Chloe Stead delves into DISNOVATION.ORG’s “Post Growth” work, finding kinship futures after fossil fuels and zombie capitalism.

DISNOVATION.ORG

“Post Growth”

03.09.2020—07.02.2021

iMAL Art Center for

Digital Cultures & Technology

Brussels (BE)

© 2020-21 HOLO

“Anyone who believes that exponential growth can go on forever in a finite world is either a madman or an economist”—Kenneth Boulding, quoted in Prosperity without Growth: Foundations for the Economy of Tomorrow1

There are few childhood memories that I cherish more than the family summer holidays we spent in Aldeburgh, a small, picturesque coastal town in the Southeast of England. Aside from the pebble beaches and the pastel-coloured houses, what I remember most clearly is the patch of wall in my great aunt’s house that measured our cousins’ heights by age, which, each summer, my brother and I would add our own shaky pencil lines to before standing back to marvel at how much we’d grown.

As children, our developing bodies offer the tantalising prospect of independence, of becoming the “big boys and girls,” we so desperately wish to be. When we reach adulthood, we continue to quantify our lives through this prism, but instead of focusing on our own biology, we project outwards, measuring success through the growth of our families, our bank accounts, our businesses, and our homes. On a global scale, the prosperity of whole countries is measured by the increase of their GDP. But as the world’s economies grow, so does the gap between rich and poor. In the first three-and-a-half months of 2020, Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos earned more than the GDP of Honduras,2 making his net worth more than GDP of Iceland, Afghanistan and Costa Rica combined.3

It’s clear by now that this “fetishization and externalisation of growth,”4 to quote the author Valerie Olson, has also had a catastrophic effect on our environment. It’s equally clear that a massive paradigm shift will is going to be needed to combat the deep-seated belief—which has been entrenched by decades of post-World War II economic policies—that growth is “the equivalence of life,” and “not to grow is equivalence of death.”5 This is where artists of all varieties—filmmakers, sculptors, writers, photographers, chefs—can help. Facts have limited sway; it’s only through “telling stories in new ways,” according to academic Geoffrey Bowker, that we can “induce people to see the world differently.”6

“It’s equally clear that a massive paradigm shift will be needed to combat the deep-seated belief—which has been entrenched by decades of post-World War II economic policies—that growth is ‘the equivalence of life,’ and ‘not to grow is equivalence of death.’”

Both Olson and Bower are part of a new series of videos by the “artist-led action-research” collective DISNOVATION.ORG (in collaboration with Clemence Seurat), which are currently on display in their solo exhibition, “Post Growth,“ at iMAL in Brussels. Collected together under the title Post Growth Toolkits these short interviews act as the conceptual framework for a group of artworks by the French collective that question our society’s obsession with fossil fuel-powered growth and offer possibilities for change. Over the next few months, this dossier, entitled Life … After the Crash, will tease out some of Post Growth’s central concerns, mixing relevant external videos, links, and quotes with original mini essays and Q&As pertinent to the exhibition. Topics will include, growth and kinship, growth and indigenous knowledge, growth and energy, as well as growth and happiness. An art critic by trade, I am by no means an expert on these issues, but my hope is that we can all learn about them together. After all, as the specialists themselves would admit, for these radical ideas to be of any use, they need to break out of academia and take root in the minds of ordinary people.

