Weaving Variations

Augmenting Molnar’s first U.S. solo exhibition, Zsofi Valyi-Nagy parses the legacy of the nonagenarian generative art pioneer.

Vera Molnar “Variations”

Apr 2–Aug 27, 2022

The Beall Center

for Art + Technology

Irvine, California (US)

© 2022 HOLO

Zsofi Valyi-Nagy is a PhD candidate in art history at the University of Chicago, where she is writing her dissertation on Vera Molnar and the intersection between abstract art and early computer graphics in Cold War Europe. She is currently based in Berlin as a DAAD fellow at the Media Archaeological Fundus/Signallabor at Humboldt University, and is also a predoctoral fellow at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. Her texts have appeared in Art Journal and Right Click Save; Zsofi is also a practicing artist.

“My work is like a textile,” Vera Molnar has told me, many times, over coffee, first in her home/studio in the fourteenth arrondissement of Paris, then in her sun-filled room at the nearby EHPAD, or retirement home, where she has lived since the summer of 2020. Molnar loves her coffee, and she squeals with delight whenever I show up at her door holding a thermos or two little paper cups. Like a textile—at least that’s how I can best translate the Hungarian word szövet that she uses, since we always speak in our shared mother tongue. At first I didn’t understand what she meant. But then she used her finger to trace a sinusoidal wave through the air, up and down along an imaginary x-axis. She was miming the weft, the thread that disappears behind the warp and then reappears again. Disappears, then reappears. Molnar doesn’t weave with thread—she makes paintings, drawings, and collages—but her metaphor perfectly captures the way ideas have moved, and continue to move, throughout her lifelong art practice.

Whether it’s the form of the concentric square or the continuous line, or the theme of the progression from order to disorder, Molnar is constantly revisiting her old ideas, creating unrealized works from her notebooks or reopening projects she hasn’t looked at in years. For her, nothing is ever really finished. There is always potential to come back, to see something from a new perspective. At ninety-eight, she is still bursting with new ideas, though her visual language is remarkably consistent, always remaining in the realm of geometry. For Molnar, it seems the square, the line, and the circle never go out of style. They are timeless.

This recursivity of Molnar’s work is one of its most compelling aspects, but it is also one of the most difficult to address in the traditional form of the art historical monograph. As I write my PhD dissertation on Molnar, parsing through the interviews, archival materials, and documentation of artworks I have gathered over the last five years, I become increasingly aware of the limiting structure of the monograph’s chronological structure and distinct chapters. How can I capture a nonlinear practice through such a linear form? I’m still figuring that out, but in the meantime, this is why I am particularly excited to lead this HOLO dossier. The way the dossier format weaves a narrative that unfolds over time, and that allows for nonlinear navigation across media, feels particularly amenable to Molnar’s work, and how I have been thinking about it.

And what better time to do this than on the occasion of Molnar’s first solo exhibition in the United States? “Variations,” curated by David Familian, is an important show not only because it is a first, or because it brings the remarkable Spalter Digital Art collection to a wider audience. “Variations” matters because the Beall does what very few institutions have had the space or the care to do: focus on Molnar’s works on paper, and show important series in their entirety. While most exhibitions will show one of her plotter drawings in isolation, framed and finished off with a date and signature (often alongside the work of other—mainly men—’Algorists’), at the Beall we can see the whole series together. We are invited to compare different steps in Molnar’s process, and to imagine what algorithms lie behind her pictures.

Over the next few months, we will take slow, virtual walks through this exhibition, pausing on specific artworks to look closely at them. I’ll be musing about Molnar’s processes behind the works, drawing on her writing as well our many conversations. Since my specific interest lies in the intersection of early computer graphics technology and abstract art, I will also be profiling specific computer hardware and programs that Molnar used in the 1970s and 1980s to create her work. Drawing on methods from media archaeology, I will also discuss how ‘reenacting’ her processes through creative coding can lend itself to art history as well as to contemporary media art practices and pedagogy. By sharing a combination of archival photos and anecdotes, vintage computing nerdery, and experimental writing, I hope to also weave something like a textile—and I invite you to explore its many threads with me.

Located in the Claire Trevor School of the Arts at UC Irvine in California, the Beall Center for Art + Technology was founded in 2000 in honour of Don and Joan Beall. Drawing on the arts and engineering interests of its namesake donors, it has served as an important North American hub for artist-led critical interrogation of emerging technologies through exhibitions, artist talks, and residencies. Over the last decade the Beall has featured artists including R. Luke DuBois, lauren woods, Christa Sommerer and Laurent Mignonneau, Zimoun, Golan Levin, and Nam June Paik.

The Vera Molnár exhibition was made possible with generous support from the Anne and Michael Spalter Digital Art Collection; the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts; the Beall Family Foundation; and Etant donnés Contemporary Art, a program of Villa Albertine and FACE Foundation, in partnership with the French Embassy in the United States, with support from the French Ministry of Culture, Institut Français, Ford Foundation, Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, CHANEL, and ADAGP.

“Though she used only traditional artists’ tools before working with an electronic computer in 1968, Vera remembers inventing systematic methods for making art from an early age.”

Vera grew up drawing and painting, so it was no surprise she would end up applying to art school. Here she is at age 17, on vacation in Mátrafüred, Hungary, about 85 kilometers northwest of her hometown Budapest. The photo is black-and-white, but Vera reminds me that her silver hair was once red—her signature color. Here, it’s pulled back in milkmaid braids. She wears a shirtdress covered in thick pinstripes that meet at 90-degree angles on the collar, framing her face in a pattern of concentric squares—her signature motif. Her style remains remarkably consistent to this day—at 98, Vera still dresses like the art she makes.

Teenage Vera flashes a proud smile as she looks up from the sketchpad in her lap. Though she used only traditional artists’ tools—colored pencils, paintbrushes, pastels—before working with an electronic computer in 1968, Vera remembers inventing systematic methods for making art from an early age. Vacationing with her parents in Balatonvilágos at the house they named Veronika after their beloved only child, she came up with a system to draw the sunset over Lake Balaton with a different colored pencil, selected at random, each evening. We can’t see what she’s drawing here, but it’s possible she’s gearing up for the competitive entrance exam for the Magyar Képzőművészeti Főiskola (Hungarian College of Fine Arts). She recalls being one of the weakest students at her preparatory course, but she would pass the exam with flying colours and enrol in fall 1942. She graduated in 1946 with a degree in art education—to appease her father, she’ll tell you—but no one could stop her from heading to Paris the following year to pursue her one true ambition: becoming an abstract painter.

“First, the number of concentric squares in each set is randomly altered, disrupting the optical vibration of the grid.”

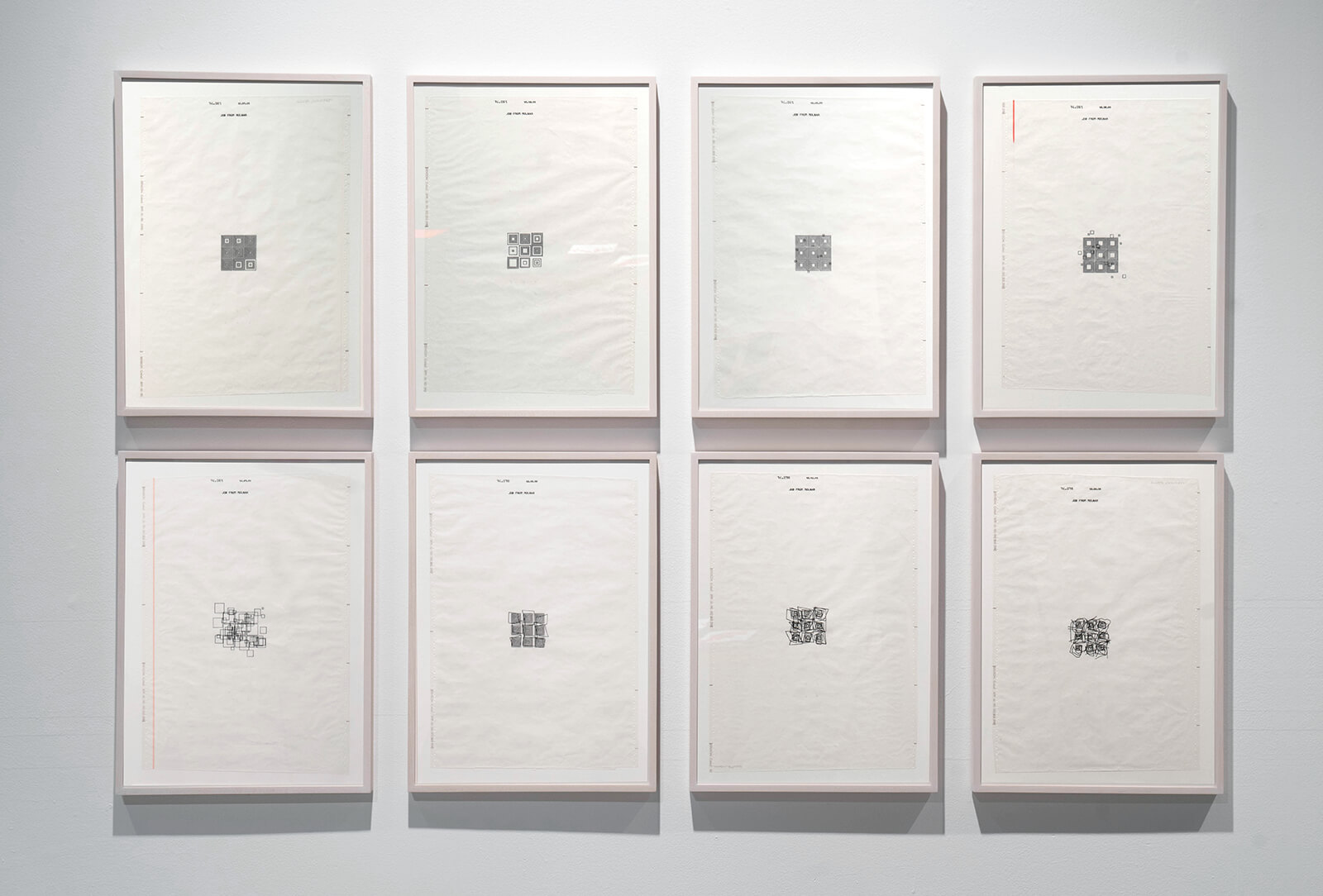

It’s a theme that recurs in many of Vera Molnar’s works, as recognizable as her signature: concentric squares that bend in and out of shape until they become a tangled net of squiggles, no longer recognizable as neat geometric forms. This is the basis of Hommage à Barbaud, the first work from “Variations” that we’ll explore in this dossier. Molnar made this series of eight plotter drawings in 1974, one of her most prolific years.

A matrix of nine sets of seven concentric squares transforms according to three different patterns: first, the number of concentric squares in each set is randomly altered, disrupting the optical vibration of the grid. Then, the concentric squares snap back to the grid, but their central square is randomly displaced, like a fish hanging on to a sea anemone. The rest of the squares follow this pattern until they are completely dislodged from their grid. The grid then resets again, this time transforming by way of the sides of the square being replaced with other geometric forms—curves, diagonal lines. By the final transformation, we have a mess of squiggles, in which we must strain to find the underlying structure.

Molnar’s oeuvre is full of homages to other artists, from Dürer to Monet to Mondrian. But who was Barbaud? Pierre Barbaud (1911–1990) was one of the founders of algorithmic music in France, and a close friend of Molnar and her husband, François. By dedicating a work to Barbaud, Molnar immortalizes the impact of algorithmic music on her work, and on early computer art more broadly.

Though Molnar was friends with other visual artists in Paris, some of them her former art school classmates from Budapest—Simon Hantaï, Judit Reigl, Marta Pán—it was with experimental composers—Pierre Barbaud, Michel Philippot, Janine Charbonnier, Jean-Claude Risset—that she really clicked with. They shared an interest in working with parameters and chance procedures, but in a more systematic way than Dadaist automatism or the neo-Dada of the 1950s. It was from Philippot that Molnar borrowed the term machine imaginaire, her systematic approach to making pictures from around 1958 to 1968. Using basic concepts from combinatorial mathematics and analog ‘randomness generators’ like a roll of dice, Molnar ‘generated’ series of drawings by altering one parameter at a time. Each variation was executed painstakingly by hand.

It was thanks to Barbaud that Molnar accessed her first machine réelle, an actual electronic computer. Barbaud had spent the last decade experimenting at Bull–General Electric in Paris, composing music with their mainframe computer free of charge in exchange for promoting and consulting for the company. Barbaud and Molnar ran in the same circles and, according to Molnar, on the same wavelength, too. They both participated in the 1965 SIGMA festival of contemporary art in Bordeaux, where Barbaud’s Musica d’invenzione was performed alongside pieces by Karlheinz Stockhausen and Iannis Xenakis. In 1968, he invited Molnar to Bull take “his” mainframe for a spin.

