AI Anarchies: Wildflowers and Broken Machines

Morning Provocation

Wildflowers and Broken Machines: A Tech Check for Feminist Philosophies and Politics

Speakers:

Sarah Sharma, Jac sm Kee, Maya Indira Ganesh, Nora N. Khan

Profile:

Sarah Sharma

Sarah Sharma is Associate Professor of Media Theory at and incoming director of the ICCIT at the University of Toronto. Her research focuses on the relationship between technology, time and labour with a focus on gender, race, and class issues. She is the author of In the Meantime: Temporality and Cultural Politics (2014) and co-editor of Re-Understanding Media: Feminist Extensions of Marshall McLuhan (2022).

Soundbite:

“I stand up here with a contradictory relationship I have with being somebody who thinks of themselves as a techno-feminist theorist who is very incapable technologically. But also, that makes me able to do weird things with technology, as you’ll see—I’m more interested in things like light bulbs than AI. That’s the spirit with which I come to this.”

Sarah Sharma, positioning her scepticism (and fascination) with technology

Takeaway:

Researchers can’t put their heads in the sand and pretend bad or influential actors in their field don’t exist. Sharma refers to spending time reading the “blogs of incels, tech bros, and masculinist and problematic media theory” as part of her work. By reading sources like these or alt-right voices, she is able to understand the rhetoric and ideology at play. Know thy enemy.

Takeaway:

Activists and critical researchers working against the interests of tech monoliths like Google or Meta should not assume those companies (and the entrepreneurs helming them) do not have a guiding ideology around what media shapes the social realm. To think or hope “there is no intelligible media theory” in the design or policy decisions made in Silicon Valley “might be a feminist misstep,” warns Sharma.

Soundbite:

“One of the things we were asked to think about as a prompt, is the kinds of terms and concepts we’ve inherited within techno-feminism. And I think this is super interesting, because techno-feminism only operates with an inherted technology world. And with an inherited intellectual canon of media theory. So there’s a lot we’ve inherited, and how do we work within this inheritance?”

Sarah Sharma, positioning her scepticism (and fascination) with technology

Precedent:

Going after an always-on corporatized personal virtual assistant might seem like low hanging fruit for a media theorist but Sharma’s reading goes beyond the usual commentary on Alexa’s (seeming) female gender. Sharma is interested in “how Alexa itself reorchestrates the labour of others” and that network of relations that connects a desire for detergent with an Amazon driver setting in motion from a fufillment centre. Amazon’s device “expands the world of social reproduction and consumption,” says Sharma.

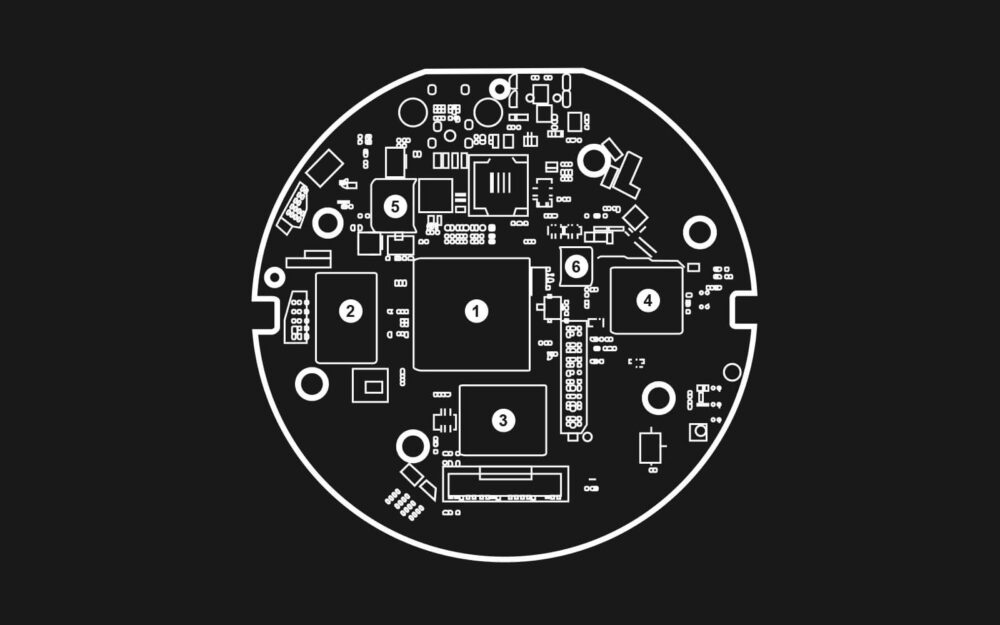

Image: Kate Crawford & Vladan Joler, Anatomy of an AI System (2018)

Image: Kate Crawford & Vladan Joler, Anatomy of an AI System (2018)

Soundbite:

“When Elon Musk launched his Tesla Roadster into space, he tweeted out a photo of Marshall McLuhan with no accompanying words. I found it a little ominous and creepy.”

Sarah Sharma, starting her discussion with the biggest tech bro of all

Soundbite:

“In McLuhan’s key text Understanding Media, there is a phrase that is often passed over. Quote: ‘Man becomes, as it were, the sex organs of the machine world. As the bee of the plant world, enabling it to fecundate and evolve ever new forms. The machine world reciprocates Man’s love expediting his wishes and desires, namely in providing him one wealth.’ And that is to me, one of the creepiest lines of what is going on, when I see Elon Musk tweeting that photo of McLuhan.”