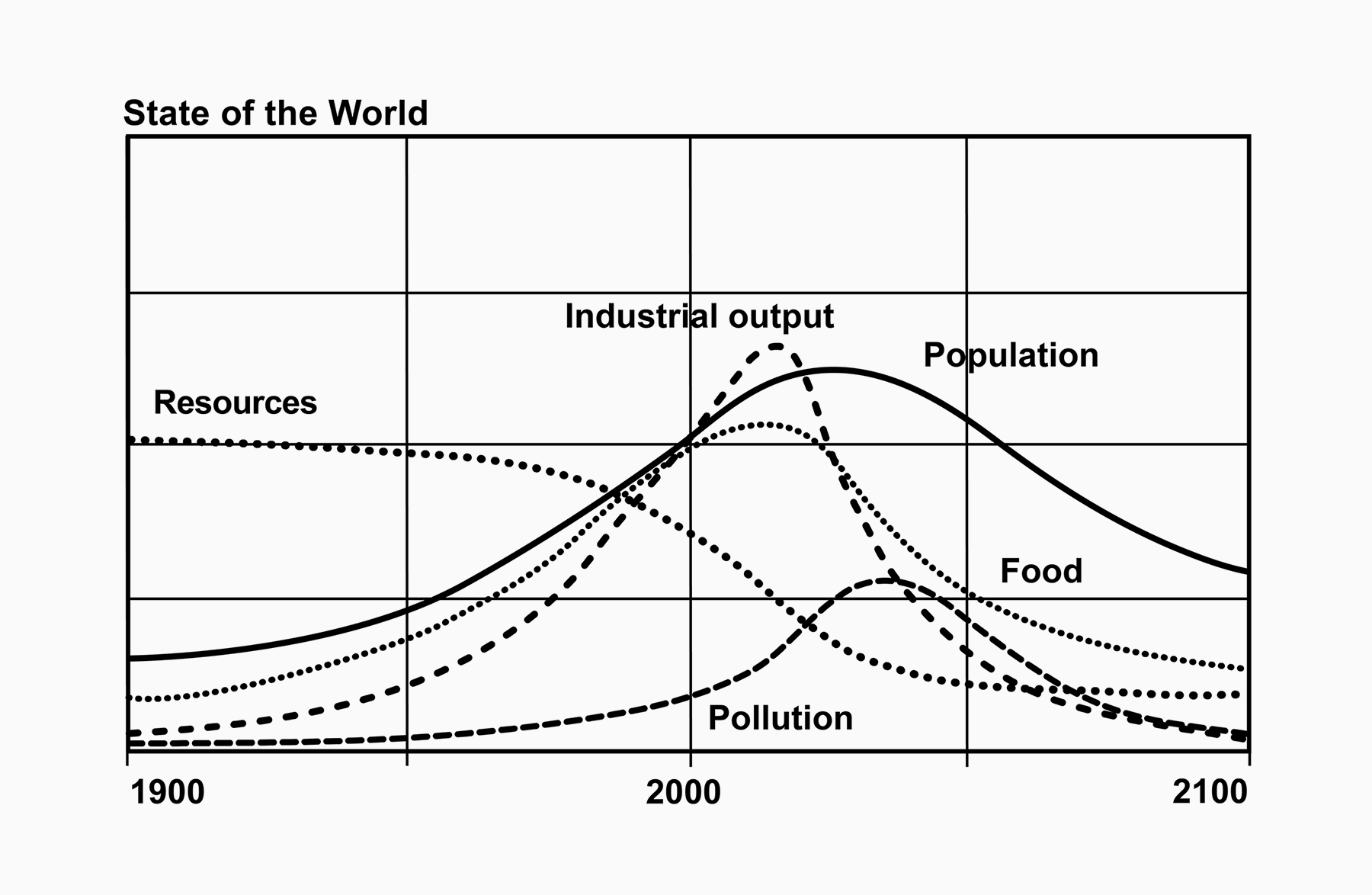

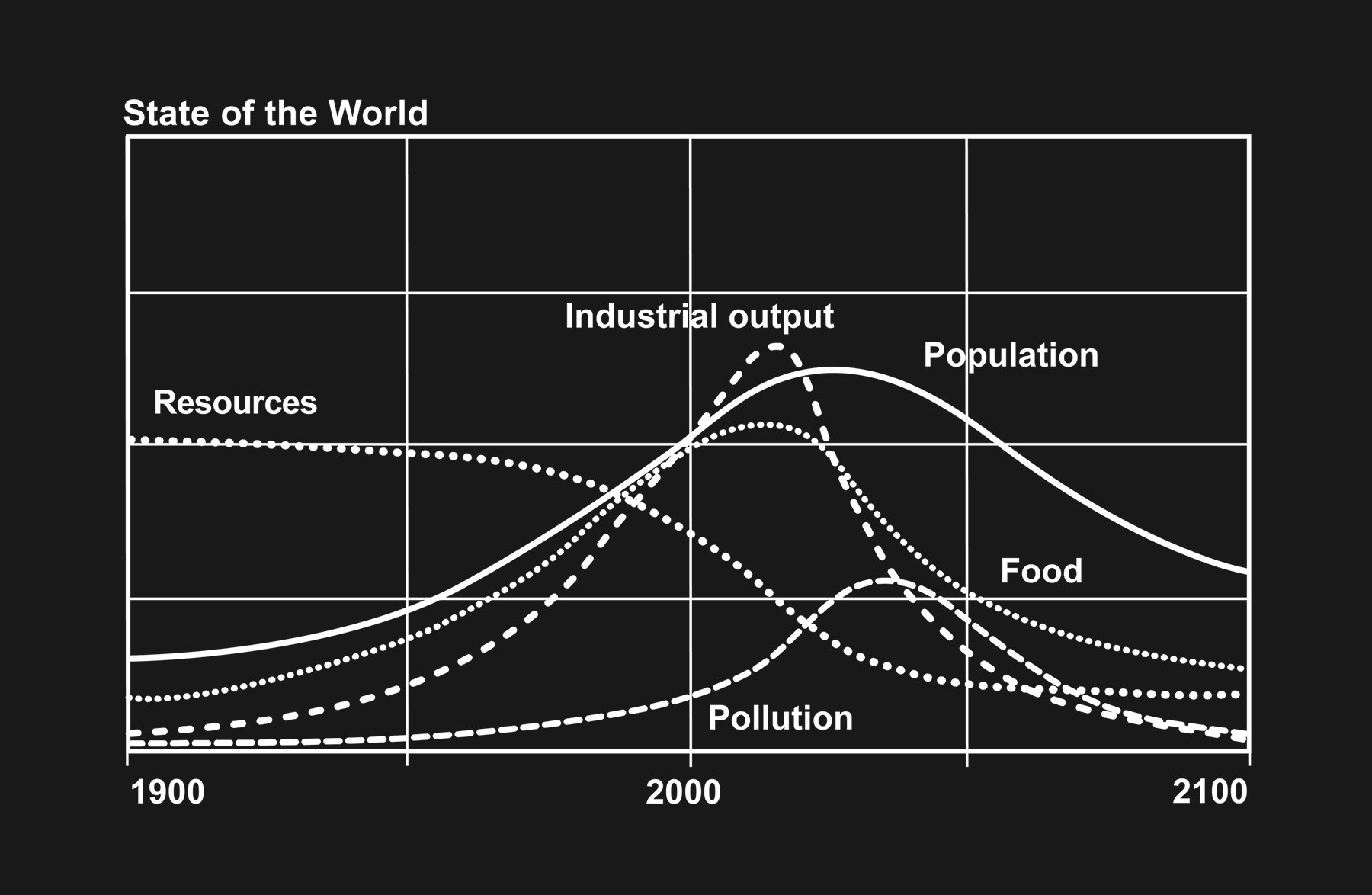

The Limits to Growth is a 1972 report on exponential economic and population growth in a finite world. Commissioned by international think tank the Club of Rome, a team of MIT researchers led by Donella and Dennis Meadows built a computer model called World3 to simulate the interactions between resource consumption, industrial output, population size, food production, and Earth’s ecosystems. After modelling data from 1900-70, the team developed a range of possible scenarios through 2100. On a “business as usual” trajectory (World Model Standard Run), the model predicted “overshoot and collapse”—in the economy, environment, and population—before 2070. Often criticized as doomsday fantasy, a 2014 University of Melbourne research paper found that the report’s forecasts are accurate, 40 years on.

“Nowadays citizens are not transforming the world around them through the use of their bodies. The primary way we transform the environment and the world around us in the twenty-first century is through prostheses, machines, automation, and computers.”

DISNOVATION.ORG is a working group based in Paris, initiated by Nicolas Maigret and Maria Roszkowska. At the crossroads between contemporary art, research and hacking, the collective develops situations of disturbance, speculation, and debate, challenging the dominant ideology of technological innovation and stimulating the emergence of alternative narratives. Their current exhibition, realized together with Baruch Gottlieb, Clémence Seurat, Julien Maudet, and Pauline Briand at Brussel’s iMAL Art Center for Digital Cultures and Technology, critically examines growth and progress through a series of artworks and filmed interviews with experts in the field.

Q: Can you give an example?

A: One example is a series of ‘energy slave’ tokens that are included in the show. The work is based on the concept of the energy slave, which was proposed by the American futurist Buckminster Fuller in the 1940s as a notion used to express the energy required to power a modern lifestyle. The concept refers to the technological or mechanical energy equivalent to the physical working capacity of a human adult. In 2020 we have an average of 400-500 energy slaves per living European, which means the lifestyle that we have is the result of about 400-500 times the energy that a single human body can produce. To grasp those orders of magnitude, we started to build bitumen bricks or units of measure that are basically embodying the energy equivalent in fossil fuel of various durations of human labour. We thought that this direction of work was quite eloquent as fossil fuel is the core driver of the global techno-infrastructure. Nowadays citizens are not transforming the world around them through the use of their own bodies. The primary way we transform the environment and the world around us in the twenty-first century is through prostheses, machines, automation, and computers. We recognized that in order to better understand our condition, and what a desirable outcome could look like, it was essential to understand this very material-informed model of how we interact with the world today.