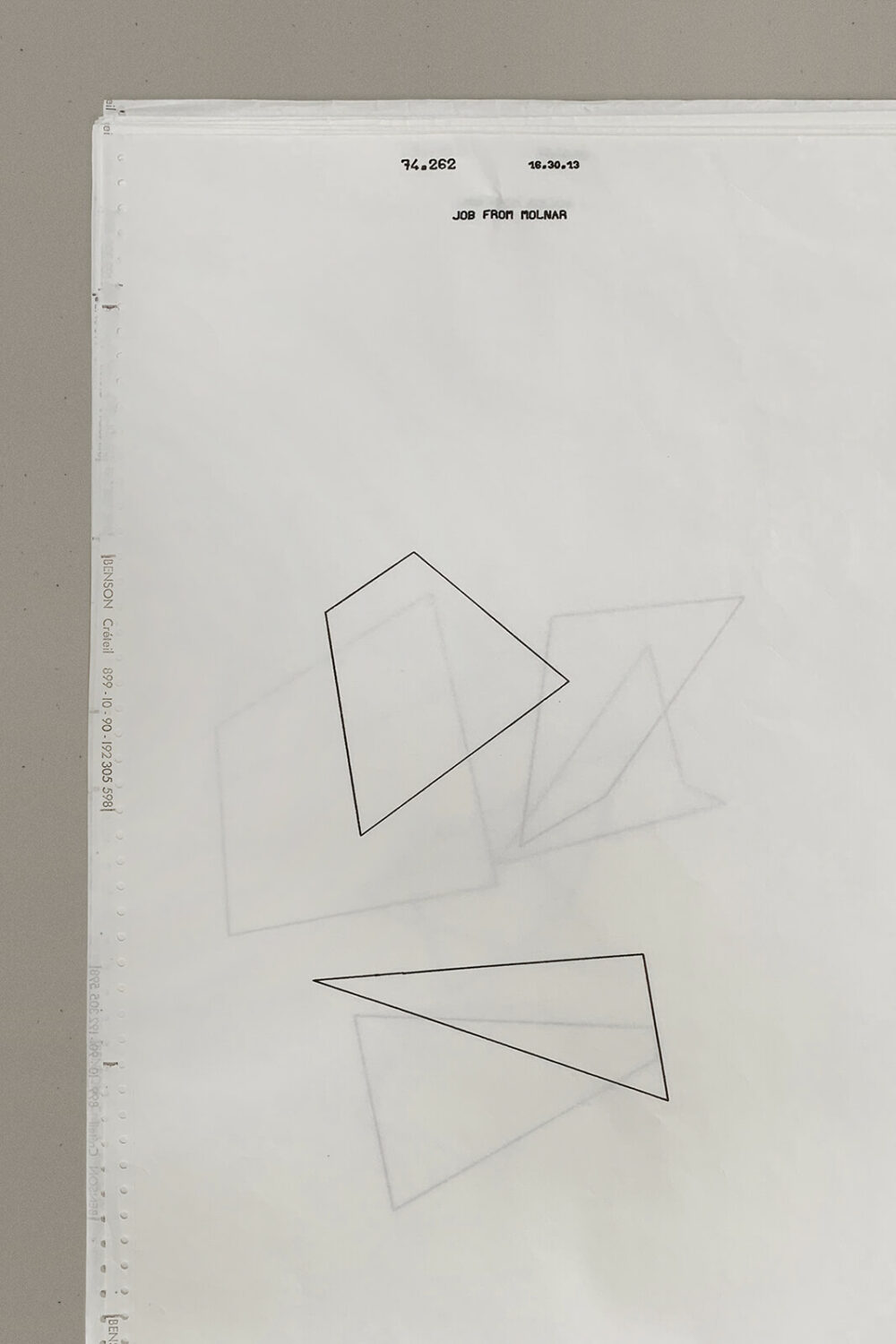

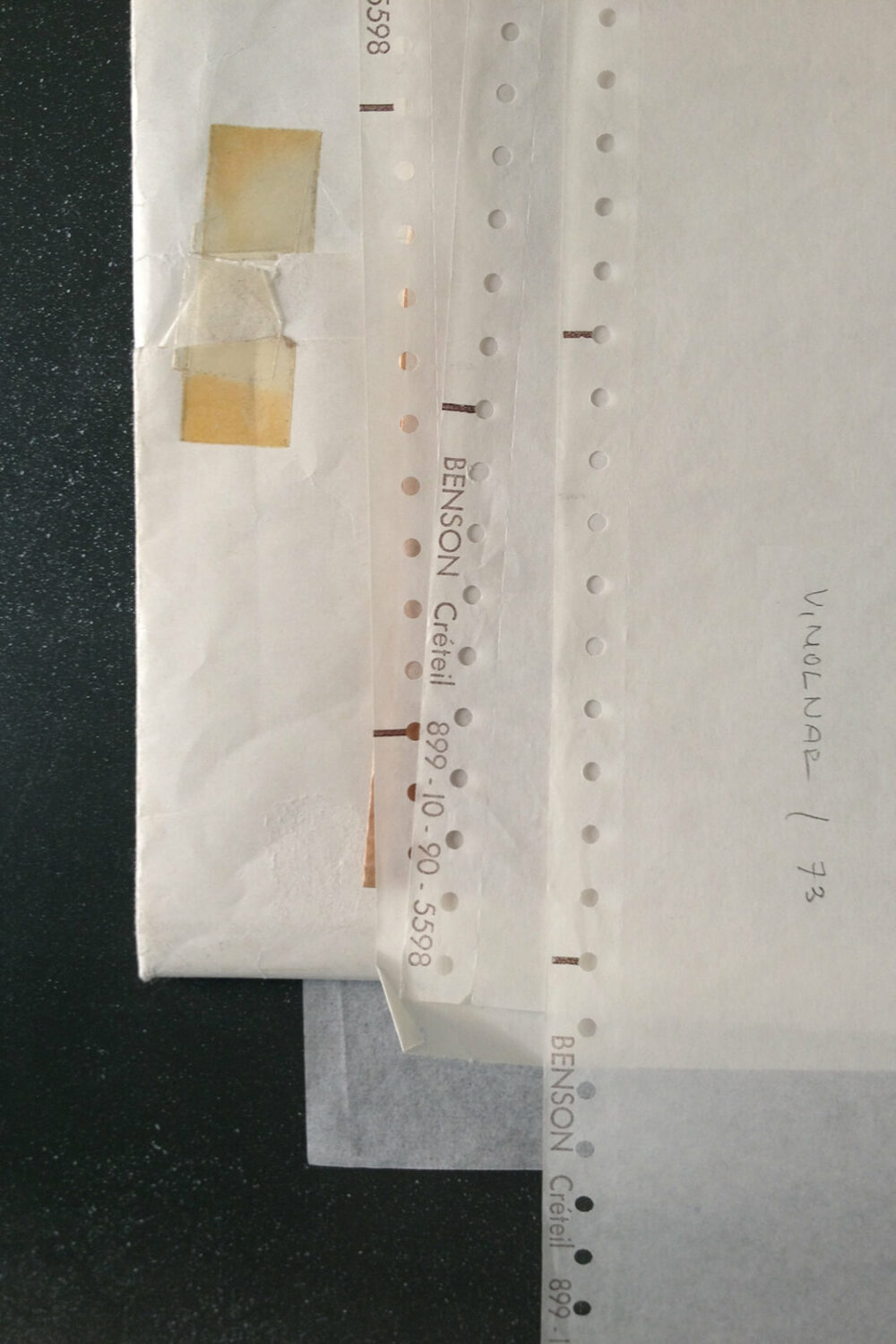

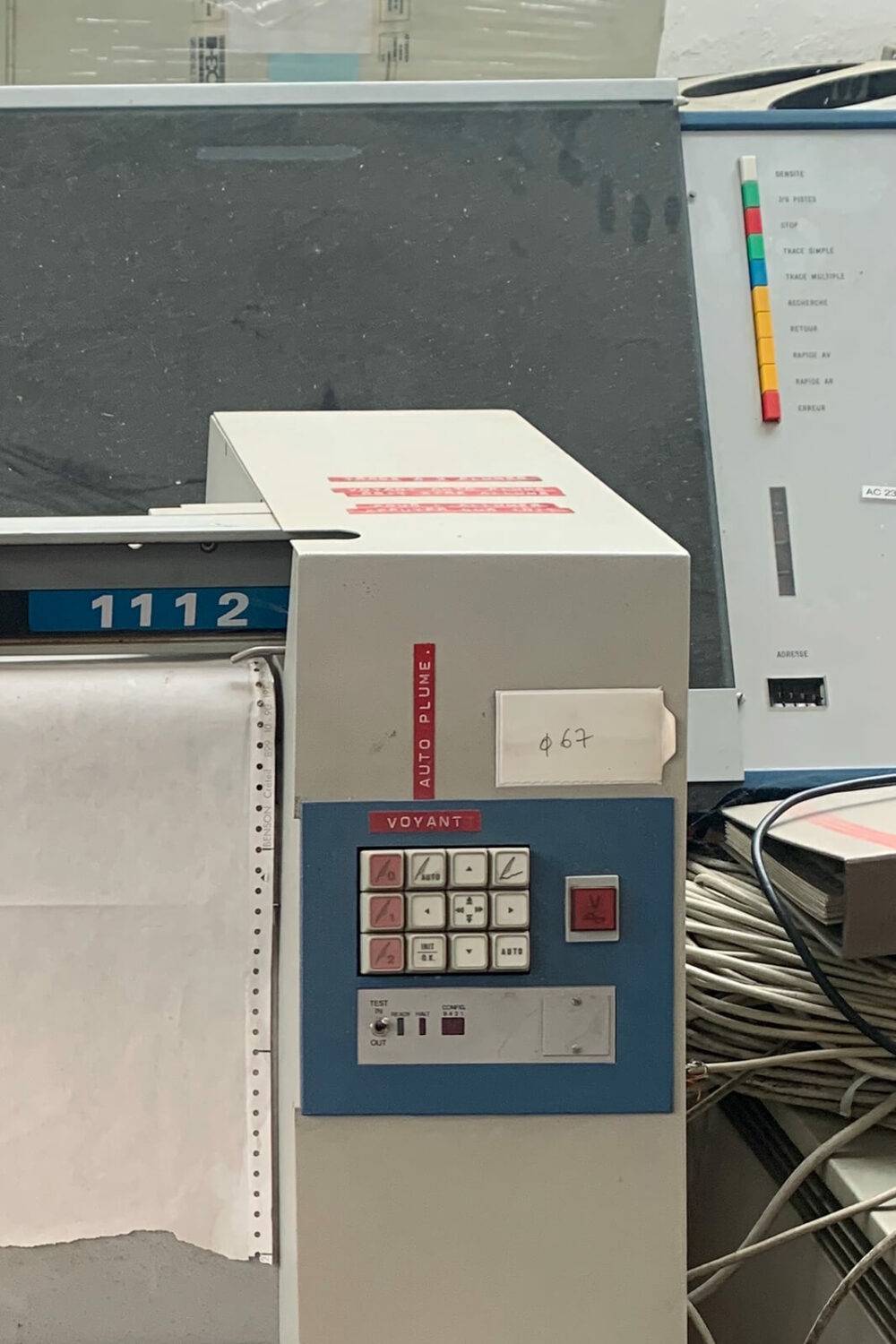

Soon after, Molnar began experimenting at the Sorbonne university computing center in Orsay, just southwest of Paris. She worked there unofficially—clandestinely, she would say—mostly on evenings and weekends. Here, Molnar used an IBM system/370 mainframe computer and a drum plotter manufactured by the French company Benson, a name visible in the margins of most of her 1970s works, just outside the sprocket holes used to feed rolls of paper through the machine. At the top of each page is a timestamp and the words “JOB FROM MOLNAR,” referring to the computer program “Molnart” that she and her husband co-wrote in Fortran.

“So now all of them are going out of place,” Vera Molnar explains the progression from Hommage à Barbaud plot 2 to 3 in her Hungarian mother tongue. “They’re still squares, which is important, still exact squares, but their center is no longer there. It’s scattered.” On May 1, 2022, during her latest research trip to Molnar’s retirement home in Paris, Zsofi Valyi-Nagy asked the generative art pioneer to elaborate on the 1974 series of plotter drawings that is now on view at the Beall Center for Art + Technology. A video recording of their conversation (including English subtitles) is available here.

For collectors and enthusiasts, these marginal details have become all but marginal. But until quite recently, Molnar did not consider them part of the work. In the earliest days, she would carefully cut out her computer graphics, gluing the thin, almost transparent plotter paper to a thicker support. When she started selling her work in the 1990s, she was advised to cover the margins with a passe-partout, so that the image could pass as handmade. Now, Molnar has joked to me, “JOB FROM MOLNAR” is what gives the work market value. “You can forge my signature, but you can’t forge that,” she laughs.

This marginal text allows us to reconstruct the order in which Molnar programmed these images, to develop some understanding of her working process and of the algorithms she used—of which very little documentation remains. In fact, the sequence in which Molnar shows her series—whether in exhibitions or artist’s books—rarely corresponds to the chronological order in which she made them. Barbaud was made over the course of two days, Wednesday, September 18 and Saturday, October 5, 1974. Molnar worked on other series simultaneously, including Out of Square and Love-Story, which also explored twisting and tangling her favorite geometric shape.

Why does it matter that Molnar doesn’t show Barbaud in the order it was made? It may not seem significant, but ultimately the progression from order to disorder in Molnar’s series is artificially constructed. Not only do we only see a small selection of outputs from dozens of variations, but even their sequence is based on subjective choices made by the artist.

It’s a bit ironic, then, that this work is named for Barbaud, because he couldn’t have had a more different approach to algorithms. As Jean-Claude Risset writes, Barbaud refused to “arrange” the results of his compositional programs.1 Molnar also recalls this fundamental difference between their approaches: while Barbaud believed all of his randomly generated results were of equal aesthetic value, Molnar would compare and contrast results until she found the ones she wanted. It was always her—not the program—who had the last word.

This is an age-old question in generative art that remains relevant today. In a recent conversation2 between Casey Reas and Harm van der Dorpel at DAM Projects in Berlin, these artists debated the difference between messing with a program and messing with its results, changing the algorithm or changing the outputs. For some, tinkering is “cheating”—Barbaud certainly would have thought so. But for Molnar, tinkering is possibly the most important creative gesture in her practice. This is something I will continue to explore in the coming weeks.

References:

(1) Risset, Jean-Claude. ‘Une Experimentation Plastique En Actes’. In Véra Molnar: Une Rétrospective, 1942-2012, edited by Sylvain Amic, 28–35. Paris: Bernard Chauveau, 2012.

(2) Casey Reas and Harm van der Dorpel. “A conversation on art, software and NFTs,” DAM Projects, Berlin. April 22, 2022 / a recording of the conversation is available online here

My current fascination in Molnar’s work is comparing the hand-drawn sketches to the automated drawings. The space between them is a world to explore. I can see the seed of an idea start in a sketch or diagram, then be pushed through the process of plotting, tuning, plotting, tuning, etc. The exhibition at the Beall Center was the first time I was able to see the sketches and raw computer plots side by side. It cracked open my understanding of Molnar’s work.

Casey Reas is an American software artist and educator based in Los Angeles. His works have been shown at museums and galleries around the world and are part of private and public collections, including the Centre Georges Pompidou and SFMOMA. Reas is a professor at the University of California, Los Angeles. In 2001, together with Ben Fry, Reas initiated Processing, a widely popular open-source programming language and environment for the visual arts.

