HOLO 3: Myths of Prediction

Prompt 2: On Myths of Prediction Over Time

“Prediction has always been part of our cultural heritage, and societies find scientific ways to sort and distribute resources based on biased predictive thought.”

“Prediction has always been part of our cultural heritage, and societies find scientific ways to sort and distribute resources based on biased predictive thought.”

“As we struggle to disentangle ourselves from predictive regimes and algorithmic nudging, we need to tackle what prediction means, and has meant, for control and computation.”

Nora N. Khan is a New York-based writer and critic with bylines in Artforum, Flash Art, and Mousse. She steers the 2021 HOLO Annual as Editorial Lead

The first wave of HOLO contributors—Nicholas Whittaker, Thomas Brett, Elvia Wilk, and Huw Lemmey—swiftly gathered around the “ways of partial knowing.” As these pieces started to roll in, Peli Grietzer and I needed to light a new fire in another clime for more contributors to gather around. Maybe it is endemic to technological debates that we are drawn into intense binaristic divides. But I started to look across to the other side of the art-technological range, across from the ‘ways of partial knowing’ that seem to offer looseness, a space to breathe. Claims to full knowing, full ownership, or full seeing seem, rightly, harder to sustain these days. I’d written the partial knowing prompt in response to the suffocating grip of algorithmic prediction that I spend my days tracking and analyzing, to see how others articulate senses of the impossibility of perfect prediction, of human activity or thought.

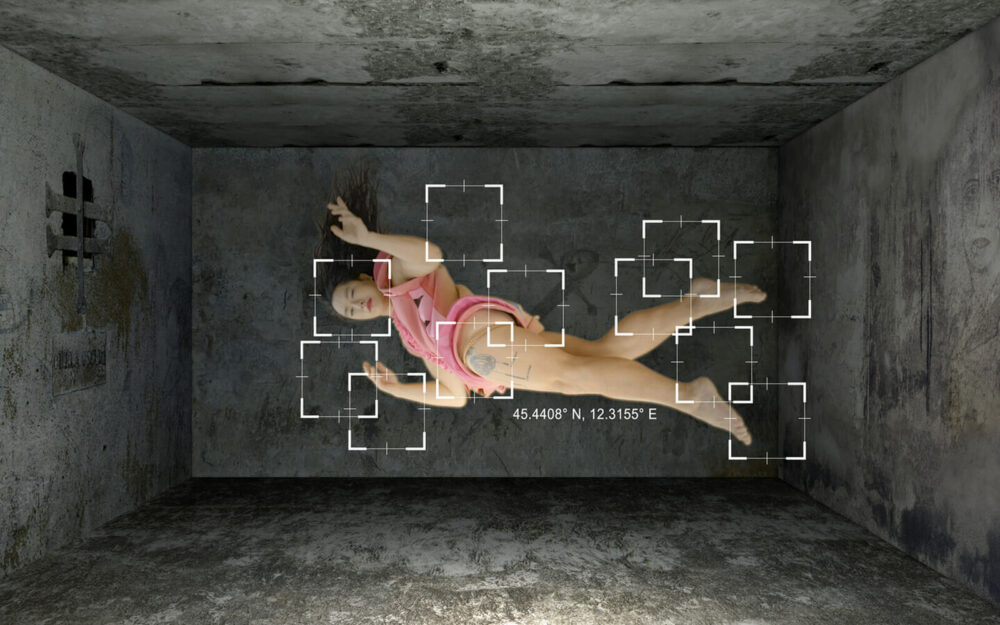

But of course, there are many ways that prediction has always been part of our cultural heritage, and societies find scientific ways to sort, predict, and distribute resources based on biased predictive thought. I’ve a soft spot for critical discussion of predictive systems of control and the artists and theorists who analyze them. I’ve looked to thinkers like Simone Browne and Cathy O’Neill and Safiya Noble and artists like Zach Blas and American Artist, most frequently, for their insights on histories of predictive policing, predictive capture, and the deployment of surveillance in service of capture. I was particularly taken by 3x3x6, the Taiwan Pavilion at the 2019 Venice Biennale, created by Shu Lea Cheang, director, media and net art pioneer, and theorist Paul Preciado. (Francesco Tenaglia’s precise interview with both artists in Mousse is a must-read).