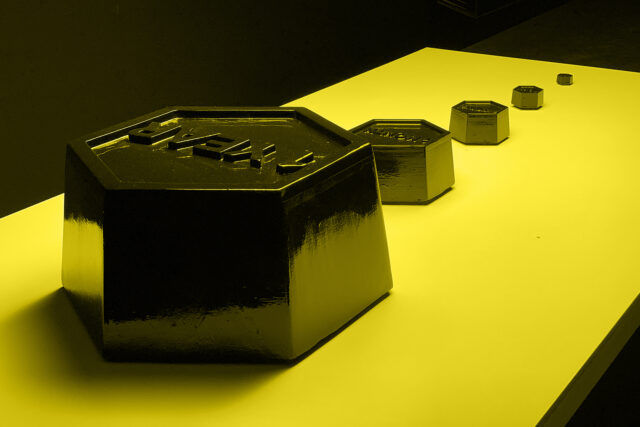

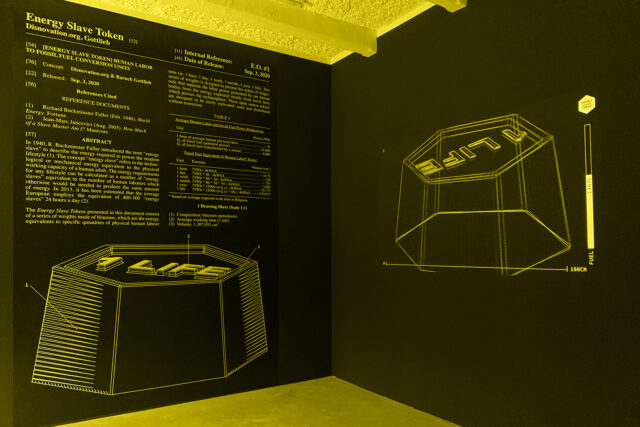

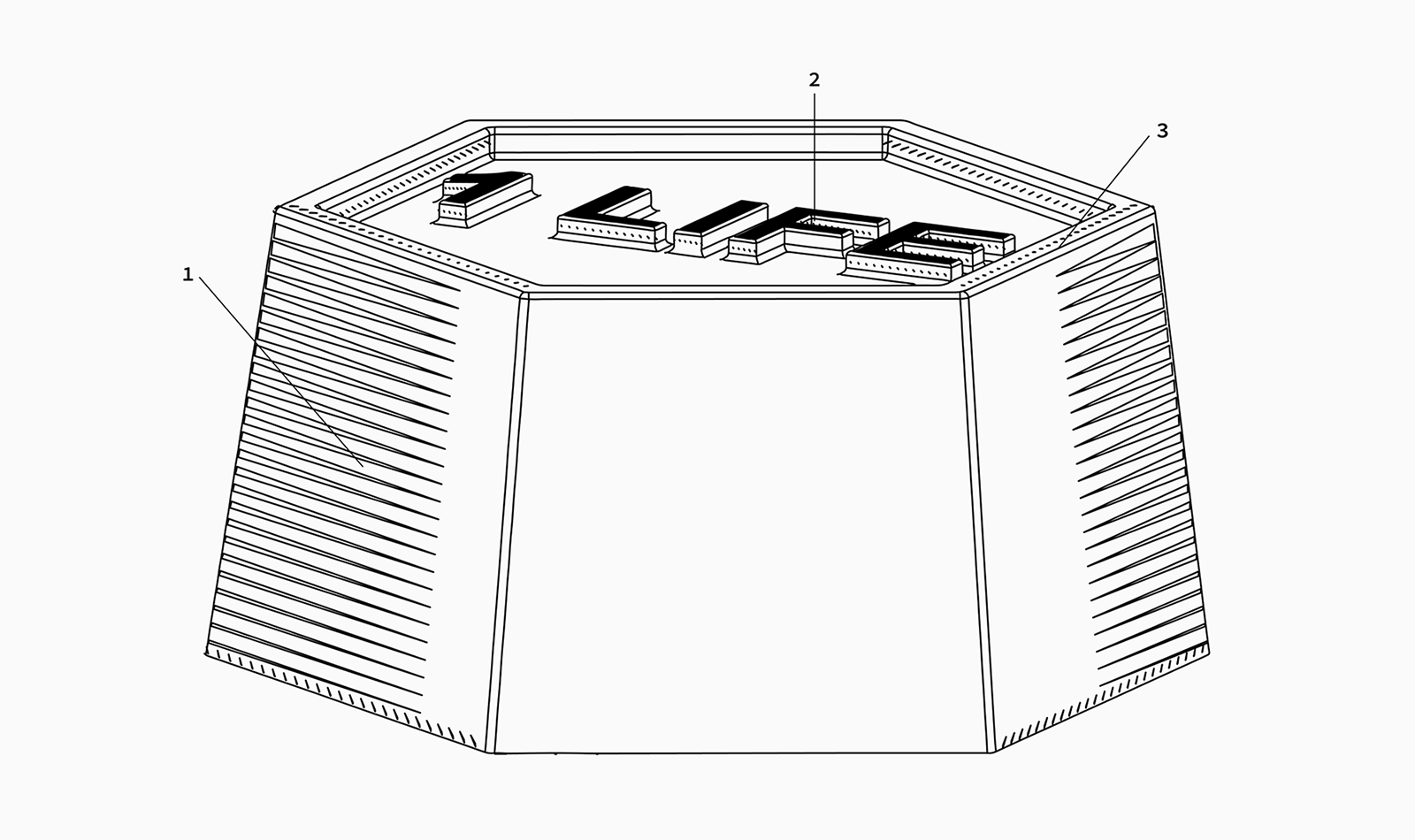

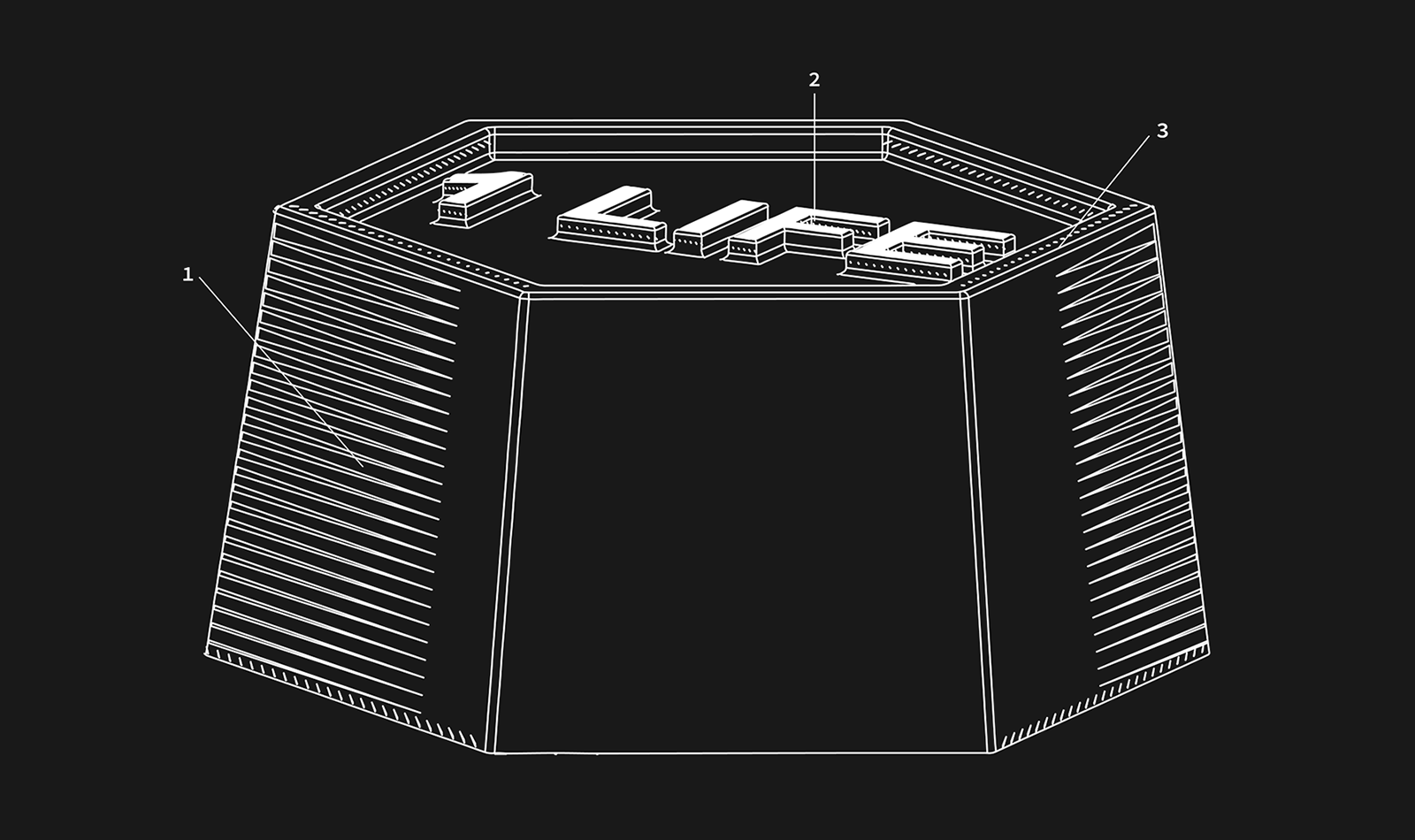

Energy Slave Token (2020)

DISNOVATION.ORG & Baruch Gottlieb

“The piece consists of a series of weights made of bitumen, which are the energy equivalents to specific quantities of physical human labour time.”

In 1940, R. Buckminster Fuller introduced the term “energy slave” to describe the energy required to power the modern lifestyle.6 The concept refers to the technological or mechanical energy equivalent to the physical working capacity of a human adult. The energy requirements for any lifestyle can be calculated as a number of energy slaves equivalent to the number of human labourers which otherwise would be needed to produce the same amount of energy. In 2013, it was estimated that the average European employs the equivalent of 400-500 energy slaves 24 hours a day.7

The Energy Slave Token consists of a series of weights made of bitumen, which are the energy equivalents to specific quantities of physical human labour time (ie. 1 hour, 1 day, 1 week, 1 month, 1 year, 1 life). This series of weights is designed to present the orders of magnitude that separate the labour-power generated by our human bodies from the energy exploited mostly from fossil fuels which power the technosphere. These open source tokens are designed to be easily replicated, used and distributed without restriction.

Average Human Labour and Fossil Fuel Power Productivity:

1 hour of average human physical labour: 75Wh

1 L of fossil fuel (potential power): 10,000Wh

1 L of fossil fuel (transformed by a motor): 4,000Wh

Fossil Fuel Equivalent of Human Labour Power:

1 hour: 75Wh / 4k Wh/L = 18.75 cm3

1 day: 75Wh * 8h / 4k Wh/L = 150 cm3

1 week: 75Wh * 8h * 5d / 4k Wh/L = 750 cm3

1 month: 75Wh * 8h * 5d * 4 w / 4k Wh/L = 3,000 cm3

1 year: 75Wh * 1590h (avg y) / 4k Wh/L = 29,775 cm3