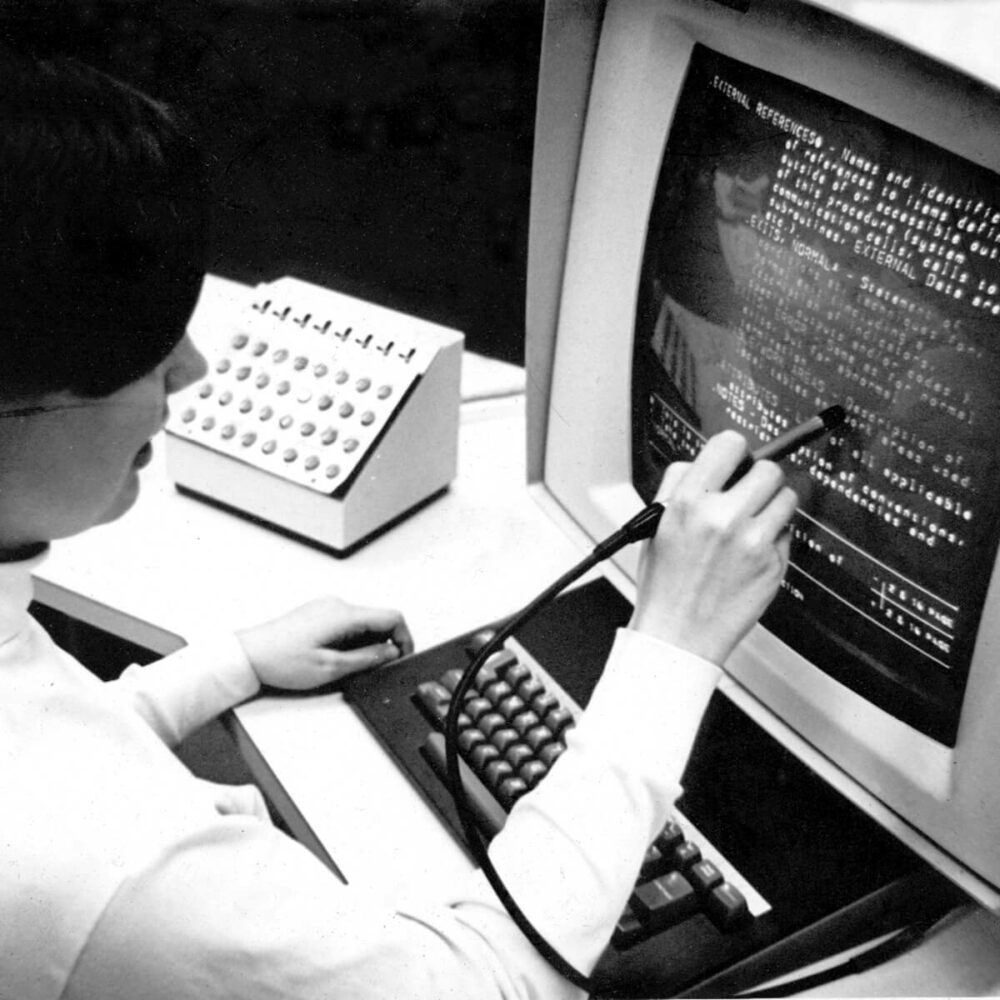

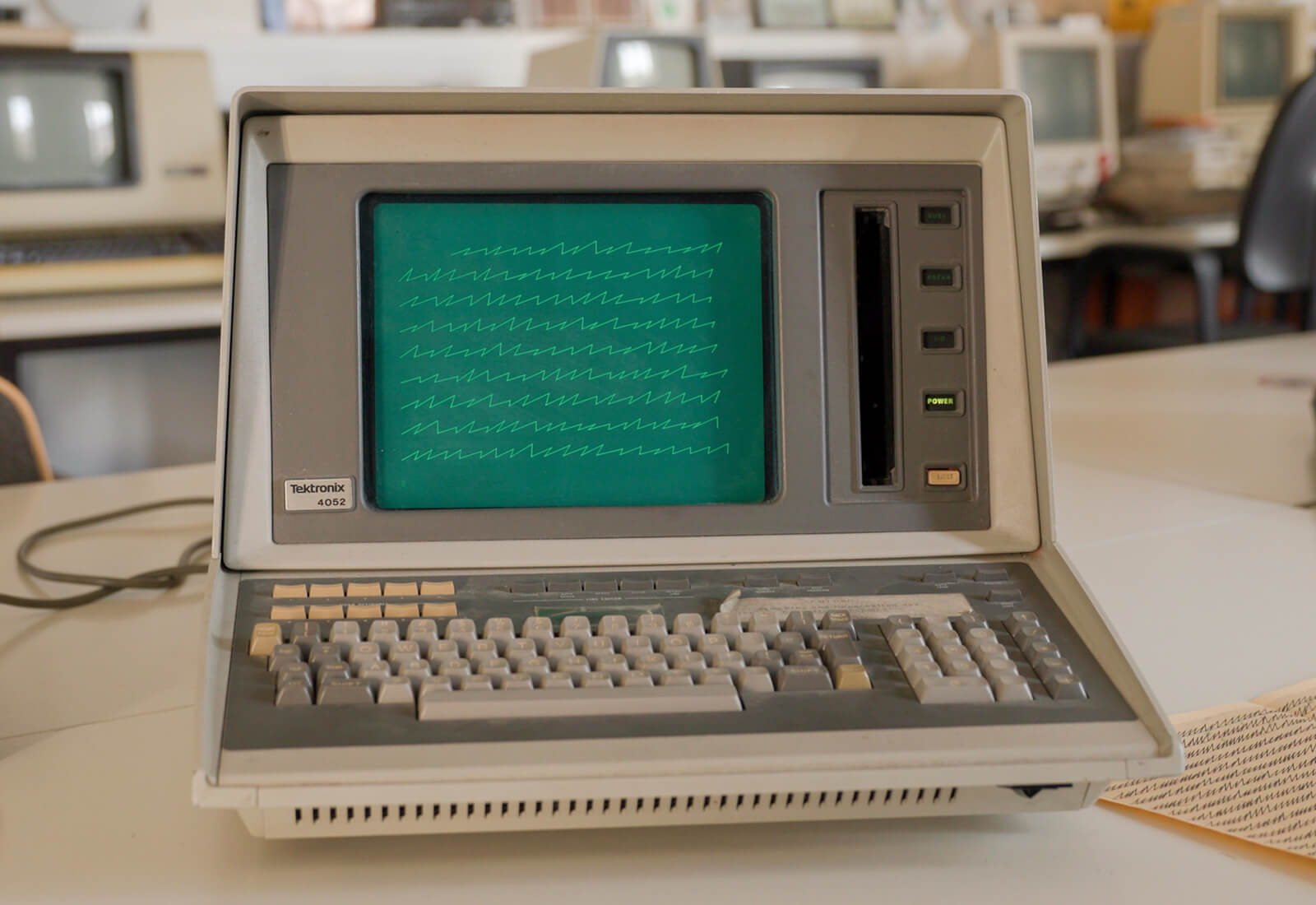

“In the early days, computing was a blind process. Artist gave instructions using punch cards but wouldn’t see the results of their program for hours or even days.”

When we talk about ‘computer art’ from the 1960s and ‘70s, the actual shape and form it took looked quite different from most digital art made today. Nowadays, we’re used to viewing digital artworks—and most other artworks, frankly—on a screen, whether on a phone, laptop, or larger monitor. But this was not yet an option in the early days, when computing was still a blind process. This meant that the artist/programmer gave instructions using punch cards and couldn’t see the results of their program until it was output to paper, hours or even days later. When computer screens became more ubiquitous in the 1970s, they were still only accessible to people in computer labs. Even if an artist made work using a screen—as Vera Molnar did from the early 1970s onward—they still had to make hard copies, for these works simply couldn’t be shown in their native environment. In other words, the images had to be transposed to a more traditional art form: ink on paper.

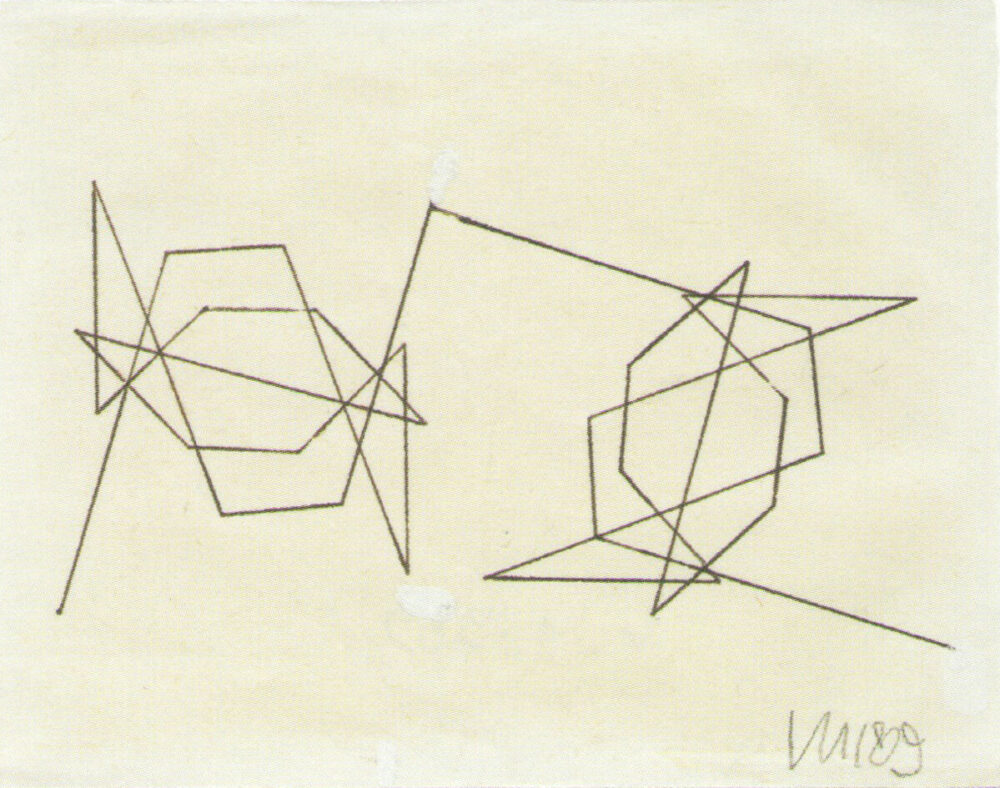

These works-on-paper were not executed by hand, but by the mechanical arm of a plotter.1 Still, they became known as ‘drawings.’ Plotter drawings. For Molnar, this reliance on paper was not necessarily a limitation. It was a way to show continuity with her pre-computer works, which were programmed with the machine imaginaire but executed manually. For her, there was no fundamental difference between working with dice or combinatorial mathematics and working with an IBM system/370 mainframe computer. It was all “painting” to her.2 I want to point out, however, that the plotter allowed for considerable creativity. Molnar experimented with different kind of inks, even making some homespun inks out of beet juice and blood3—the wildest she would ever get—until she settled on a satisfying dark grey tone.

Molnar’s fellow digital art pioneers, including Manfred Mohr, who also worked in Paris, and Frieder Nake, a member of what is now called the Stuttgart school in Germany, also used plotters. But while Mohr and Nake used flatbed plotters, also known as ‘drawing machines,’ Molnar most often used the less glamorous drum plotter. Here’s the fundamental difference: with the flatbed plotter, the paper is stationary and the pen moves in both the x- and y- directionl the operation looks a lot like the human process of drawing, only it’s done by a robot. The drum plotter less so: its pen moves on the x-axis while a roll of paper is fed through in the perpendicular direction. This is why many of Molnar’s works have sprocket holes along the sides. Drum plotter drawings tend to have a more ephemeral quality because the roll mechanism required a very thin, almost transparent paper—by contrast, the flatbed could handle nicer, thicker paper. Perhaps Molnar liked the drafty quality, but my guess is she preferred the drum plotter because it was better suited to serial output: she could plot one variation after another in succession, without having to switch paper.

The ink-on-paper format is perhaps what has allowed art museums to collect this work more extensively than other forms of digital art, as we don’t need to reactivate obsolete technologies to view it. But its deceptive straightforwardness also runs the risk of flattening our understanding of early computational art into a simple process of input and output. I want to suggest we look at the nuances of these ‘drawings’ as an entry point for seeing the complex, iterative, nonlinear, and very hands-on process that was early computing.

References:

(1) See contemporary generative artist Sher Minn Chong’s talk “Recreating Retro Computer Art,” and read her historical overview of plotters here.

(2) See Molnar, Vera. “Toward Aesthetic Guidelines for Paintings with the Aid of a Computer.” Leonardo 8, no. 3 (1975): 185–89. My intention is not to equate painting and drawing, but an exploration of the rich historical relationship between them is outside the scope of this note and will be addressed in my dissertation.

(3) Molnar also told this story to Hans Ulrich Obrist: “Vera Molnar in Conversation with Hans Ulrich Obrist.” In Bookmarks: Revisiting Hungarian Art of the 1960s and 1970s, edited by Hans Ulrich Obrist and András Szánto, 76–87. Koenig Books, 2018.

Anne Spalter is a digital mixed-media artist, founder of the digital fine arts courses at Brown University and The Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) in the 1990s, and author of The Computer in the Visual Arts (1999). Her artistic process explores imagery of the modern landscape. She is currently creating crypto art, with works auctioned by Sotheby’s and Phillips, and featured in the New York Times. She is also co-instigator of the Anne and Michael Spalter Digital Art Collection.

What if Vera had decided thirty years ago that her art wasn’t selling enough or being shown in the right places and had stopped creating? It would have been a tragic loss for all of us. It is a lesson for any artist. I particularly hope that artists who have come to digital art through the NFT world, where everything moves so quickly, take note. Aesthetically my work and Vera’s are usually quite different but I have also been influenced by her commitment to unending quality. I truly can say I’ve never seen a ‘bad’ Vera Molnar.

As an aside, it is a common misunderstanding that artists working with technology gain some extra benefit from using the computer–that it is somehow cheating or making up for a skill gap or some other negative perception. A closer look at their work inevitably disproves this, of course. Artists like Vera Molnár and Manfred Mohr were creating work that looked like their computer work, and that was conceptually related, long before they ever touched a computer.

Collecting pieces from before Vera had access to a computer and through long after she could have brought in a range of new features and tools demonstrates the strength of her specific vision.

“[In the early days] people said I was ruining art, by taking such an artificial approach to something that was so fundamentally human. It felt like I only had enemies. It makes for a good story, though. I very rarely exhibited, very very rarely. But when I did, then these computer drawings, you know the ones that have holes along the sides because they had to roll through the [drum] plotter? At the top you can see the day, the hour, the minute the calculation was made. And I was told to cover this up, to put a passe-partout over it so that all you could see was the drawing. And I had to sign it, by hand. But now, that [timestamp] is all the collectors care about. Anyone could forge my signature but that, no one can forge that. They only want drawings where the computer is visible. The paper with the holes in it? They don’t use a passe-partout anymore. They frame it with the holes showing!”