In the space, the Palazzo delle Prigioni, the two investigated the history of the building as a prison, and the exceptional prisoners whose racial or sexual or gender nonconformity led to incarceration: Foucault, the Marquis de Sade, Giaconomo Casanova, and a host of trans and queer thinkers throughout history. The work looks at historical regimes and political definitions of sexual and racial conformity, and the methods of tracking and delineating correct and moral bodies over time: the ways myths of prediction have unfolded in different ways throughout history.

I used these photos and this interview as inspiration this last pandemic year, which I largely spent struggling to complete an essay on internalizing the logic of capture for an issue of Women & Performance: a journal of feminist theory (with an incredible list of contributions). In their introduction, Marisa Williamson and Kim Bobier, guest-editors, outline the theme Race, Vision, and Surveillance: “As Simone Browne has observed, performances of racializing surveillance ‘reify boundaries, borders, and bodies along racial lines.’ Taking cues from thinkers such as Browne and Donna Haraway, this special issue draws on feminist understandings of sight as a partial, situated, and embodied type of sense-making laden with ableist assumptions to explore how racial politics have structured practices of oversight. How have technologies of race and vision worked together to monitor modes of being-in-the-world? In what ways have bodies performed for and against such governance?”

“Our ways of understanding others are speculative and blurry—how is this blur coded and embedded, and what prediction methods that aim to clarify the blur are possible?”

“Four powerhouse thinkers were asked to think about the rise in magical thinking around prediction and the capacity of predictive systems to become more ruthless.”

The gathering of feminist investigations drew on surveillance studies and critical race theory to theorize responses to the violence of racializing surveillance. Between the theorists in this issue and the impact of 3x3x6, it seemed to me that surveillance-prediction regimes of the present moment must be understood as a repetition of every regime that has come before.

In a way, it turned out that the prompts of ‘partial knowing’ and ‘myths of prediction’ are more linked than opposed: Our ways of understanding others are already quite speculative and blurry; how is this blur coded and embedded, and what prediction methods that aim to clarify the blur, or make the blur more precise, are possible?