1 life: 75Wh * 1590h (avg y) * 45y / 4k Wh/L = 1,399,875 cm3

(1) Composition: bitumen (petroleum)

(2) Average working time (1 life)

(3) Volume: 1,387,935 cm3

Energy Slave Token (Human Labor To Fossil Fuel Conversion Units), 2020, DISNOVATION.ORG & Baruch Gottlieb, installation, series of 5 standard weights, poster, 3D video

Images and text courtesy of DISNOVATION.ORG and iMAL

“As it’s understood biologically, there’s a sort of naturalization or an objectification of the idea of growth as being the central and core principle of understanding life.”

Valerie Olson researches contemporary sociocultural processes that remake what counts as environments. Her current projects focus on how social groups use the system concept to perceive, organize, and control spatial relations, particularly on large scales. This focus allows her to follow the ways people relate to sites, things, and processes they do not experience directly and which are categorized as outlying or beyond human. She serves on UCI interdisciplinary research teams and campus initiatives such as Water UCI, the Salton Sea Initiative, the UCI OCEANS Initiative, and the UCI Community Resilience program.

A transcript of the video can be found here. For more “Post Growth” interview segments with Valerie Olson visit postgrowth.art.

“What a difference 20 years and a global pandemic makes. Where once only dictators and movie villains celebrated genocide, now gap year hippies and grumpy uncles are getting in on the act too.”

A few weeks into the first Europe-wide lockdown, I started seeing an unfamiliar meme spread across my social media channels. “We are the virus,” it read. “Coronavirus is the cure.” It wasn’t until months later during a boredom-induced re-watch of The Matrix that I realized I’d heard this sentiment before. “Human beings are a disease, a cancer of this planet,” says Agent Smith to Morpheus, his voice dripping with disdain. “You’re a plague and we are the cure.”