Vera Molnar to Zsofi Valyi-Nagy (translated from Hungarian), Paris Oct 31, 2019

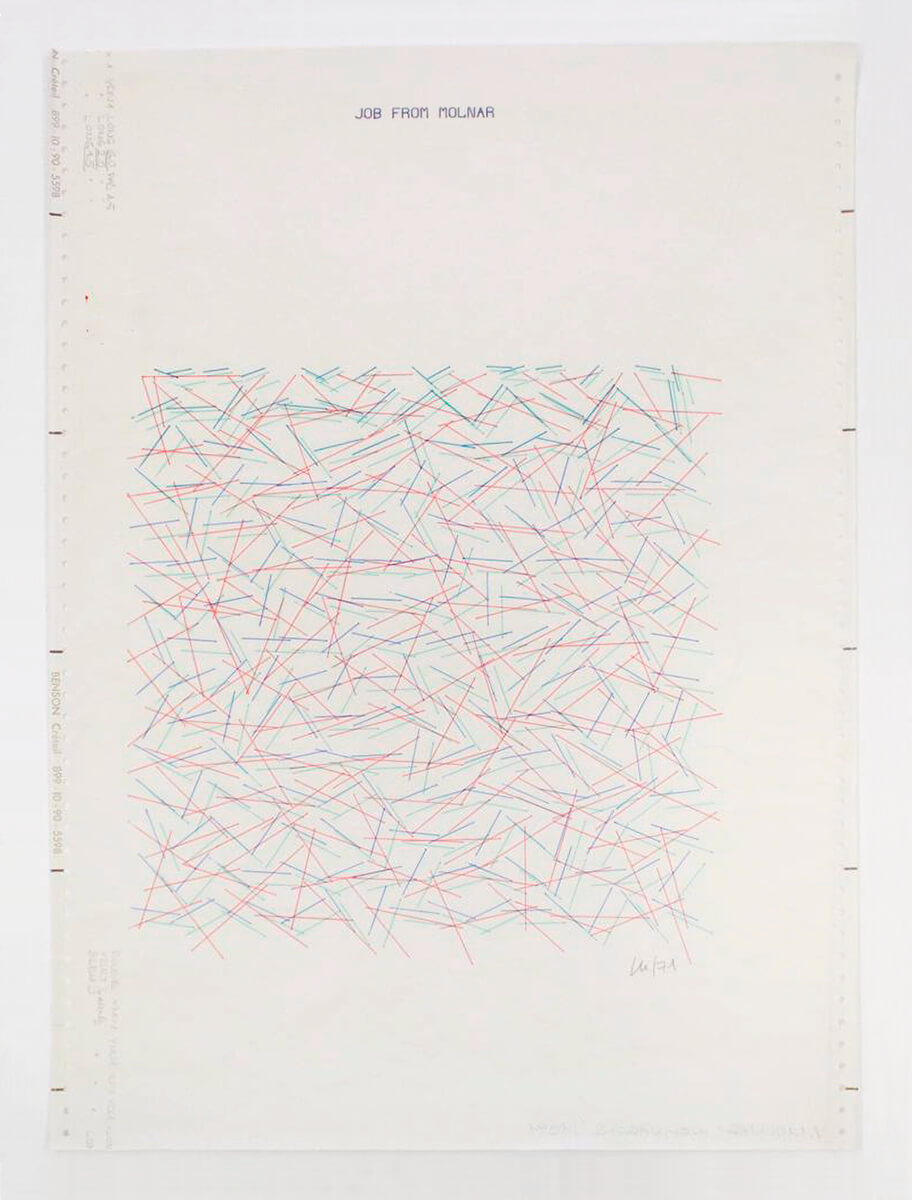

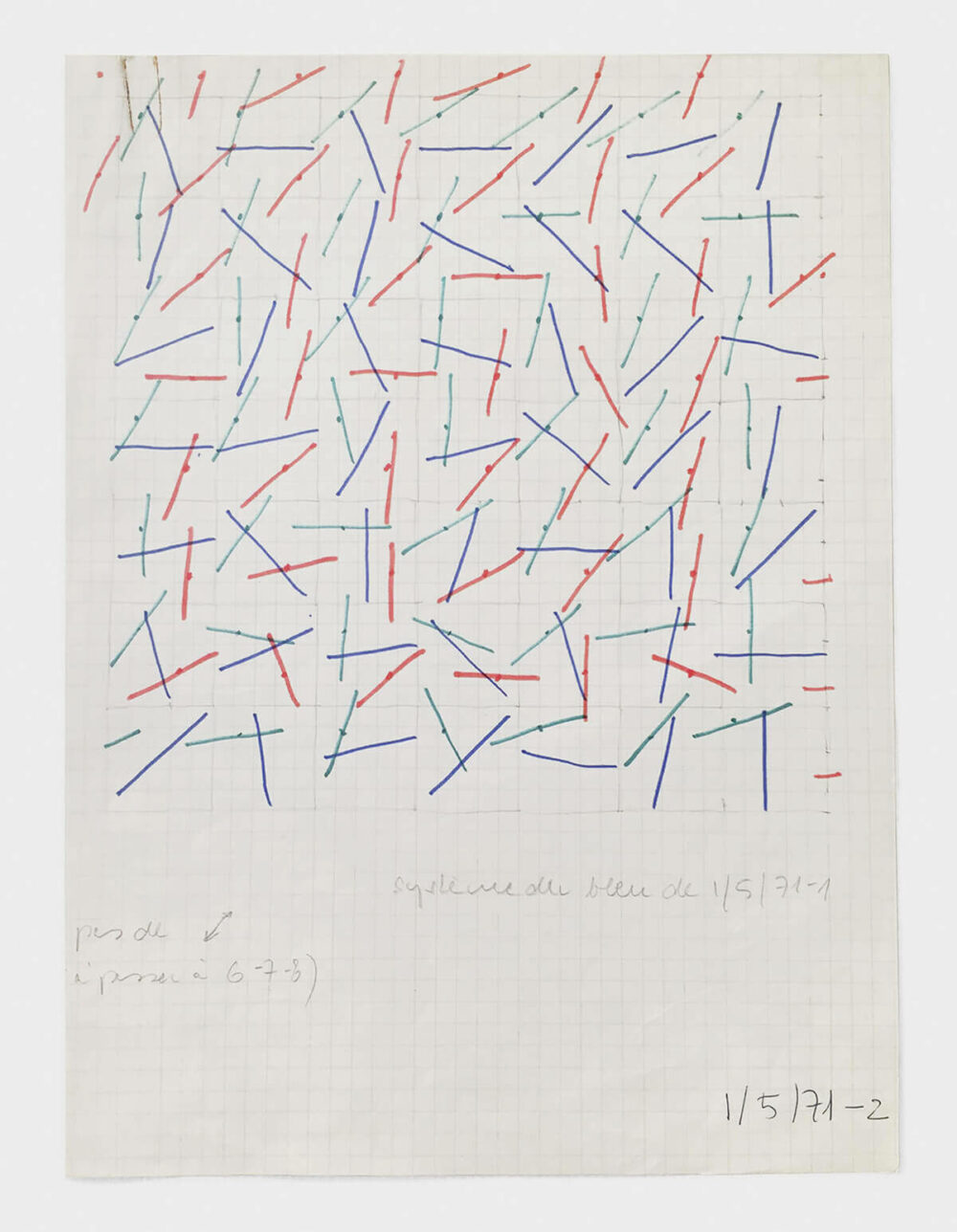

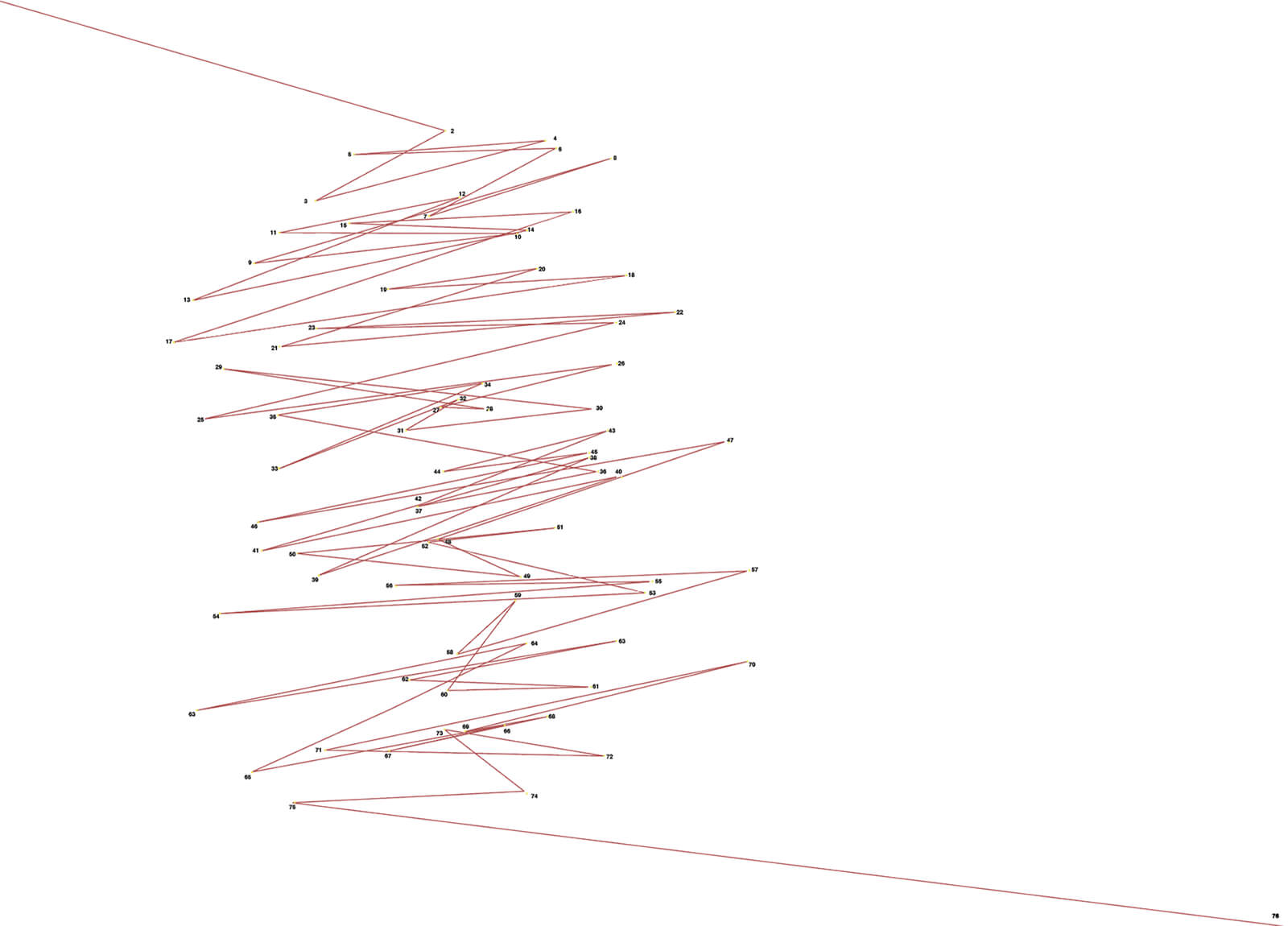

“In this plotter drawing, we see line segments in red, green, and blue—the three additive primary colours—scattered over a square surface area like a game of pick-up sticks.”

Vera Molnar loves colour as much as the next painter, but we rarely see colour in her plotter drawings from the 1970s. Much like the juice and blood she experimented with, the marks of coloured plotter pens were more ephemeral — highly light sensitive and not designed to last. In this plotter drawing Inclinaisons from 1971, however, we see line segments in red, green, and blue — the three additive primary colours — scattered over a square surface area like a game of pick-up sticks.

Inclinaisons, like its English cognate inclination, refers to a tilt, a line that runs oblique to the horizontal plane. The word might be used to describe the lines in a graph that a scientist would output to paper using the same tools as Molnar. But Molnar’s ‘figure’ seems to mock the orderliness of scientific data. Her lines lead to nowhere, point to nothing. Their random distribution produces a visual rhythm, given more texture by the colour variations. At points, the colours overlap, creating teals, purples, and browns that anchor the eye, if only for a moment.

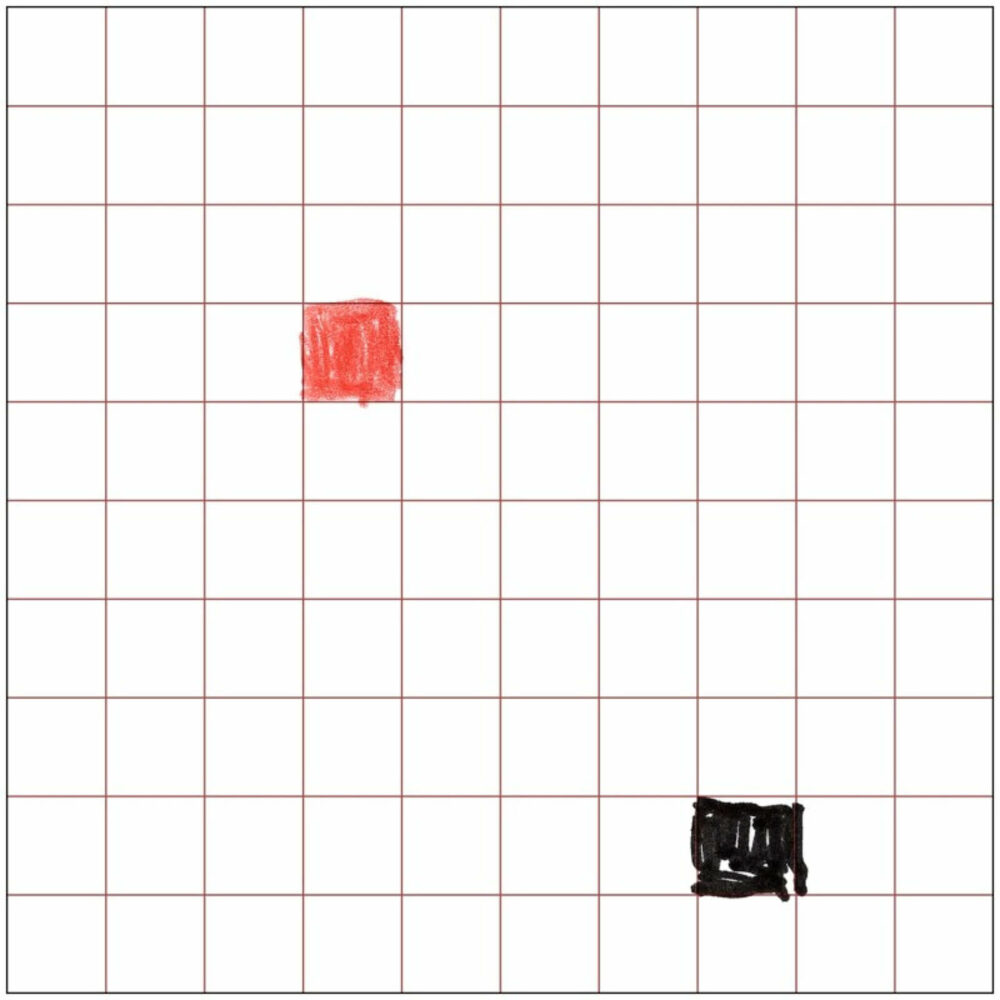

While Molnar did not begin her Journaux Intimes until 1976, she did hang onto her sketches for this work, which are framed alongside the plotter drawing at the Beall Center (the Spalter collection also includes two studies from 1969 and one from 1972). Of the two in this show, one is more obviously handmade, with red, green, and blue marks drawn with marker in a 7 x 7 grid structure, delineated by the artist herself in graphite on graph paper. Its wavering lines suggest that she drew the grid freehand. The other study is on tracing paper, the delicacy of which throws the different line qualities into sharp contrast: the thin blue marker appearing crisp alongside the thicker, runnier red and green that she accidentally smudged. Neither study, however, is identical to the plotter drawing. While they demonstrate that Molnar did work out ideas on paper, they do not establish a strict, linear relationship between hand-drawn sketch and computer-generated final product.

In fact, Molnar’s process involved a constant dance back and forth between paper and computer, between pencil and keyboard, and between images and alphanumeric commands. She worked — and continues to work — in a series of translations and transpositions across media.

In 1974, Molnar came up with a term to describe her way of working. Writing for the journal Leonardo, she described her “conversational” method, always leaving the scare quotes around conversational.1 Why? My guess is that she borrowed the term from French computing discourse, where conversationnel referred to interactive computing. While blind computing involved a significant time delay between submitting instructions and receiving results, interactive computing happened in real-time. The site of interactivity was the computer screen, which served as an interface between the user and the computer. In fact, the introduction of the interface is when the user, in our contemporary conception of the term, was born. I argue in my dissertation that the advent of interactivity was the most significant milestone in Molnar’s career, though it’s been overlooked in both studies of her work and in the history of computing more broadly.2 When I asked her about the screen in our very first conversation, a shaky phone call in August 2017, I could hear her beaming as she said, “The IBM 2250!” She recalled her first time using the screen like a sort of rebirth, akin to moving to Paris at age 23. While I still don’t know for sure what year she first encountered the IBM 2250 (it was released in 1964, but there was usually a delay getting hardware to Western Europe; Molnar does not mention it in her writing until 1973), she remembers it with the kind of fondness usually reserved for an old friend.

Output on paper: Vera Molnar, plotter drawing from the series Inclinaisons, 1974, about 52 x 35 cm (collection of the artist)

In 2018, leafing through a box of archival materials at the home of Molnar expert Vincent Baby, I stumbled upon these unmarked, black-and-white photographs of a computer screen. It wasn’t until 2020 that I found their plotter drawing counterparts at the artist’s studio, labeled, again, Inclinaisons, dated 1974. Another thread resurfacing in the Molnar textile. While these photos were never exhibited in an art context, they seemed to capture a moment Molnar did not want to forget.

So what was the conversational method? It employed not only a mainframe computer, but two key peripheral devices: the plotter and the CRT display screen, an IBM 2250 vector graphics display. She embraced the screen like few of her contemporaries did. Instead of waiting for the results of her program to be output to paper, she “[made] parameter changes quickly while viewing the images on the CRT screen.”3 This was not just about hardware. It also raises a fundamental question about process. Molnar’s results were emphatically not predetermined; they were always contingent on her subjective decisions.

Molnar’s text subtly points to the ways in which her method differed from others: “Whereas they begin with an initial set of rules (a grammar) specifying the way parameters are to be varied, I try to elaborate the rules as a work develops.” Her words recall debates about ‘tinkering’ that remain relevant to generative art today. Is it right for artist-programmers to mess with their results, their algorithms, or their programs? At what point do we call it ‘cheating’?

Some might say that Molnar cheated with the computer, an accusation I don’t think would upset her terribly. Maybe she did, depending on how you look at it. If you ask me, I’ll say that she was simply insistent on having the last word. Though I’m skeptical of her insistence that the computer was merely a tool for her, it’s true that Molnar never let it subsume her role as an artist.