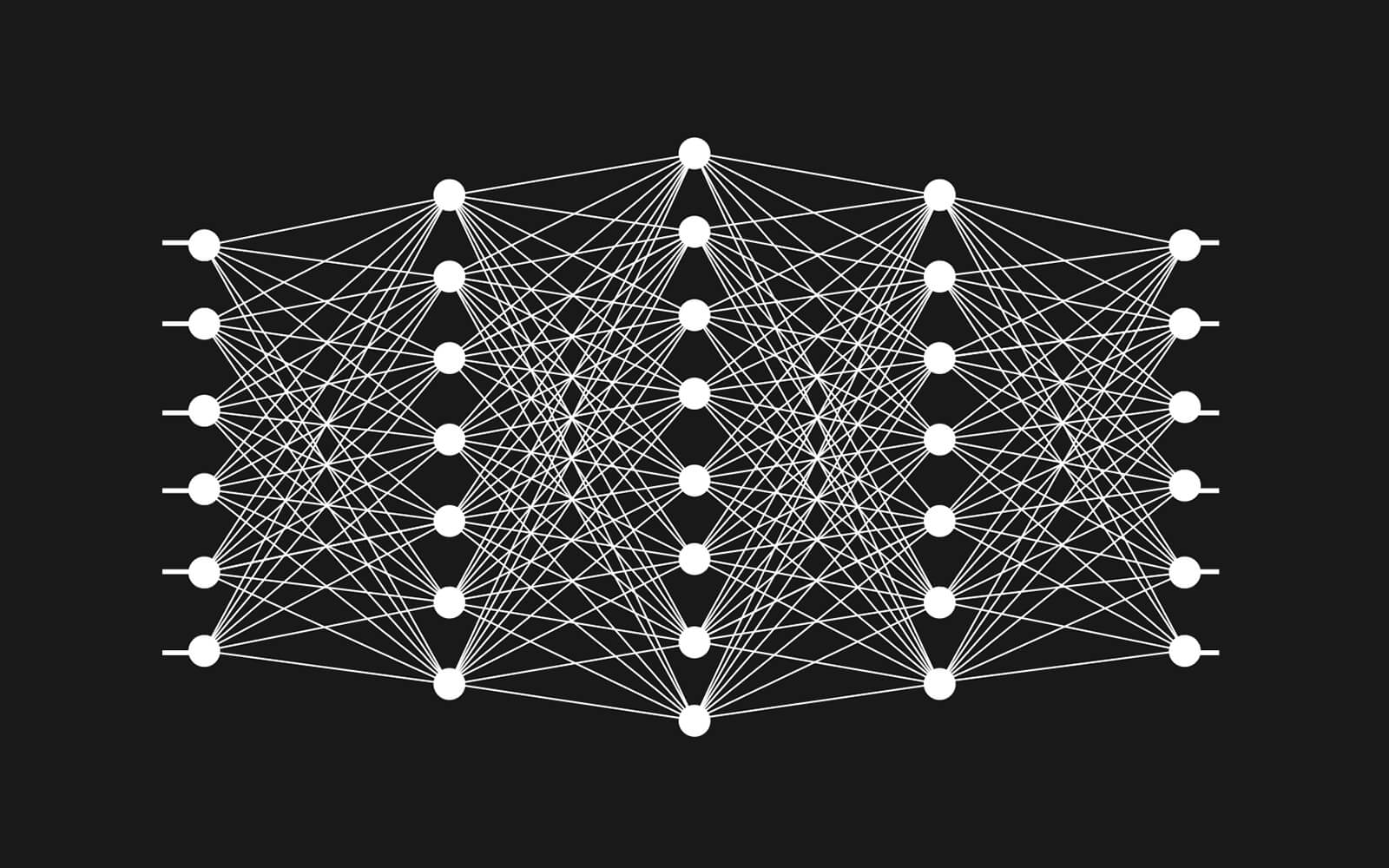

Even as we struggle to find ways to disentangle ourselves from predictive regimes and algorithmic nudging, we also need to tackle what prediction means, and has meant, for control, for statistics, for computation. This second prompt includes hazy, fuzzy, and over-determinant methods of prediction and discernment. The future, here, is one entirely shaped by algorithmic notions of how we’ll act, move, and react, based on what we do, say, and choose, now—a mediation of the future based on consumption, feeling, that is subject to change, that is passing.