What a difference 20 years and a global pandemic makes. Where once only dictators and movie villains celebrated genocide, now gap year hippies and grumpy uncles are also getting in on the act. Of course, misanthropy is nothing new but as the news on the environment has become ever bleaker, this particular brand of cynicism has taken root in a way that feels fresh and scary. Speaking about the “we are the virus” trend recently, author Naomi Klein warned that it revealed authoritarian tendencies. “This is a time to be really vigilant about any idea that this pandemic is weeding out people who needed to be weeded out,” she told Teen Vogue. “These are fascist logistics.”8

But you don’t have to believe that COVID-19 is some kind of “divine purging” to show signs of ecofascism, especially when, as Klein points out, even seemingly reasonable discussions about overpopulation unfairly target developing nations. “If you look at where there continues to be the highest levels of population growth, it’s the poorest parts of the world with the lowest carbon footprints,” says Klein. “But when [that conversation] immediately moves the discussion to overpopulation, we’re changing the subject from unsustainable overconsumption by the rich to the procreation habits of the poor, and that’s a very political decision.”9

“In her 2019 article ‘Don’t Blame the Babies,’ journalist Liza Featherstone similarly argues that it is capitalism, not population growth, which is having the most damaging impact on our environment.”

In her 2019 article “Don’t Blame the Babies,” journalist Liza Featherstone similarly argues that it is capitalism, not population growth, which is having the most damaging impact on our environment. “A Zambian has nowhere near the environmental impact of an American; even though her nation has a much higher birth rate, her society isn’t nearly as carbon-intensive,” she writes. “The problem, then, isn’t kids. It’s the carbon dependence of our society, which is set up to ensure that we drive, fly, heat, cool, shop, and eat in all the most polluting ways possible.”10

For both Featherstone and Klein, the discussion around childbearing is nothing but a neoliberal conceit, designed to encourage individuals to take responsibility for climate change while leaving the biggest polluters untouched. Instead of concentrating on how many people are on the planet, they argue, we should think about how we divide our available resources across the global population. Ultimately, it comes to a choice between empathy and misanthropy, and while it might be an easy decision for many, it’s important to note it’s only the first step towards the radical restructuring of society needed for this choice to have an impact. As Morpheus tells Neo, “I can only show you the door. You’re the one that has to walk through it.”

“The polar ice caps are melting. Is it OK to have a child? Australia is on fire. Is it OK to have a child? My house is flooded, my crops have failed, my community is fleeing. Is it OK to have a child? It is, in a sense, an impossible question.… Having a child is at once the most intimate, irrational thing a person can do, prompted by desires so deep we hardly know where to look for their wellsprings, and an unavoidably political act that increasingly requires one to confront not only the complex biopolitics of pregnancy and birth, but also the intersecting legacies of colonialism, racism and patriarchy, all while trying to wrap one’s head around the relationship between the impossible extremes of the personal and the global.”