References:

(1) Molnar, Vera. “Toward Aesthetic Guidelines for Paintings with the Aid of a Computer.” Leonardo 8, no. 3 (1975): 185–89. The text appeared in English. Molnar submitted the manuscript, written in French, to Malina in May 1974.

(2) Recent scholarship on early computer graphics largely comes from architectural history and media studies. See Matthew Allen, “Representing Computer-Aided Design: Screenshots and the Interactive Computer circa 1960,” Perspectives on Science 24, no. 6 (2016): 637–68; Jacob Gaboury, “The Random-Access Image: Memory and the History of the Computer Screen,” Grey Room, no. 70 (2018): 24–53; and Bernard Dionysius Geoghegan, “An Ecology of Operations: Vigilance, Radar, and the Birth of the Computer Screen,” Representations, 2019, 86.

For earlier historicizations of interactivity, see sociologist Thierry Bardini’s Bootstrapping: Douglas Engelbart, Coevolution, and the Origins of Personal Computing (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2000) and interaction and videogame designer Brenda Laurel’s Computers as Theatre, Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Pub. Co., 1993.

(3) Molnar, “Toward Aesthetic Guidelines,” 187.

(4) ibid. The word “grammar” was included on the suggestion of Leonardo editor Frank Malina.

I’ve always loved squares and cubes, with their symmetry and stability and perfect rationality. The history of early 20th century modern art is filled with them, from Malevich’s Black Squares to Mondrian’s grids of primary colors and Albers’ colour studies. Although every artist might decide to use these shapes for different reasons, ultimately, they became a symbol of the almost scientific pursuit of “progress’ in art—as if art itself could be made as perfectly rational as geometry or industrial mass-manufacturing. But the square and cube are always haunted by their negation—by the threat of entropic dissolution or the specter of the chaos that lies beyond their borders. In the 1960s and 1970s, postminimalist artists made squares that literally seemed on the verge of collapse (signaling a preference for the messiness of reality over the perfection of abstract ideals), such as Richard Serra’s One Ton Prop (House of Cards) or Gordon Matta-Clark’s Splitting. I love these works, but I’m especially drawn to artists like Julio Le Parc and Vera Molnar, who embraced industrial and technological materials and processes to produce their own corrupted squares, essentially challenging the modernist cult of rationality with its own tools. When I look at Molnar’s many ‘transformations’ of the square, I see not only the automation of composition through algorithms, but also a celebration of the everyday beauty of the vitally imperfect, and even a kind of political statement about the values we encode in our technologies.

Tina Rivers Ryan is an art historian specializing in modern and contemporary art, with a focus on the uses of new media technologies since the 1960s. An Assistant Curator at Buffalo AKG Art Museum since 2017, her recent exhibition “Difference Machines: Technology and Identity in Contemporary Art“ was awarded the 2022 Award of Excellence by the Association of Art Museum Curators. Ryan’s writing has been commissioned by museums including the Walker Art Center, the Dia, and HangarBicocca; and she regularly writes about exhibitions and (more recently) the rise of NFTs for magazines such as Artforum, Art in America, and ArtReview.

“Close friend François Morellet would refer to Vera and husband François Molnar as un peintre à deux têtes, a two-headed painter.”

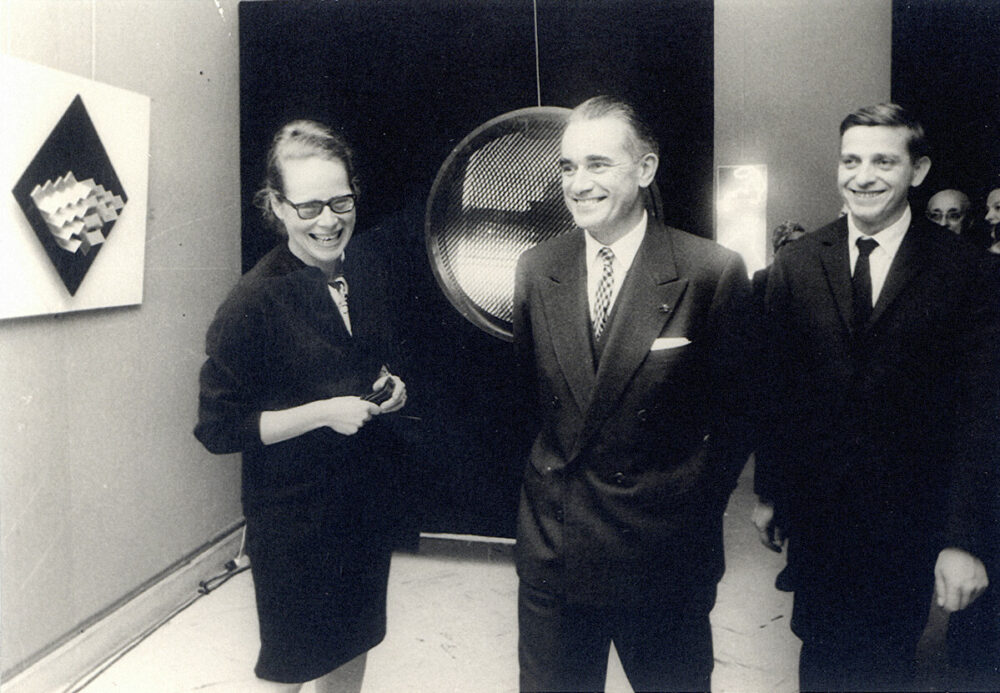

During their first decade in Paris, Vera and her husband François Molnar often made paintings and collages collaboratively. Their close friend François Morellet, who they met in 1957, would refer to them as un peintre à deux têtes, a two-headed painter. In Vera’s words, they had “two optics, each with their own ideas of variations.”1

Their collaborations usually took place at the planning stage of a painting or large-scale collage. The Molnars would pin paper cutouts to the wall of their home/studio, and alternately make modifications until they agreed that the composition was finished. Then, Vera would do the painting and gluing, since of the two of them she was more enthusiastic about the materiality of making pictures—the smell of turpentine, the sound of graphite sliding along a sheet of paper.

Not all of Vera’s 1950s works were made with her husband. In a photo from 1954, she sits at her desk against a tall Parisian window, under a collage titled Douze Rectangles that is now held at the Musée de Grenoble along with many of their co-signed canvases. This one bears only her signature. Without the signatures, it’s nearly impossible to tell the solo and collaborative works apart. Not only did the couple paint according to a shared ideology, very much in current with the postwar Concrete Art movement, but this very ideology emphasized a ‘rational’ methodology that de-emphasized individual authorship.

The Molnars didn’t follow this path for long. After co-founding the Centre de Recherche de l’art Visuel (CRAV), later known as GRAV, in July 1960, the couple left the group only four months later, citing a fundamental disagreement over the definition of ‘research.’2 They made their last co-signed canvas, Effet esthétique de l’inversion des fonctions par la fluctuation de l’attention, in 1960, exhibiting it in Max Bill’s landmark exhibition “Konkrete Kunst” in Zurich that same year. Then, François Molnar ‘quit’ art, turning his attention to scientific research in perceptual psychology and experimental aesthetics. I argue in my dissertation, however, that the Molnars’ collaborations did not really end there. Rather, they took on a different shape. For the next three decades, until François’s death in 1993, the couple remained each other’s primary interlocutors, Vera’s painting influencing François’ research and vice versa.

References:

(1) Deiss, Amely, and Vincent Baby. “Entretien avec Véra Molnar.” In Véra Molnar: Une Rétrospective, 1942-2012, edited by Sylvain Amic, 15–19. Couleurs contemporaines. Paris: Chauveau, 2012, 18.

(2) François Molnar, “Lettre de démission / Letter of resignation, 30.11.1960,” in GRAV, Groupe de recherche d’art visuel, 1960-1968: stratégies de participation: Horacio Garcia Rossi, Julio Le Parc, François Morellet, Francisco Sobrino, Joël Stein Yvaral: 7 juin-6 septembre 1998, Magasin—Centre d’art contemporain de Grenoble, ed. Yves Aupetitallot (Grenoble: Le Magasin, 1998), 59–61.

This letter suggests that the disagreement was primarily François’ and that Vera left in solidarity, along with the artist Servanes.

Iskra Velitchkova is a Bulgarian self-taught computational artist based in Madrid. She focuses her work on generative art but she is interested and inspired by all kinds of interactions between humans and machines. With a background in data visualization, first with her own studio and as a member of different scientific teams, Velitchkova grounds her work in understanding how we can design and use technology to better understand ourselves.

Molnar’s work, in particular, has a very special effect on me. Her works speak for themselves as those silent people who are listened to in the crowd. They are subtle, elegant, minimal and complex at the same time. I don’t know when I first found out about her, but what is exciting and beautiful to see is that recently—thanks to the Spalter Collection or the voice of Jason Bailey, among others—she has been broadly recognized as one of the key figures of the history of computational art.

I vividly remember the auction. After a few days in New York, we were back at home and it felt like a celebration. No matter what happened, I just wanted to enjoy the moment. We decided to bid on Molnar’s piece, but earnestly, without any expectation that we could compete with the big collectors. At the end, in the last moment, we realized we had placed the highest bid; I had just sold my piece, so it felt like we had to win at all costs. It was such a unique moment to get a historical piece from her—and we did! We celebrated the purchase with a bottle of champagne we bought from Sotheby’s and then some friends joined us.

I cannot say how it feels to us having her piece at home, because it’s not yet here! But we definitely know where it will be placed. Immediately in front of people as they enter through the front door. Vera will be chairing the living room.

Q: Fairly recently, I reluctantly joined Twitter, and I stayed for your plotter drawings, which I encountered thanks to an algorithm. Not only are the works elegant, intricate, and graceful, but it was exciting to see the familiar movement of the plotter pen, in the form of a gif or a video clip, something so physically material interspersed with the hyper-digital generative art on my feed. Could you tell me more about your work with plotters, and how it relates to or is distinct from your digital generative art practice?

A: The plotter work is completely different from my digital work. A few years ago, when I decided to quit my job and begin my journey in art, I spent a year entirely focused on exploring where I wanted to go. I had the clear vision that whatever I would do, it would be connected to and based on technology, but I needed to link to something physical. My work—my life—is always based on roots, connections, and relationships. After several months of theoretical explorations I decided to take action. I bought a pottery wheel without knowing what I was going to do with it, but I started to learn about clay and porcelain. I was so intrigued by how to bring my algorithms into something that is pure and simple as clay. Then I bought a plotter and I started to explore how to use it to paint on the irregular surface. And I just fell in love with it and I forgot my original mission! Both artisan activities allow me to escape from the normal perception of time. The experimentation became the work itself.

Generative art has something very different from other art movements. In generative art we explore with a huge lack of control. It sometimes feels like there is some kind of a divine power on the other side. We guide the machine but then the machine gives us an inhuman result—and sometimes it’s cryptic as to how it is made. One way I like to explore this complexity is plotting the output. A composition appears on screen in less than a second, but once you plot it, the course of time changes. You can observe for hours and see the rationale behind the drawing—you begin to understand it. If you use this as a process, the plotter feels like a translator—a teacher—I create a piece, I plot it, I understand it, and then I go back to the computer with stronger directions. And this is why I love to film the process and share it—it feels like a story about time and a dialogue between me and the machine.

I like to compare this process to photography, which I have loved since I was a child. After training the eye for many years, I decided to dive more into the theory of it and learn how the camera actually works. Once I started to explore with the digital camera I realized I didn’t understand anything (the light, the shutter speed, etc.), so I decided to buy a film-based camera. First of all there is huge friction, since you are constrained to a roll, you have to be intentional about each photograph and then develop it. This period opened me to the need to always get to the roots of any activity I do. The plotter is my analogue camera now. You cannot get crazy if you don’t master your tools.

Q: Your website opens with a proposition: “I don’t think we should make technology more human, I believe that we have to push technology forward to understand us better.” This reminds me of Vera Molnar’s attitude toward computing technology; from the beginning, when she was met with criticism for using such a ‘cold’ machine to make art, she argued that using the computer could actually bring us closer to the human aspects of creativity. In what ways have systems, algorithms, and neural networks helped you understand yourself better, as an artist and/or as a human?

A: After many years working and dealing with data, at some point I realized I was more interested in the algorithms themselves than in the data. I had the chance to work with very talented people from whom I learned a lot about the science behind our technological processes today. Techniques like Deep Learning opened to me a new world of possibilities to map our world. Understanding how machines trace our behaviours and classify them into several dimensions (not just the three we are used to), understanding how we are establishing distances between ourselves and our context (which book the algorithm recommends to me, which song, which person). it’s something bigger than what we used to think. It’s about finding a new kind of distance, which is not physical distance but it is still a distance.

I mean, formalizing these connections between us and things we belong to, the people we love or potentially do, it feels like somehow, an unprecedented encyclopedia about ourselves. Even if we are far from having true intelligent machines, we are building the basis for that. I really don’t think all this work has to be focused on a mission to replicate human identity—there are enough people on Earth—but I think technology is how we unlock mysteries. We are limited in our perceptions, we can not even understand our own feelings sometimes. We tend to be more rational because we have learned this is the way we deal with complicated situations; but we are much more than a brain and our emotional side—our passions—guide us ultimately. This is why, my utopian dream, is that after a long history of human explorations and deviations, our ultimate goal is to process who we are and what makes us human. And if machines can help with that, it would be a welcome change.

“Why only look at exhibition history as evidence of an artist showing their work? Instead, I suggest we broaden this idea of showing work to sharing work.”

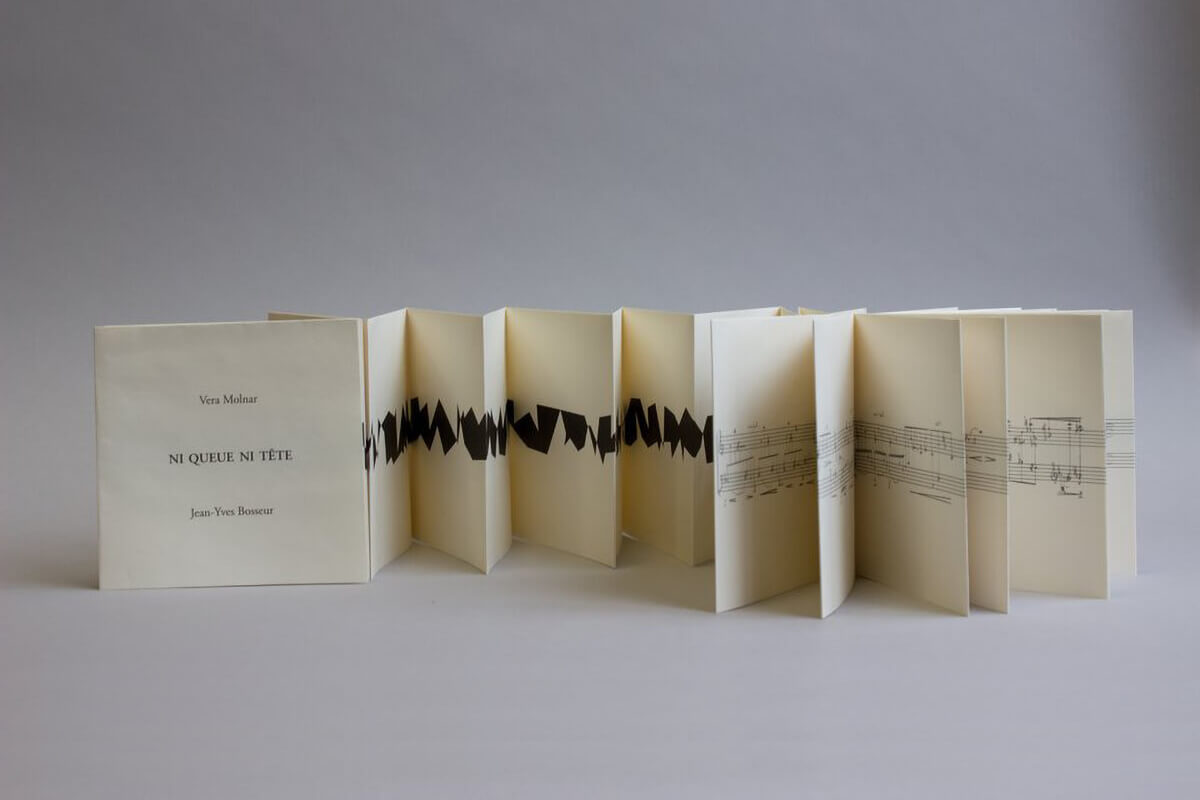

A collaborative project bringing together a visual work by Molnar, a composition and text by Jean-Yves Bosseur, and performance by Pascal Dubreuil. Edited and published by Couleurs Contemporaines and Bernard Chauveau. The work is housed in a custom-made portfolio box containing Molnar’s six meter long folded artwork, printed on 90-gram Acroprint Edizioni paper; a musical score partition booklet by Bosseur; and a CD of Dubreuil’s performance.