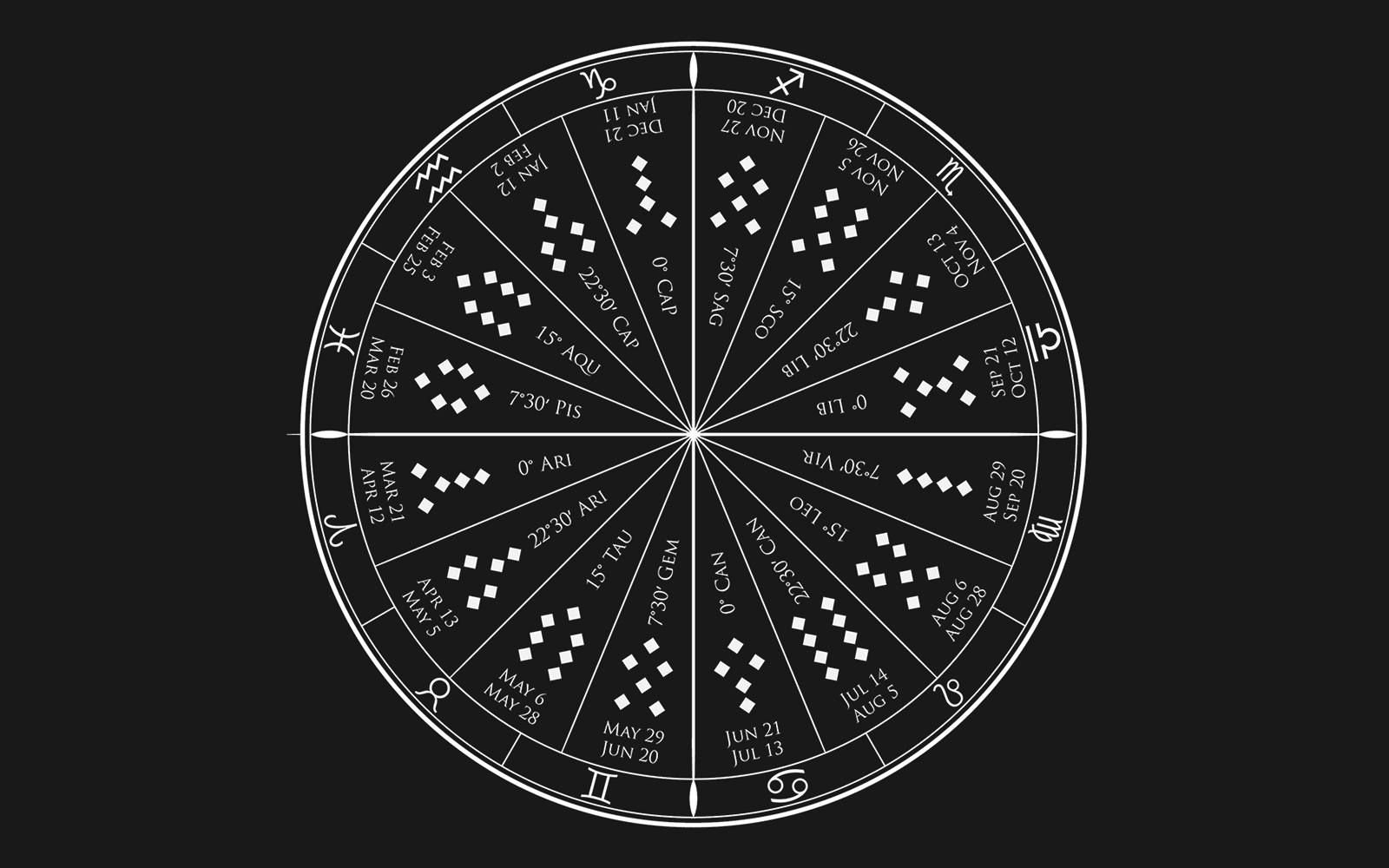

Four powerhouse thinkers—Leigh Alexander, Mimi Ọnụọha, Suzanne Treister, and Jackie Wang—join the Annual to respond to this prompt, Myths of Prediction Over Time. They were asked to think about the rise in magical thinking around prediction and the capacity of predictive technologies to become more intense as technological systems of prediction become more ruthless, stupid, flattening, and their logic, quite known. They look at the history of predictive ‘technologies’ (scrying and tarot and future-casting) as magic, as enchantment, as mystic logic, as it shapes the narratives we have around computational prediction in the present moment.

Together, they are invited to consider the algorithmic sorting of peoples based on deep historical and social bias; at surveillance and capture of fugitive communities; at prediction of a person’s capacity based on limited and contextless data as an ever political undertaking, or at prediction as they interpret it. They might reflect on the various methods for typing personalities, discerning character, and the creation of systems of control based on these partial predictions. They are further invited to look both at predictive systems embedded in justice systems, or in pseudoscientific tests like Myers-Briggs, for example, embedded in corporate personality tests.

Wang, Ọnụọha, Alexander, and Treister are particularly equipped to think on these systems, having consistently established entire spaces of speculation through their arguments.