Sarah Sharma, lining up Musk’s actions with McLuhan’s words

Precedent:

As a scholar based in Toronto, part of Sharma’s taking media theory’s patriarchal legacy to task involves engaging the late media theorist Marshall McLuhan. A pop-culture sensation in the 1960s and ’70s, his most well known work is Understanding Media (1964), which makes a broad case for how new mass media (television, film, radio) were engaging human senses differently than print culture; and also that new media retrieves old cultural forms. Of particular relevance to Sharma’s talk is McLuhan’s reading of the light bulb, which she uses to demonstrate the limitations of his analysis. Sharma brought her aspirations for a more inclusive media theory to the University of Toronto McLuhan Centre named after the scholar, serving as its director from 2017-22.

Soundbite:

“McLuhan never got the full message of the light bulb. The techno-feminist reading of the light bulb would have us focus on something else—not just day and night or a shifting definition of day—the lightbulb, for example, shifted the gendered labour of the day and ushered in a new politics of night. Replete with new subaltern politics, transgressive politics, and even different modes of policing become possible.”

Sarah Sharma, picking up and extending McLuhan’s reading of the light bulb

Soundbite:

“Latent and blatant within these conceptions of media that dominate our culture, one of the other connections I’ve been making is that these tech elites operate with a conception of technology that also explains how they think of social difference. There are also clues in the designs of the products they make.”

Sarah Sharma, on trying to reverse engineer masculinist and tech bro philosophy through studying their talk and actions

Soundbite:

“There’s an overriding misogynistic formulation of women as technological tools. And feminists, and all the other non-abiding—it’s not just about women, it’s about the non-confirming and non-abiding—as broken tools. In other words, feminists are the abberations of otherwise well-working tools.”

Sarah Sharma, distilling misogynistic overtones emanating from the alt-right (and fairly recent media theory)

Soundbite:

“I find it really interesting that Big Tech is invested in design, in media theorizing, and machine logics. But their feminism campaigns are turned away from technology and only focus on the workplace—and ameliorating any difficulties.”

Sarah Sharma, on where Big Tech does and doesn’t engage gender

Profile:

Jac sm Kee

Jac sm Kee is a feminist activist working at the intersection of internet technologies, social justice and collective power. Kee’s activism includes sexuality and gender justice, feminist movement building in the digital age, internet governance, open culture, and epistemic justice. A co-founder of the Take Back the Tech! collaborative campaign on ending online gender-based violence, Kee also stewarded the development of Feminist Principles of the Internet.

Soundbite:

“A big part of my practice is to make technology intelligible to feminism. And to make feminism intelligible to technology.”

Jac sm Kee, sharing her job description

Soundbite:

“For the last ten years, I’ve been really lucky to work with some of the most inspiring feminists, thinking about and pushing and engaging with technology in the larger world, or what we call the majority world—what used to be known as the Global South. Activists in Brazil, Mexico, Keyna, Indonesia, Bosnia, and India.”

Jac sm Kee, speaking to her collaborative (and global) practice

Takeaway:

Activists don’t always need to be organizing around a specific cause or goal. One of Kee’s responses to the drastic change of pace (slowness) of the pandemic was to try to get many of her favourite feminists and artists together without a goal in mind—to brainstorm. “It’s about really creating an extended process of imagining together,” she says of the loose collectives she participated in that led to several design projects and initiatives.

Takeaway:

Idealism comes much easier when you’re young and bright-eyed. Kee shares how when she was a “baby feminist” the outlook on the inevitability of social justice was much rosier. Mid-career activists can and should make time for self-care and reflection to reevaluate assumptions—and also to rekindle the optimism that motivated them in the first place.

Soundbite:

“Initially it was very challenging. It’s so hard for activists to come together with no objective, without a purpose of change. But the purpose was for us to be in community with each other and inquire; and to inquire in the spirit of play. And we let go of the objective—of the capitalist logic of productivity and production.”

Jac sm Kee, talking about creating structures for play

Precedent:

A project by the Coding Rights and Design Justice Network that Kee helped shape is the Oracle for Transfeminist Technologies, a part-Tarot, part-feminist, and part-tech futures card game for brainstorming more inclusive futures. Card groups within the deck include values (intersectionality, interoperability) that can be combined with situations (rethink and reclaim pornography, grant unrestricted access to information), and objects (plant, mirror) to generate new technological and cultural configurations.

Soundbite:

“Now there are like three, maybe five companies shaping all of the tech infrastructure. Is it even possible to be online without Amazon, for example? It can feel extremely overwhelming.”

Jac sm Kee, contextualizing why it’s important to make space for cultivating feminist tech-imaginairies not oriented around monoculture

Precedent:

Many of the roots of Kee’s talk can be found in her 2021 DING essay “Tending to wildness: field notes on movement infrastructure,” in which the activist outlines where her thinking about platforms and social media started—and how the challenges of the pandemic changed it. “The seemingly desolate space of crisis can be a generous site for deep shifts and unruly imaginings of how things can be,” she writes, summarizing how the shortcomings of Zoom regime served as a way to rethink both her methods and priorities.

Soundbite:

“The famous Indonesian poet Wiji Thukul wrote about how to fight against a big autocratic state. If that autocratic state is a big wall, the way to defeat it is to create cracks in the wall by becoming persistent wallflowers—that will just live because they have to—and I imagine us becoming this cluster of wallflowers.”

Jac sm Kee, closing her talk with a poetic metaphor