The usual narrative around Vera Molnar’s work is that she didn’t exhibit her work until the mid-1970s, and even then, only sparingly. It is true that she didn’t focus on exhibiting and building relationships with galleries until the 1990s, especially after her husband passed away. Whether her husband was the reason why she didn’t exhibit much before this is up for debate, but let’s save that for another day. Instead, I want to ask a different question: why only look at exhibition history as evidence of an artist showing their work? In today’s research note, I suggest we broaden this idea of showing work to sharing work. In other words, what were the more informal contexts in which Molnar shared her images or her ideas? We are going to peek at some of the alternative spaces in which Molnar’s work reached audiences: informal research groups, festivals, academic journals and conferences, art magazines, and self-published artist’s books.

In 1967, a year before she first accessed the electronic computer with the help of Pierre Barbaud, the Molnars co-founded the group Art et informatique (Art and computing) at l’Institut d’esthétique et des sciences de l’art (Institute for aesthetics and the science of art) at the Sorbonne in Paris, where François Molnar worked as a researcher. The group mainly consisted of music composers, including Barbaud and Janine Charbonnier, but also included poets like Jacques Mayer, who wrote in the parameter-driven Oulipo style made famous by novelist George Perec. Vera Molnar was the only painter in the group; in fact, despite their near-identical names, Art et Informatique would have little contact with the Groupe Art et Informatique de Vincennes (GAIV), formed at the University of Vincennes across town in 1969. As Molnar recalls, the Sorbonne group met weekly to discuss their works-in-progress and the more theoretical stakes of computing for the field of aesthetics. As these conversations gained momentum, the members of Art et informatique shared their work with broader audiences at events like the SIGMA festival in Bordeaux, which showcased contemporary intersections of art and science. While François Molnar had already participated in the first edition of SIGMA in 1965, co-organized by Michel Philippot (the composer who inspired Vera Molnar’s ‘machine imaginaire’) and Abraham Moles (who developed the field of ‘information aesthetics’ in France), Vera Molnar did not formally participate in the festival until 1973, when the festival was titled “Art et ordinateur” (Art and computer). Here, she gave a talk titled “L’Oeil qui pense (The thinking eye),” which she borrowed from the notebooks of Paul Klee. She also designed the festival posters as well as the catalogue for the exhibition “Contact,” in which her computer plotter drawings were shown alongside computer graphics made by Herbert W. Franke, Kenneth Knowlton, Manfred Mohr, Frieder Nake, and the GAIV artists, among many others.

(2) Vera Molnar’s article in Leonardo, Vol. 8, No. 3 (1975: 185-189) (Molnar archives)

(3) Vera Molnar’s work reproduced in Abraham Moles’ book Art et ordinateur (Casterman, 1971), likely the earliest circulation of Molnar’s images in print. Note that the image reproduced (left) is not a plotter drawing, but a collage based on a computer-generated image.

It was in these liminal spaces between art and science that Vera Molnar’s work first reached an international audience beyond the Sorbonne computer lab. Throughout the 1970s, her images circulated in American periodicals including Computers and Automation, (later renamed Computers and People) and Computer Graphics. These black-and-white reproductions were flanked by technical specs––what machines she used to make them––as well as short anecdotes from the artist. Molnar also penned longer articles for journals, perhaps the most widely distributed being the Franco-American journal Leonardo, edited by artist/engineer Frank Malina, which was published in English and thus had a wide Anglo-American readership. In response to her 1975 text “Toward Aesthetic Guidelines for Paintings with the Aid of a Computer,” Molnar received quite a bit of fan mail. She replied by mailing out photocopies of her livrimages, her artists’ books, including Love-Story and Out of Square (both 1974), which she referred to in English as “computer picture books,” until she ran out. Molnar self-published her early livrimages, cutting and pasting their accordion folds by hand, only later collaborating with printmakers and publishers (mostly notably Bernard Chauveau) to make higher-quality artist’s books, two of which are included in the Beall exhibition (Ni Queue ni tête, 2014 and Six millions sept cent soixante-cinq mille deux cent une Sainte-Victoire, 2012).

I don’t mean to suggest that giving an artist’s talk at an academic conference, or publishing computer graphics in a specialist journal, are the same as gaining art-world recognition. Of course, these are quite different kinds of achievements. However, I want to suggest that these alternative modes of ‘exhibiting’ might have done things for Molnar’s work that exhibiting in traditional art venues couldn’t have. For one, they brought her work to an international audience, one that was perhaps more open-minded than the traditional museum-goer when it came to determining what counts as art and what doesn’t. Moreover, by printing her words alongside reproductions of her work, these print publications in particular worked to level the hierarchy between the artist’s theory and practice, placing them on equal footing. On the one hand, we could say Molnar had to be her own critic in the absence of art-world attention. But on the other hand, this gave her an advantage, as these venues provided more space for context and the artist’s own voice, allowing her to direct her own narrative.

(1) For more on Molnar’s Livrimages, see Vincent Baby’s text “Les Livrimages” (1999, in French)

“I belong to that generation where the first things I made with computers … there was no screen. If you can imagine that. You couldn’t see what you were doing. You would see [the results] the next day, or three days later, and then you’d say … that’s not what I wanted! When the screen appeared, it completely changed my life. It was like moving to Paris all over again, that’s how exciting it was…. I had this feeling that this was invented for me. This was an academic research institute, so people didn’t really care how the graphics looked, or what graphics even were, really. But that is all I cared about. I realized very quickly that the computer screen was the thing for me.”

Vera Molnar to Zsofi Valyi-Nagy (translated from Hungarian), Paris Dec 19, 2017

“Molnar used a computer program to translate a soft, elegant, hand-coloured photograph of her late mother, Erzsi, into her own visual language of black-and-white geometric forms.”

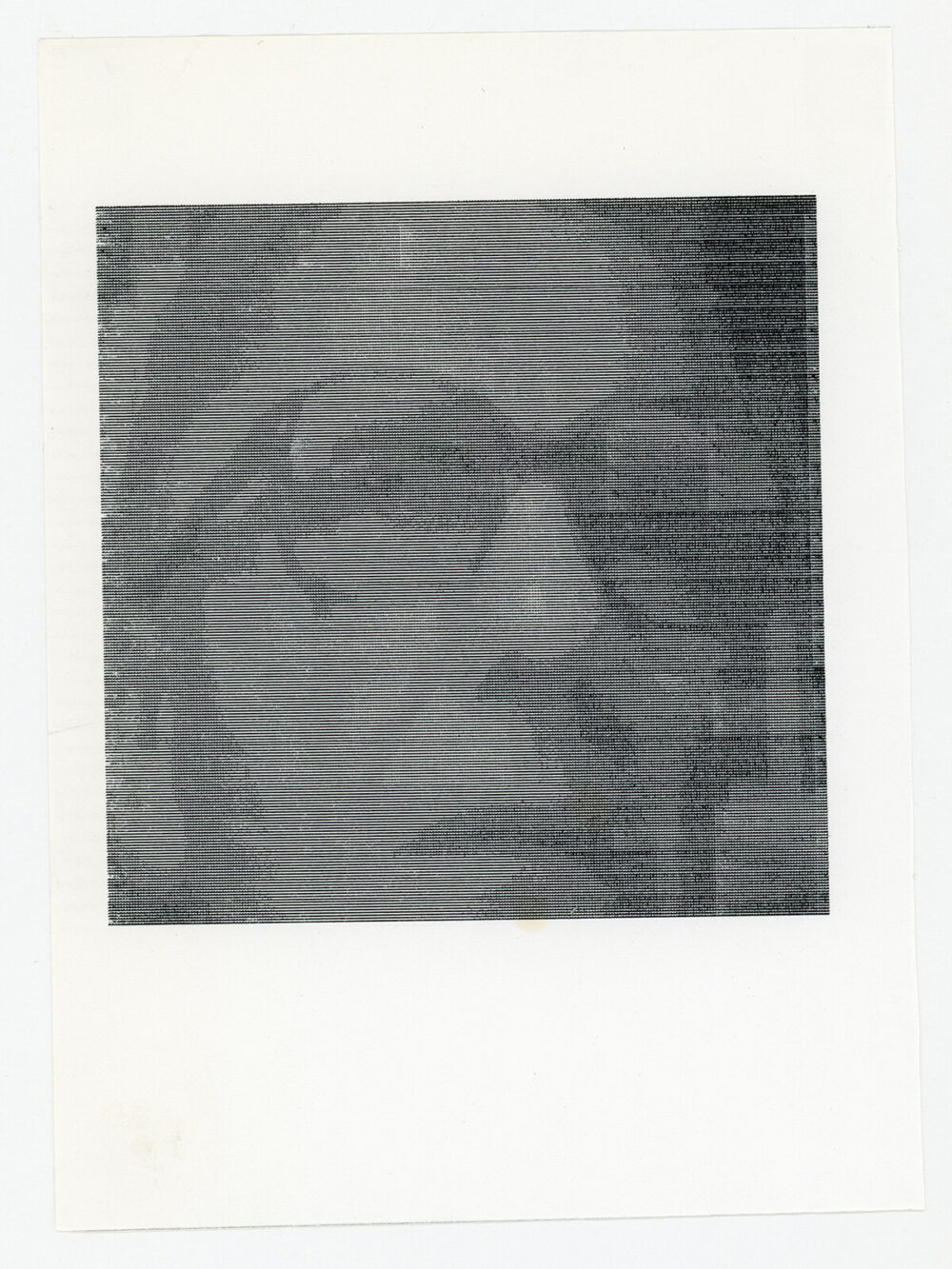

Various iterations of the computerized portrait of her mother that Molnar created based on a photograph from the 1920s.

In 1988, on the brink of major transition in Europe, Vera Molnar also shook things up in the studio. After nearly four decades of strict geometric abstraction, she made a portrait. Her first major figurative work since her twenties, Portrait de ma mère (Portrait of my mother) is still unmistakably hers, with its monochromatic minimalism and distinctive plotter-drawn lines. Molnar used a computer program to translate a soft, elegant, hand-coloured photograph of her late mother, Erzsi, into her own visual language of black-and-white geometric forms. Portrait de ma mère, alternately titled Portrait de ma mère en rectangles, atomizes the original photograph into small rectangles, the result somewhere between pointillism and ASCII art. At least eleven versions of the portrait exist, many of them bearing the grainy marks of a photocopier—within each variation there are more variations. In each portrait, Erzsi’s face seems to emerge from a hole in the page, her face serene, confident, legible as a portrait but not tremendously recognizable. We might even say it could be a portrait of anyone’s mother.

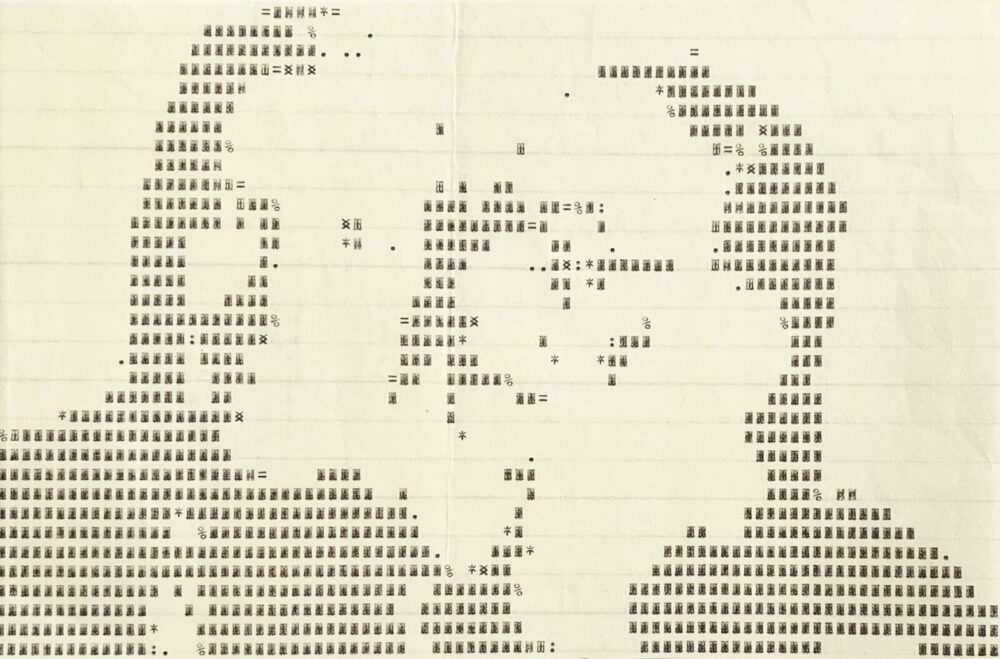

There is very little documentation of how this work was made, and Molnar’s own memory of the process is fuzzy. She recalls using a premade computer program, rather than one she wrote herself.1 Actually, this was technically not Molnar’s first return to figuration. In 1974, she and François Molnar visited Bell Laboratories in New Jersey with their friend Béla Julesz, a fellow Hungarian emigré who, like François, used computers in perceptual psychology research. They returned to Paris with a prized souvenir, a computerized ‘double self-portrait’ made from a snapshot of the couple. Like the small dots of a Seurat painting, the image is made up of small rectangles, asterisks, percentage signs, and other alphanumeric characters, drawn in black ink with a plotter. As in pointillism, the figures become more distinct when viewed from further away. We can make out François, looking straight at the camera, while Vera, recognizable by her glasses and chignon, appears to look past him. The yellowed, lined paper bears a crease, not down the middle, but exactly where their faces meet. Like Portrait de ma mère, this image was made using someone else’s program, and its style matches many computer-manipulated photographs of the era, from Harmon and Knowlton’s Computer Nude (1967) to Waldemar Cordeiro’s images of figures. Surely Molnar had the Bell portrait in mind when she returned to portraiture in the late ’80s. But the reference she chose to make was more art historical; she titled a series of seven portraits of her husband, made from digitized photographs but with a much denser matrix of characters, à la manière de Seurat (1988).

A prized souvenir: The ASCII portrait of Vera and François Molnar was drawn during the couple’s visit of the Bell Laboratories in New Jersey.

A series of seven portraits of Molnar’s husband, François, made from digitized photographs.

Molnar made Portrait de ma mère in dialogue with another series, Lettres de ma mère, a computer ‘simulation’ of Erzsi’s handwriting that is also included in the show, and which I will discuss in a later entry. The portrait graces the cover of an edition of screenprints of the letters made for the Vasarely Museum in Budapest, and it’s printed at the outset of her article “My Mother’s Letters” in Leonardo journal. By running Erzsi’s likeness through this program, Molnar’s early life collides with her life as an artist, as a pioneer of computer art.