Jackie Wang wrote the seminal book Carceral Capitalism (2018), a searing book on the racial, economic, political, legal, and technological dimensions of the U.S. carceral state. A chapter titled “This is a Story about Nerds and Cops” is widely circulated and found on syllabi. I met Jackie in 2013 as we were both living in Boston, where she was completing her dissertation at Harvard. She gave a reading in a black leather jacket at EMW Bookstore, a hub for Asian American and diasporic poets, writers, activists. I’ve followed her writing and thinking closely since. Wang is a beloved scholar, abolitionist, poet, multimedia artist, and Assistant Professor of American Studies and Ethnicity at the University of Southern California. In addition to her scholarship, her creative work includes the poetry collection The Sunflower Cast a Spell to Save Us from the Void (2021) and the forthcoming experimental essay collection Alien Daughters Walk Into the Sun.

Mimi Ọnụọha and I met at Eyebeam as research residents in 2016, and our desks were close to one another. One thing I learned about Mimi is that she is phenomenally busy and in high demand. She is an artist, an engineer, a scholar, and a professor. She created the concept and phrase “algorithmic violence.” At the time she was developing research around power dynamics within archives (you should look up her extended artwork, The Library of Missing Datasets, examining power mediated through what is left out of government or state archives).

Ọnụọha, who lives and works in Brooklyn, is a Nigerian-American artist creating work about a world made to fit the form of data. By foregrounding absence and removal, her multimedia practice uses print, code, installation and video to make sense of the power dynamics that result in disenfranchised communities’ different relationships to systems that are digital, cultural, historical, and ecological. Her recent work includes In Absentia, a series of prints that borrow language from research that black sociologist W.E.B. Du Bois conducted in the nineteenth century to address the difficulties he faced and the pitfalls he fell into, and A People’s Guide To AI, a comprehensive beginner’s guide to understanding AI and other data-driven systems, co-created with Diana Nucera.

If you’ve had any contact with videogames or the games industry in the last 15 years, Leigh Alexander needs no introduction. You’ve either played her work or read her stories or watched her Lo-Fi Let’s Plays on YouTube or read her withering and incisive criticism in one of many marquee venues. She is well-known as a speaker, as a writer and narrative designer focused on storytelling systems, digital society, and the future. Along with other women writing critically about games, including Jenn Frank and Lana Polansky, I’ve been reading and influenced by her fiction and criticism since 2008.

Alexander won the 2019 award for Best Writing in a Video Game from the esteemed Writers Guild of Great Britain for Reigns: Her Majesty, and her speculative fiction has been published in Slate and The Verge. Her work often draws her ten years as a journalist and critic on games and virtual worlds, and she frequently speaks on narrative design, procedural storytelling, online culture and arts in technology. She is currently designing games about relationships and working as a narrative design consultant for development teams.

Suzanne Treister, our final contributor to this chapter, has been a pioneer in the field of new media since the late 1980s, and works simultaneously across video, the internet, interactive technologies, photography, drawing and watercolour. In 1988 she was making work about video games, in 1992 virtual reality, in 1993 imaginary software and in 1995 she made her first web project and invented a time travelling avatar, Rosalind Brodsky, the subject of an interactive CD-ROM. Often spanning several years, her projects comprise fantastic reinterpretations of given taxonomies and histories, engaging with eccentric narratives and unconventional bodies of research. Recent projects include The Escapist Black Hole Spacetime, Technoshamanic Systems, and Kabbalistic Futurism.

Treister’s work has been included in the 7th Athens Biennale, 16th Istanbul Biennial, 9th Liverpool Biennial, 10th Shanghai Biennale, 8th Montréal Biennale and 13th Biennale of Sydney. Recent solo and group exhibitions have taken place at Schirn Kunsthalle, Frankfurt, Moderna Museet, Stockholm, Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin, Centre Pompidou, Paris, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, and the Institute of Contemporary Art, London, among others. Her 2019 multi-part Serpentine Gallery Digital Commission comprised an artist’s book and an AR work. She is the recipient of the 2018 Collide International Award, organised by CERN, Geneva, in collaboration with FACT UK. Treister lives and works in London and the French Pyrenees.

Stay tuned for more notes on the next two Annual prompts—on mapping outside language, and explainability—and the brilliant contributors on board. Also take note of the first in a series of research transcripts featuring conversation excerpts with our research partner Peli Grietzer about incoming drafts, the frame overall, and, well, all those atlases of AI.