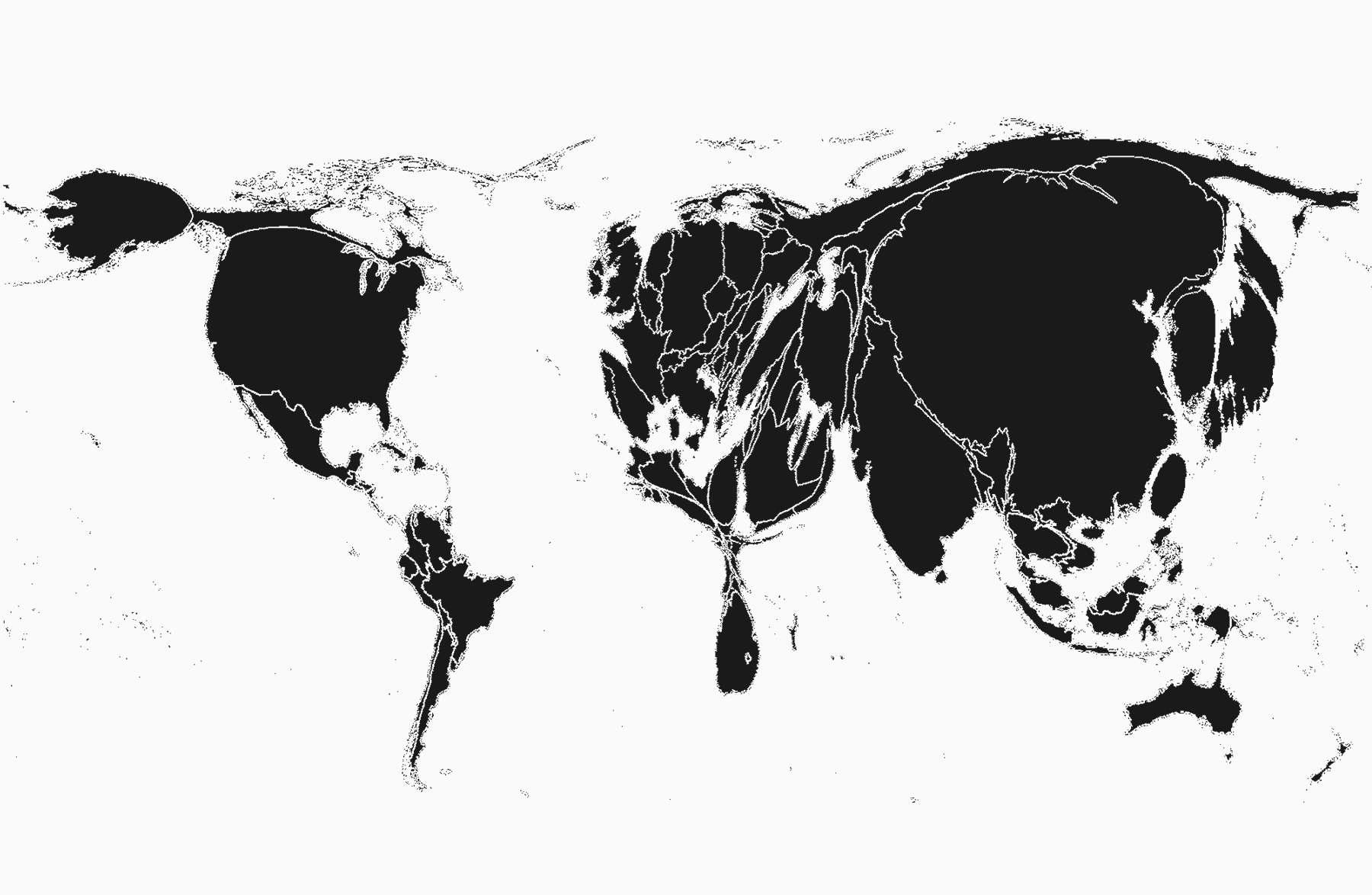

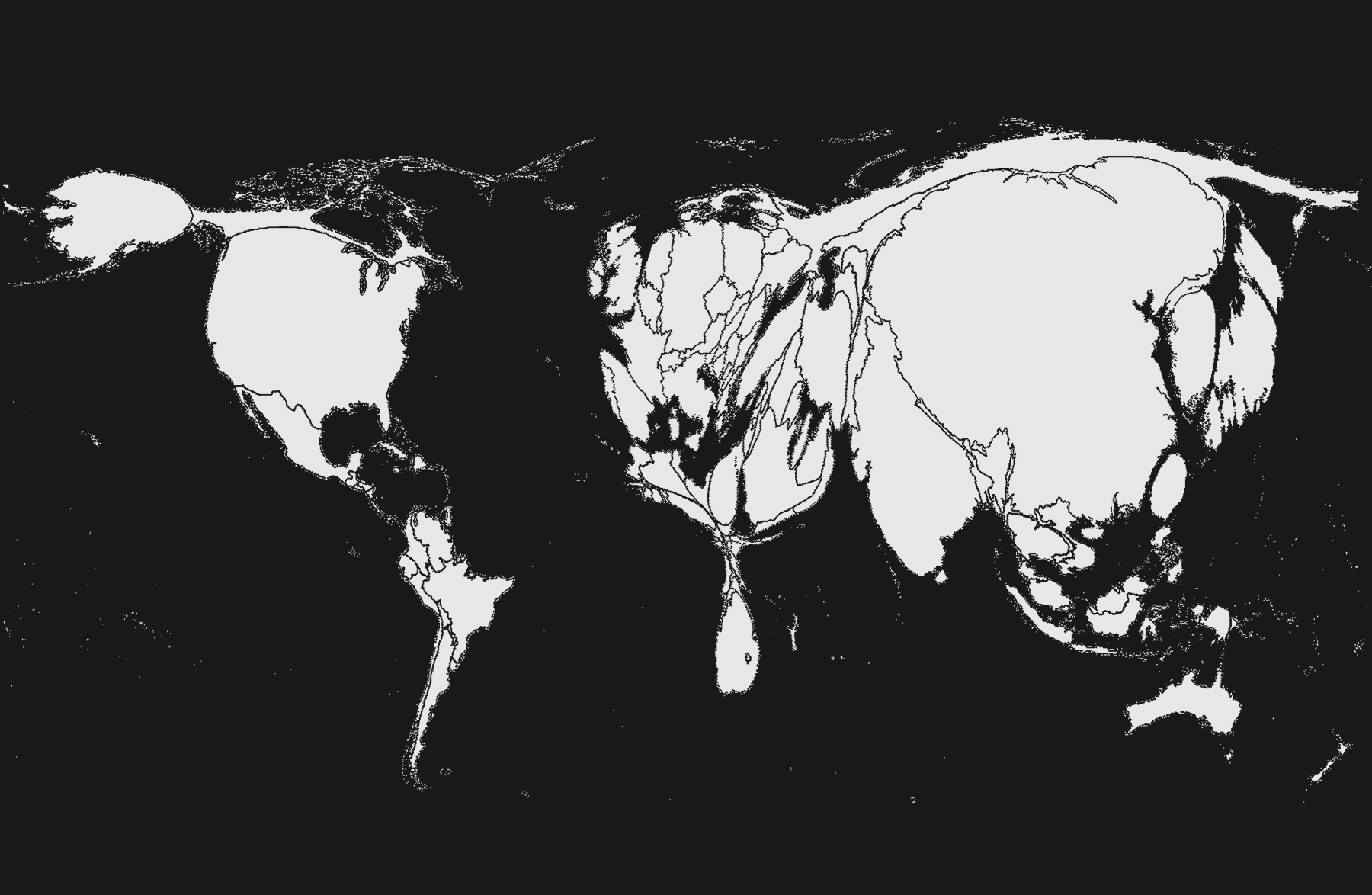

Using data by Emission Database for Global Atmospheric Research (EDGAR), this visualisation created by Worldmapper’s Benjamin Henning redraws the world according to proportion of total Carbon Dioxide (CO₂) emissions in 2015. The warped geography is telling: whereas main polluters like the U.S., home to then 320.7 million people, emitted 5,172,338 kton/Gg CO₂, the entire continent of Africa released one-fifth of that (1,236,083 kton/Gg CO₂) while harbouring three times as many people (995.46 million). As journalist Liza Featherstone argues in her 2019 article “Don’t Blame the Babies,” it is capitalism, not population growth, that is having the most damaging impact on our environment (see dossier entry 008).

“I see the art space as having a unique role to play in society today, particularly in providing a sort of safe space for the cultivation of new social and cultural practices which are needed to confront the challenges of our age.”

Baruch Gottlieb is a Canada-born media artist, researcher, and curator. He currently teaches Philosophy of Digital Art at the Berlin University of the Arts and Data Epistemology at the Technical University of Brandenburg. Gottlieb has been working closely with DISNOVATION.ORG since he collaborated on the project Online Culture Wars (2018-19). He is also a member of the Telekommunisten and Arts & Economic Group artist collectives. His books include A Political Economy of the Smallest Things (ATROPOS 2016) and Digital Materialism (Emerald 2018).

“I see the pretext of our exhibitions and other activities as centrifuges of scientific knowledge, allowing us to assemble otherwise unlikely constellations of specialists around urgent concerns. So far, this strategy seems to be working.”

Solar Share – The Story (2020)

DISNOVATION.ORG & Baruch Gottlieb

“The artistic research project Solar Share envisions the radical consequences of an economic model reconnected to the elementary sources of energy coming from the Sun, the Earth and the cosmos.”

High on fossil fuels, modernity managed to normalize the ideology according to which humankind could detach itself from the constraints and material limitations of planetary life. These constraints become harder to ignore, as the planet’s holding capacity begins to falter, and its resources run dry. How are we to reconnect with the physical, material and living reality of the world on which we depend entirely? Even today, the prevailing economic models still seem to ignore the extent to which necessary circulation of matter and energy depends on crucial physical processes for the regeneration of the biosphere or for human societies.