Vera’s mother, like her beloved Mona Lisa, has an enigmatic smile, and like Leonardo’s famous portrait, Portrait de ma mère might be seen as blurring portraiture with self-portraiture. Though she could have easily included an untouched photograph of her mother alongside the Lettres, she decided to manipulate it, to abstract it almost to the point of anonymity. As with the asemic writing of the Lettres, Molnar takes something intensely personal and uses abstraction to make it more universally relatable. But this process of abstracting also becomes a sort of screen, which shields Molnar and her Mother from being seen too closely.

The plotter drawing (bottom) is shown with the related series Letters de ma mère that simulates her mother’s handwriting.

Over the past five years, I have built a relationship with Vera Molnar that is rarely possible between artist and art historian. Any historian who has written extensively about a living practitioner knows that it can be equal parts exhilarating and frustrating. Molnar and I have a beautiful intergenerational friendship, but it involves a constant re-negotiation of boundaries, a shift between calling her Vera and calling her Molnar, as I have done in this essay without even realizing it.

I still remember our first phone call, in August 2017. It was a cold call, from my computer in Chicago to her landline in Paris. I rehearsed all the formalities, all the awkward turns of phrase that would signal my respect for the 66-year age gap between us. Growing up in the United States, I spoke Hungarian only with family, using tegezés, the most familiar form of address. Even as my circle of Hungarian friends widened as I grew up, the language still feels familial to me, as if speaking magyarul means we are at least distantly related. This rings especially true with anyone belonging to the Hungarian diaspora. As a heritage speaker, the prospect of having to use formal Hungarian makes me anxious, and using it to speak to a famous artist I admired only compounded the anxiety.

“How would Madame Molnar like to be addressed?” I shouted into my laptop for the third time in a patchwork of Hungarian and French words, my voice shaking. Silence. I feared I had said something wrong. I held my breath. Then, on the other end, laughter. “Nyuszikám,” she said in her sonorous, deep voice. “My little rabbit. I left Hungary when I was twenty-three. I don’t care about that sort of thing. You can call me Vera.”

I returned a laugh, relieved. It was more than just her irreverence toward stuffy hierarchies that I was grateful for. Her invitation meant more than a simple on peut se tutoyer. The only elderly person I had ever address this way in Hungarian was my grandmother. With a simple “call me Vera,” the distance between us seemed to collapse.

To this day, I don’t think our bond would be the same if we didn’t speak in our mother tongue. And yet, even as I peruse her archives and get closer to her, whether she is Vera the artist or Vera the pseudo-grandmother, I realize that I will never know her fully. The closer you get, the more the picture dissolves into tiny geometric forms.

References:

(1) The best we can do, to understand how the image was made, is to reverse-engineer it. To do this, I borrowed the technical expertise of my friend Jonah Marrs, who helped me see the portraits through the eyes of a creative engineer. We counted and measured the characters making up each variation of the portrait. Marrs suggested re-programming the work using an ASCII image generating program in Processing, replacing the alphanumeric characters with box-drawing characters, which are semigraphics typically used to draw geometric frames and boxes.

╠ ╵ │ └ ├ ┘ ┤ ┴ ┼

▁ ▂ ▃ ▄ ▅ ▆ ▇ █ ▉ ▊ ▋

For almost a decade I’ve taught a class where we recreate artworks from the past in order to have a better understanding of the roots of computational art—each week we focus on a different practioner. Without fail I begin each semester with Vera Molnar’s work, because it offers us a chance to explore randomness and order but also, it’s a great class opener because her work is warm and ultimately about a kind of conversation with machines. Usually beginners get excited when they see the random() function; they create glitchy, frenetic and madening compositions where everything on screen rearranges itself every frame. But Vera’s work invites slowness and contemplation—it invites us to converse with randomness, to nudge a vertex over here, to delete a line over there, to push and pull at geometry until we agree or not, and begin again.

Zach Lieberman is a Brooklyn-based artist, researcher and educator. His projects have won the Golden Nica from Ars Electronica, Interactive Design of the Year from Design Museum London as well as listed in Time magazine’s Best Inventions of the Year. He creates artwork through writing software and is a co-creator of openFrameworks, an open-source C++ toolkit for creative coding and helped co-found the School for Poetic Computation, a school examining the lyrical possibilities of code.

“What fascinated Molnar about computers was more practical than speculative or futuristic. It was their capacity to compute, and to do so accurately, quickly.”

Before she had access to an electronic computer, Molnar worked with what she called the machine imaginaire, an imaginary computer or “a computer without a computer.”1 Molnar already knew what computers were, and what they could do, from books and magazines. While popular literature on computers focused on the looming question of artificial intelligence, the ‘electronic brain’ that might one day replace the human (a concern more rooted in science fiction than reality), what fascinated Molnar about computers was more practical than speculative or futuristic. It was their capacity to compute, and to do so accurately, quickly, and on a scale infinitely larger than a human could do alone. Perhaps what she found most appealing was how the computer crunched numbers and made decisions without the interference of what Molnar called “cultural ready-mades”—bias that might influence a human’s decision-making process. The idea was this: while an artist might make decisions according to principles of “good form” or “good composition” they learned in art school, the computer started with a clean slate, and could therefore make ‘objective’ decisions.

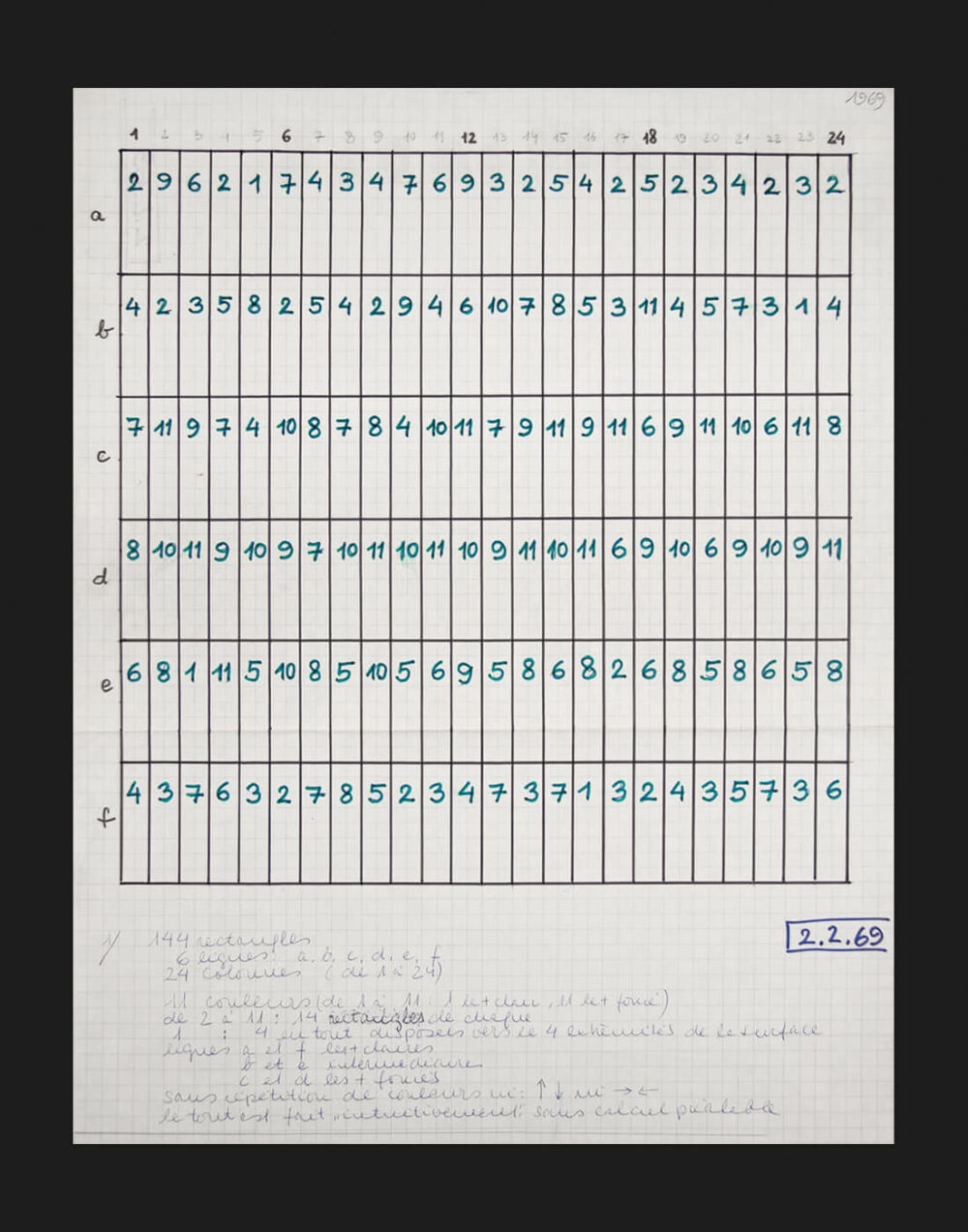

In the early 1960s, as the electronic computer remained expensive and out of reach, Molnar emulated its objectivity by hand-writing simple ‘programs’ to generate series of pictures. The machine imaginaire algorithms used basic combinatorial mathematics, the area of math concerned with problems of selection, arrangement, and operation within a finite or discrete system. Like a scientist conducting an experiment, she would alter only one variable or parameter in each iteration or variation, such as the choice of color or the angle of inclination of line segments. To make these changes, she often employed a rudimentary random-number generator: a roll of dice or the flip of a coin.

Molnar argues that her shift from machine imaginaire to machine réelle, in 1968, was not a radical break but rather a continuation of the same method with different tools. The digital computer, she wrote in Leonardo, was able to “facilitate the execution of this time-consuming procedure.”2 Using the computer was, put simply, more accurate and more efficient than executing programs by hand.

While 1968 is framed as such a pivotal moment in Molnar’s career, there are very few extant works from this period that bear visible traces of the computer. Skeptics might even say that her role as a pioneer of computer graphics has been exaggerated. Perhaps the reason Molnar’s earliest experiments are fuzzy to history is because we’re not looking for the right kind of evidence.

Let’s return to Molnar’s first encounter with the computer that I discussed in the context of her friendship with the composer Pierre Barbaud. On Barbaud’s invitation, Molnar visited the mainframe computer at Bull–General Electric in Paris. She went in wanting to experiment with random color distribution, but quickly found that they only had the hardware for monochrome graphics. So Molnar developed a program that generated a list of numbers (referred to as a listing in French), each corresponding to a color. Then, like a game of Paint By Numbers, she colored a grid of squares by hand according to these results. The image is not a plotter drawing; in its process, it is closer to the work of Jean-Claude Marquette, working across town in the other Groupe de l’art et informatique, who also used a listing to fill quadrille paper, which he then transposed to paint on canvas. Molnar, however, quickly tired of this method, and wouldn’t do it again. That was when she sought out the computer lab at Orsay, the Centre de calcul interrégional de calcul électronique (CIRCE), which had two different kinds of plotters; here, she could not only design pictures with computers but actually execute them computationally as well.3

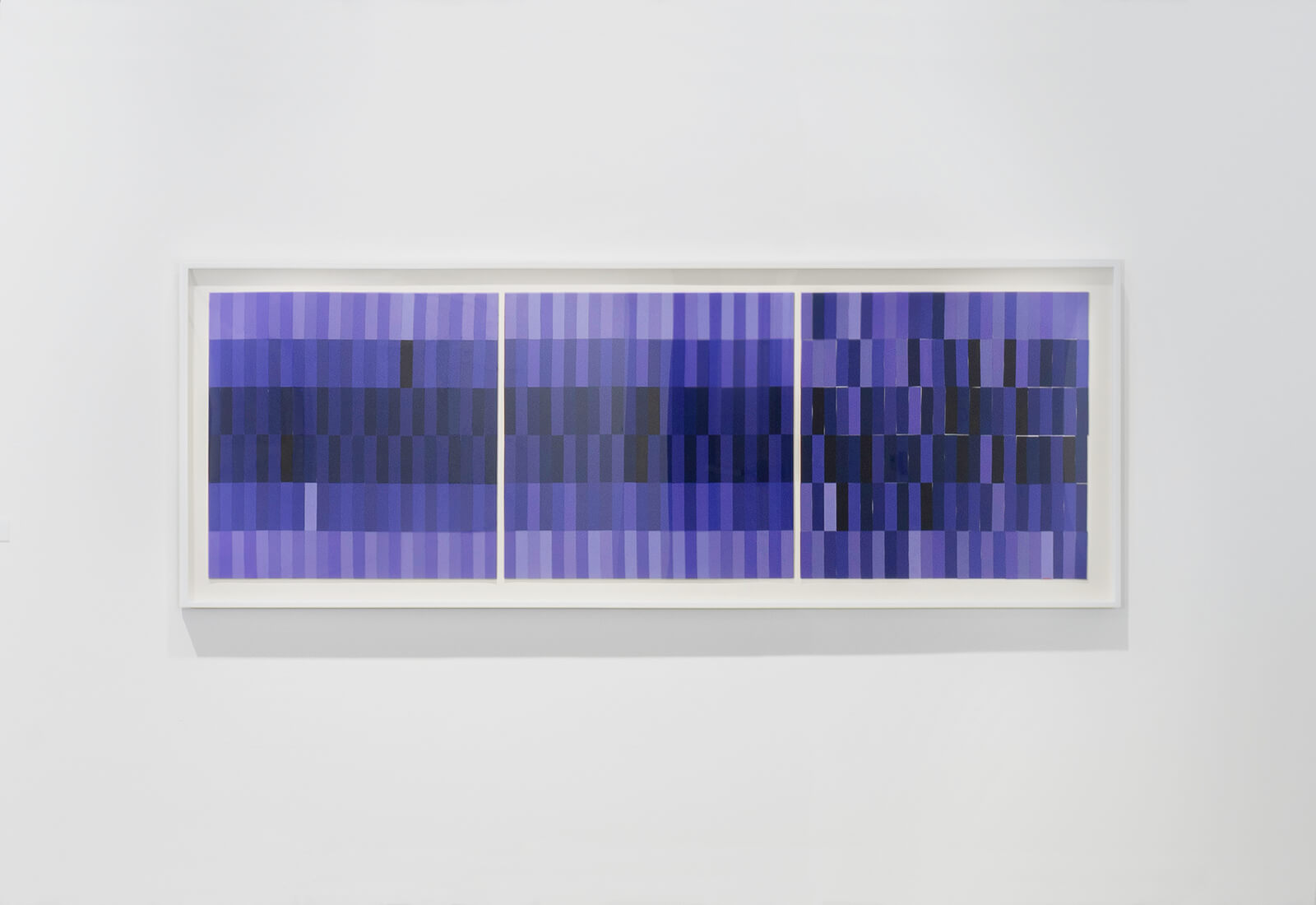

Molnar reminds us, however, that just because she started using a computer in the late 1960s doesn’t mean that she never made anything by hand again. It’s always been a back-and-forth for her—an idea that she crystalized in her recent artist’s book Main/Machine (Hand/Machine). David Familian, curator of the “Variations” exhibition, recently asked me about a triptych of collages in the show that Molnar made in 1969, 144 Rectangles. Did I know whether she used a computer here, or just a flip of a coin, to determine the placement of each purple rectangle? I shared Molnar’s anecdote about the listing—that some of her works, especially from this early period of computation, utilized the computer but were ultimately still handmade. It was a sort of “extension of the machine imaginaire,” David observed, “but instead of using a coin, she was using a computer.”

