that a friend and I tried to swim across the ocean in Grand Theft Auto V.

Maybe what we produced was not an archive at all, but a memory palace. The Romans called it the “method of loci,” of places: to remember things, imagine them in the rooms of a house you know well, then wander its halls, recalling. Roman orators would prepare long speeches in the rooms of imagined houses; each orator had their own memory palace, an empty architecture that could be filled and filled again with new ideas. In the modern world, we have little need for such techniques, which emerged before writing. But the mechanism retains its archaic power.

The Romans enlisted their greatest technology, architecture, in the service of memory; perhaps our virtual architecture—a dossier, embedded on the World Wide Web—could do the same. I might wander these rooms in a year and remember the conversations that echoed within, which in turn may invite their own memories, their own interpretations. I might also find new tenants in their place: the foundations of the Web are never solid.

Of course, there are other, fine approaches. Our guests were generous enough to share a few: Mindy Seu builds archives, Xiaowei Wang uses recipes to record in the field, and Tim Maughan captures the present in science fiction stories. We all have our tools for thinking, each with their own shape. Perhaps by including all of these approaches, our Recorder was something more like a toolbox—a collection of strategies, suited to different applications, stress-tested and ready to work. Perhaps the mark of a successful project is how well it resists being defined by such neat metaphors.