The artistic research project Solar Share envisions the radical consequences of an economic model reconnected to the elementary sources of energy coming from the Sun, the Earth and the cosmos. It aims to revise the prevailing narratives with an acknowledgement of the material conditions required for the persistence of our form of life in the biosphere. It proposes futuristic visions of new relationalities between humans, life and the Earth system. The computational and diagrammatic models that have emerged from this artistic research aim to engage a broad public with vital information from science. By externalizing, in artistic and aesthetic forms, the energy systems that govern the planet’s metabolism, these models are intended to supplement critical discussion of our prospects on this planet, both in specialized spheres and in the general public, with an emphasis on the unquantifiable and missing data which lurks behind and threatens to undermine scientific, political and economic confidence.

Images and text courtesy of DISNOVATION.ORG and iMAL

“In the rough and rocky future that has already begun, what kind of people are we going to be? Will we share what’s left and try to look after one another? Or are we instead going to attempt to hoard what’s left, look after ‘our own’ and lock everyone else out? In this time of rising seas and rising fascism, these are the stark choices before us. There are options besides full-blown climate barbarism, but given how far down the road we are, there is no point pretending that they are easy. It’s going to take a lot more than a carbon tax or carbon-trade. It’s going to take an all out war on pollution and poverty and racism and colonialism and despair all at once.”

“There’s no solution that’s going to come from the central government in any of this. It’s going to be us, as a species, rethinking who we are, reworking who we are, replanning who we are and then rippling that out across the whole sets of relationships that we have.”

Geoffrey C. Bowker is Professor at the School of Information and Computer Science, University of California at Irvine, where he directs a laboratory for Values in the Design of Information Systems and Technology. Bowker’s books include Sorting Things Out: Classification and Its Consequences (1999, authored together with Susan Leigh Star) and Memory Practices in the Sciences (2005), both published by the MIT Press.

A transcript of the video can be found here. For more “Post Growth” interview segments with Geoffrey C. Bowker visit postgrowth.art.

“Oil, gas, and coal have become the villains on a warming planet, but who could be against energy?”—Cara New Daggett, The Birth of Energy: Fossil Fuels, Thermodynamics, and the Politics of Work