In other words, it would be reductive to divide Molnar’s work into pre- and post-computer art, with 1968 serving as a major turning point. The digital computer entered Molnar’s practice not with a bang, but gradually. We might even say that each step forward was followed by two steps back, until she figured out how the machine would best serve her interests. While Molnar has never presented herself as a ‘generative’ artist—this label is relatively recent, though not one she has explicitly rejected—the term feels especially appropriate here, for it acknowledges that an artist can work with systems and algorithms without necessarily using a particular technological tool. To focus on the generative is to focus on the artist’s process, which is what matters the most anyway.

References:

(1) Baby, Vincent. “Introduction à la « machine imaginaire » / Introduction to the ‘imaginary machine.’” In Vera Molnar: Pas froid aux yeux, edited by Vincent Baby and Francesca Franco. Paris: Bernard Chauveau Editeur, 2021.

(2) Molnar, Vera. “Toward Aesthetic Guidelines for Paintings with the Aid of a Computer.” Leonardo 8, no. 3 (1975): 185.

(3) Conversation with the author, Oct 10, 2021

Vera Molnar is probably one of the artists who fascinates me the most. I started collecting her work when I was in my early twenties, and I was particularly amazed by her exhibition “(Un)Ordnung. (Dés)Ordre” at Haus Konstruktiv in Zurich in 2015. I believe that she and a few other pioneering artists gave a very concrete answer to the recurring question—still relevant today—of what machines can do for the artist. Now, as artificial intelligence technologies spread to all sectors of society, the question is completely reversed: what can’t the machine do for the artist? By using personal memories—as in Lettres de ma mère, by imagining algorithms as a form of intimate writing, by going beyond the pure computer medium to project forms into reality, Molnar opened up many avenues, which I am continuing to explore within aurèce vettier.

aurèce vettier is a studio founded by Paul Mouginot in 2019. The collective aims to understand how relevant and meaningful interactions with machines and algorithms can be achieved, in order to push the boundaries of creative processes. With poetry as the backbone of the practice, the works and installations of aurèce vettier have been shown in numerous physical and digital spaces including Feral File, the Brownstone Foundation, Asia Now, the Cultural Foundation of Tinos, and Darmo Gallery in Paris.

“It’s a vein of media theory that sees history not as a linear, teleological progression of technologies but rather as nonlinear processes that leave behind material traces.”

Earlier this year, I moved to Berlin for eight months on a DAAD research fellowship. With Molnar based in Paris and hailing from Budapest, how did I end up in Germany on the last leg of my dissertation research trips? First, Molnar’s work has been collected and shown here more than in any other country outside of France. If you’ll forgive the cultural stereotype—Germans love squares. But the main draw of Berlin, for my research, was the Media Archaeological Fundus at Humboldt University, headed by Dr. Prof. Wolfgang Ernst. What is media archaeology?

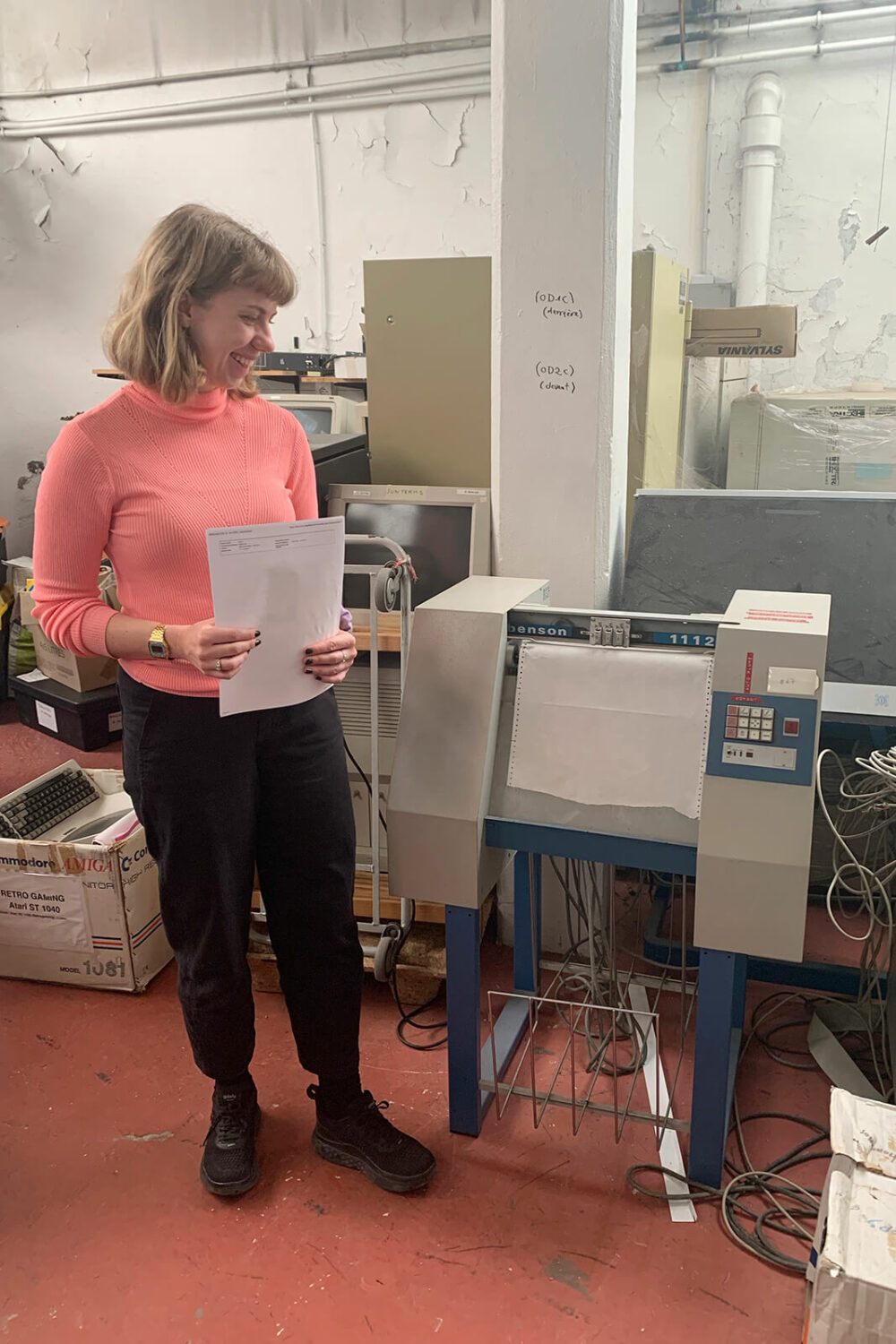

Media archaeology is a vein of media studies that sees the history of media not as a linear, teleological progression of technologies but rather as a series of nonlinear processes that leave behind material traces. The ‘Berlin school’ of media archaeology, led by Ernst, has a special interest in studying media by actually using it. They are devoted to collecting obsolete technologies and making them operational again, thereby bringing them into the present. I was especially excited to work with Dr. Stefan Höltgen, who, until recently, ran the HU’s Signal Laboratory, a space devoted to resuscitating microcomputers, mainly from the 1980s. Here, I was fortunate to work with Stefan to re-program Molnar’s work on a machine she had actually used in the late 1970s, which allowed me to peer into the material world of early computer graphics and into her creative process, which is where I believe she made her biggest impact on twentieth-century abstraction and aesthetics.

The work that we re-programmed or ‘re-enacted’ is Lettres de ma mère, a series Molnar worked on throughout the 1980s. In BASIC—the last programming language she would learn—Molnar wrote instructions to draw lines that mimicked her late mother’s distinctive, calligraphic handwriting. While they look like handwritten letters, they are entirely asemic or devoid of meaning. The work has incredible poetic potential, which Molnar, writing in Leonardo, tries to stifle by insisting that it’s purely a formal experiment, an investigation into composition. But whether she likes it or not, these images invite us to read between the lines, to wonder what the letters could have been about, to reconstruct an imaginary conversation between mother and daughter across the Iron Curtain. We could say that re-making Lettres de ma mère involves a reenactment of a reenactment: by tracing the lines of the plotter, I approximated Molnar’s marks, which in turn approximated her mother’s, preserved in the letters she sent her daughter after she left Hungary in 1947 til her mother’s death in 1971.

We focused on two versions of Lettres made in 1988 on long rolls of paper that unfurl like scrolls. Since the artist left very little documentation of her computational processes—at least not the kind of documentation that would be legible forty or fifty years later—re-programming Molnar’s work involves a fair amount of creativity and reverse engineering. No two approaches to reenactment produce the same results. In this case, the first step was incredibly analog: I had to buy a protractor and reach back into my ninth-grade geometry memory to remember how to measure angles. Stefan printed out a photograph of the first ‘letter’ and I traced the lines, counting the peaks and falls of the ‘handwriting’ and measuring the length of each mark. With this data, I was then able to start designing a computer program that could produce this kind of zigzagging line.

It was serendipitous that a collector of obsolete computers in Berlin happened to have a working Tektronix 4052, the microcomputer that Molnar would have worked on in the late 1970s at the Centre Pompidou’s computer lab, the Atelier de recherche des techniques avancées (ARTA). While this is not the machine Molnar used to make Lettres (that was an Apple II clone and later an IBM PC clone called the BFM), the point was not to show how some specific hardware determined the outcome of this artwork, but rather to explore Molnar’s general approach to programming graphics.

‘Drawing’ in BASIC is—excuse the pun—not so basic. It took me days to figure out something as deceptively simple as drawing a line. I reminded myself that, like me, Molnar was more or less an amateur when it came to computer graphics. If she could do it, so could I. It turned out that the Tektronix 4052 was better equipped for graphics than most microcomputers of its era. In fact, its built-in oscilloscope screen put its graphics capabilities front and center. While there is a functional Tektronix emulator online, being able to program the original computer—with its whirring fan and its clunky keys and its acid-green graphics that appear on screen like flashes of lightning—was an unparalleled experience that gave me a unique insight into Molnar’s process and into the early days of computer graphics more broadly.

While art history tends to focus on objects that can be put behind glass or stored in drawers, incorporating media archaeological methods allows us to emphasize the process of making, especially when now-obsolete technologies were involved. By paying attention to these technologies and the material traces they left behind—often in the form of sketchy notes or ephemeral images—my aim is to shed light on the overlooked material history of early computer graphics, while also expanding our understanding of what constitutes a work of art, or an object of study in art history.

“Art history tends to move chronologically, but for me it’s more interesting to think thematically. A theme can go away, come back, go away, come back. Why is that? Why is it that I can suddenly think of something I haven’t thought about in ten years? I think if I weren’t an artist, I would be researching how the brain works. Why is that an idea can disappear, and then suddenly come back?”

Vera Molnar to Zsofi Valyi-Nagy (translated from Hungarian), Paris Spring 2021

“Unlike the intimate scale of Molnar’s works on paper, Déscente is larger than life, twenty feet wide and sixteen high.”

In many ways, the exhibition “Variations” is a bookend to “Transformations”—both solo shows at university gallery spaces in Anglophone countries, though 46 years and over 5,000 miles apart. Both focus on her works on paper and her experiments with computers.

The centerpiece of “Variations” is an installation titled Déscente that was previously shown at the Museum for Concrete Art (MKK) in Ingolstadt, Germany, altered ever so slightly to fit the central wall at the Beall Center for Art + Technology. Molnar has been making these large-scale wall ‘drawings’ since the early 1990s. Lines are ‘drawn’ on the wall using black string, which is strung around a series of nails and pulled taut. Her first work made this way was Hommage à Dürer, based on Albrecht Dürer’s magic square. Here, she rolled dice—the original randomness generator, she calls it—to determine the location of the nails.

While Hommage à Dürer moves along the wall horizontally, Déscente, as its name implies, moves vertically, a descent from top to bottom. And unlike the intimate scale of Molnar’s works on paper, Déscente is larger than life, twenty feet wide and sixteen high.

From afar, Déscente looks like a crisp black line, but close up the string is fuzzy, imperfect, and organic, much like a hand-drawn line. In his wall text for the show, curator David Familian emphasizes this “‘hand-drawn’ quality in [Molnar’s] work, unexpected given its technological process.” I recall something David said to me on the phone when he was planning the show. He said that no matter how Molnar’s work is made, it always looks like drawing. What makes a drawing a drawing? Imperfect elements, inconsistencies, mistakes, tremors of the hand. Whether drawn with plotters, yarn, or the artist’s hand, Molnar’s lines are distinctly hers, oscillating between precision and imprecision.

Déscente cascades with a rhythmic movement. Following its path is like watching a pinball that takes a thousand mini-detours as it moves from points A to B before landing, with great satisfaction, at its destination. As I follow the string with my eyes, I feel my pen moving in my hand, tracing a line in the air, just like when I traced the marks of the plotter when I reenacted Lettres de ma mère. Sometimes it is easy to lose track of the thread, but it never gets tangled, staying taut from start to finish. At moments it seems to defy gravity, moving back up toward the summit before falling downward again. It’s a continuous line, a theme in Molnar’s work since her earliest ventures into abstraction.

David Familian is the Beall Center’s Artistic Director and Curator. An artist and educator, he received his BFA from California Institute of the Arts in 1979 and his MFA from UCLA in 1986. For the past twenty years he taught studio art and critical theory in art schools including Otis College of Art and Design, Minneapolis College of Art and Design, and U.C. Irvine. Familian has curated and organized the majority of exhibitions at the Beall, including “Drawn from a score” in 2017 and now “Variations.”

When I began to decide on the order of the works, I was oblivious that her works came out of the plotter in an order defined by code. Some of the works are very logical, like 36 squares, the one that starts with pure squares, then imperfect squares, and then it adds another level, another square on top of the squares, and then it distorts them and then it keeps doubling until it’s all dense. At the end, it’s totally distorted from the beginning, but you don’t notice it’s doing that until about two or three in.

I didn’t know she would disrupt the ordering process of outputting by removing image(s) from a sequence. Whether the reason is she didn’t like the image or she needed to expand the disorder embedded in the code is not important. It is her constant goal to balance the disorder and the order, and by imposing her combination of intuition and aesthetic choice on how a particular series should proceed and not relying on just the code, is one of many factors that add to the expressive power of her work.

The one series that I am really sorry I couldn’t get the complete version of was Désambulation entre ordre et chaos. If I ever do this show again, it would be my dream to have the full series. There’s a process behind it, but you can’t decipher it. So she plays with that. Sometimes you can decipher it, sometimes you can’t. Sometimes it seems like she’s messing with you [laughs]. I asked you once whether Molnar has a sense of humour like François Morellet, and you said ‘yes, absolutely.’ Then when I met her, she just had this smile! It was, like, wily. It gave me chills, that smile.

This fall, I am co-curating an exhibition called “Computational Poetics” with Hannah B. Higgins—it deals with text generated by a variety of computational processes. I am also working on an exhibition on complex systems, which are orderly, but not predictable. That will be part of the Getty Pacific Standard Time 2024 (PST) program.

Unable to obtain the score for the nail-and-thread installation commissioned for Molnar’s 2014 retrospective at the Museum für Konkrete Kunst (MKK) in Ingoldstadt, Germany, David Familian created his own based on the documentation.

Condensed and edited version of a conversation that took place on Aug 2, 2022

Zsofi Valyi-Nagy is a PhD candidate in art history at the University of Chicago, where she is writing her dissertation on Vera Molnar and the intersection between abstract art and early computer graphics in Cold War Europe. She is currently based in Berlin as a DAAD fellow at the Media Archaeological Fundus/Signallabor at Humboldt University, and is also a predoctoral fellow at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. Her texts have appeared in Art Journal and Right Click Save; Zsofi is also a practicing artist.