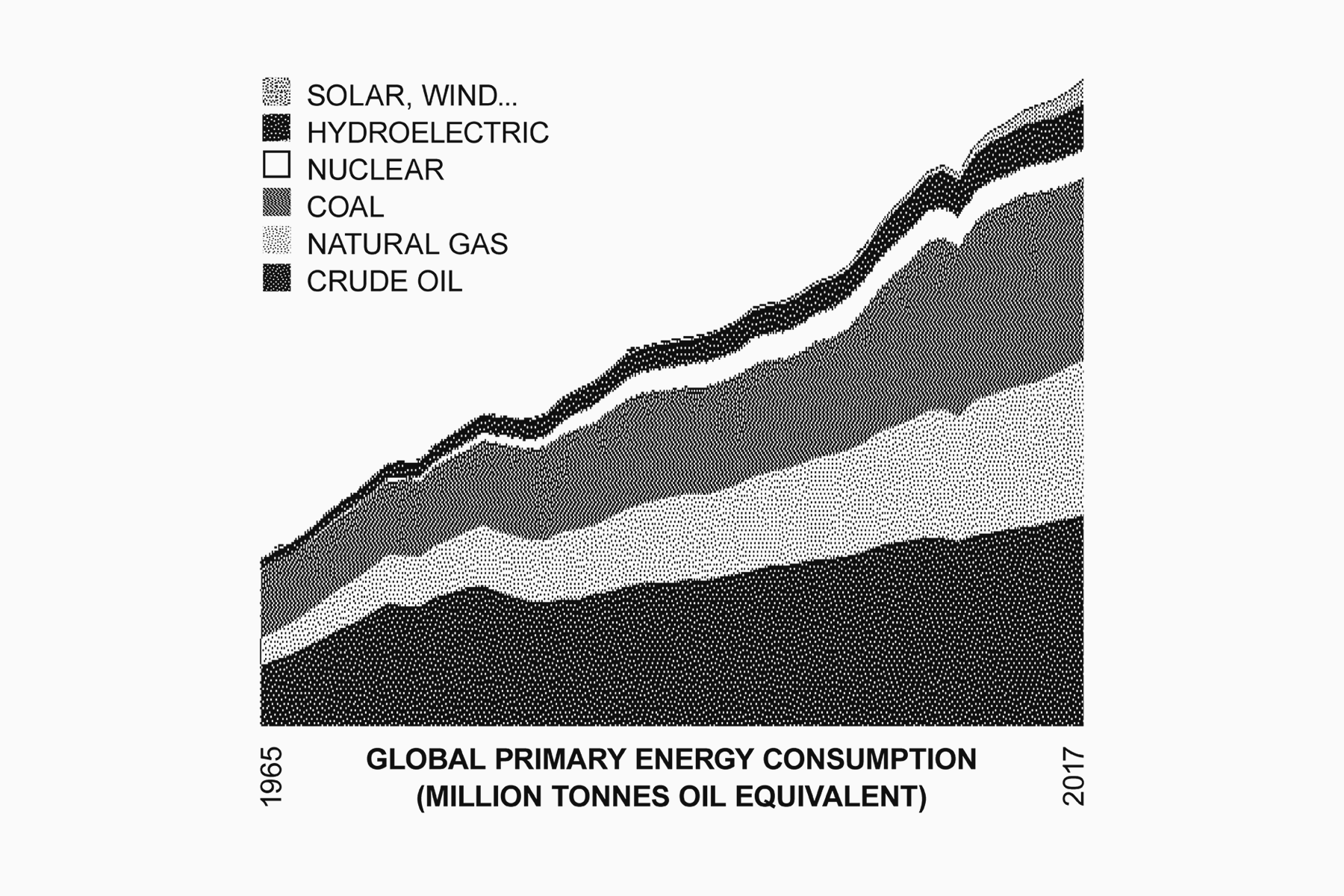

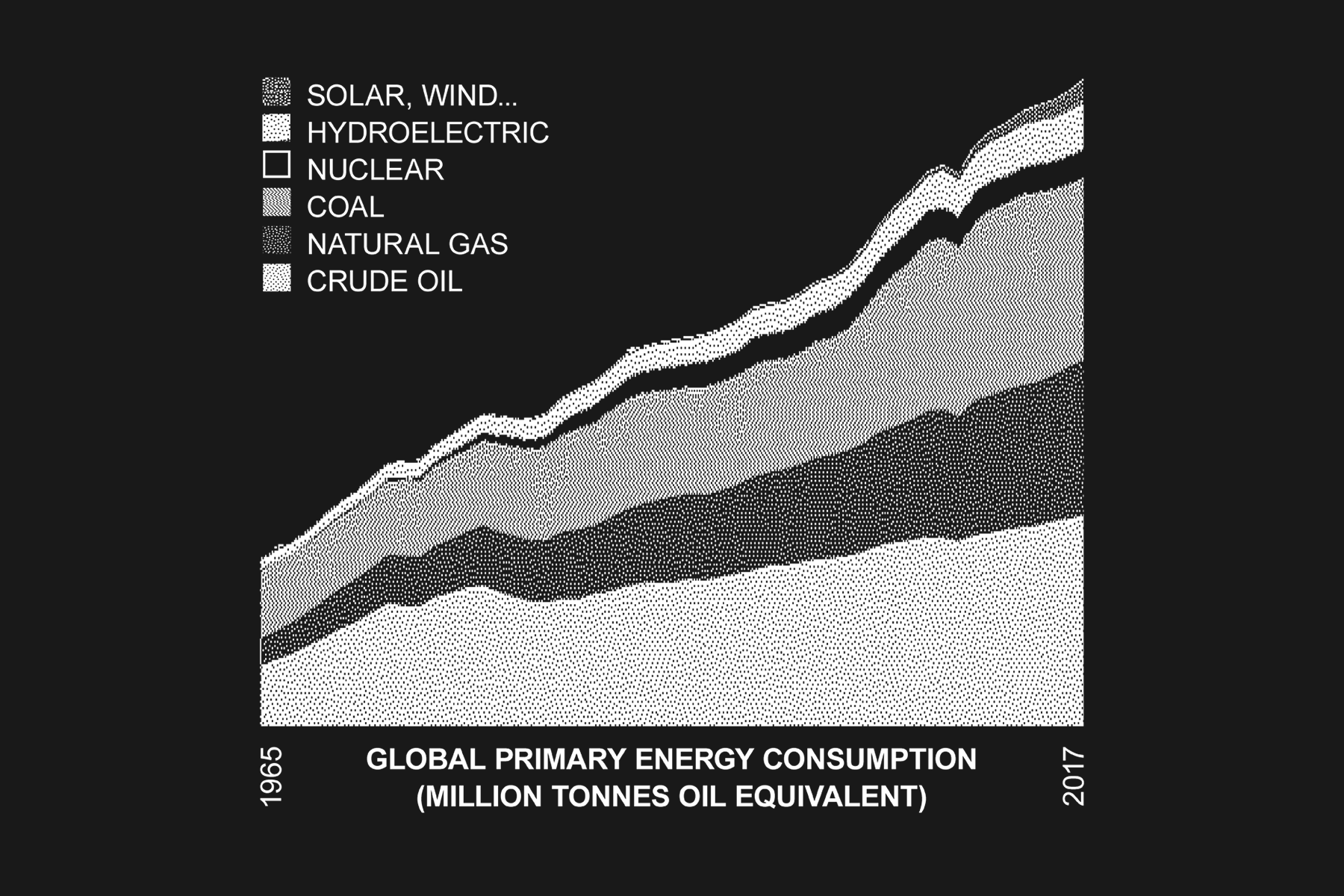

With the exception of climate change deniers, it’s clear to everyone by now that our reliance on fossil fuels is destroying the earth and threatening our continued existence. What’s talked about much less, however, is that replacing oil, gas, and coal with alternative energy sources is not, on its own, enough to avert climate disaster. As the author and climate activist Ted Trainer puts it: “It would be difficult to find a more taken for granted, unquestioned assumption than that it will be possible to substitute renewable energy sources for fossil fuels, while consumer-capitalist society continues on its merry pursuit of limitless affluence and growth.”11

Trainer isn’t the only academic who sees growth and energy as inextricably entwined. Recently, DISNOVATION collaborator Baruch Gottlieb sent me a presentation by Jean-Marc Jancovici, in which the climate expert links post World War II GDP growth directly to the amount of energy we release into the earth, pointing out in no uncertain terms that the kind of continuous growth promised by politicians is incompatible with reducing our dependence on fossil fuels. “There’s absolutely no way we can address climate change with the correct order of magnitude, which is [reducing] the world’s emissions by three in thirty years, without triggering a world recession,” he says to an uncomfortable audience of economists. “Today saying that we are serious about climate change and that we will [still] have growth (…) is a big fat lie.”12

What can we do about this contradiction? Trainer’s solution is what he calls the “simple way,” or, in less euphemistic terms, drastically reducing consumption levels to 10% of their current levels. While this might be more of a provocation than a serious proposal, Trainer’s own dedication to this way of life—he doesn’t fly and grows his own food—supports, at least anecdotally, political scientist Cara New Daggett’s assertion that, rather than sitting back and waiting for renewable energies and new technology to save the day, we need “new ways of thinking about, valuing, and inhabiting energy systems.”13

“It’s important to move away from the idea of energy as a metaphor ‘tinged with virtue’ and towards a concept of energy as a ‘scientific entity’ with a material imprint. This, I would argue, is where artists like DISNOVATION come in.”

The problem, Daggett explains in the introduction to her 2019 book The Birth of Energy: Fossil Fuels, Thermodynamics, and the Politics of Work, is that because the term “energy” is bound up in with the “pleasures of modern life” and any discussion about reducing our consumption habits seems to suggest “the denial of the higher planes of civilization and life.” It’s precisely for this reason, she argues, that fossil fuel extractors call themselves energy companies. “Energy seems to invite grand thinking,” Daggett writes. “… Oil, gas, and coal have become the villains on a warming planet, but who could be against energy?”14

In order to change this dynamic, it’s important to move away from the idea of energy as a metaphor “tinged with virtue” and towards a concept of energy as a “scientific entity” with a material imprint. This, I would argue, is where artists like DISNOVATION come in. As well as being storytellers, artists have a unique ability to give shape to otherwise intangible concepts and notions. With many of the works in “Post Growth,” for example, the collective use coins made from PET Plastic—itself the result ancient sunlight concentrated in organic materials over millions of years—to represent different units of energy, such as the amount of sunlight15 that falls in one year in different cities across the world. In doing so they make clear the shortfall between the energy we produce and the energy we spend. The hope is that, by holding these units of energy in their hands, viewers can no longer ignore their own part in our rapidly warming world.

“If humans unavoidably desire ever more energy, then what could we do short of hoping for a technological miracle, changing the human condition, or colonizing other planets? Assigning responsibility means recognizing how fossil-fuel systems work to favor certain interests, whether in Europe and North America, or in the distinct fossil-fueled visions of new industrializing states like China, India, or Brazil. Understanding the politics of fossil fuel domination is a necessary prerequisite to developing alternative energy values and institutions that are adequately just and radical.”

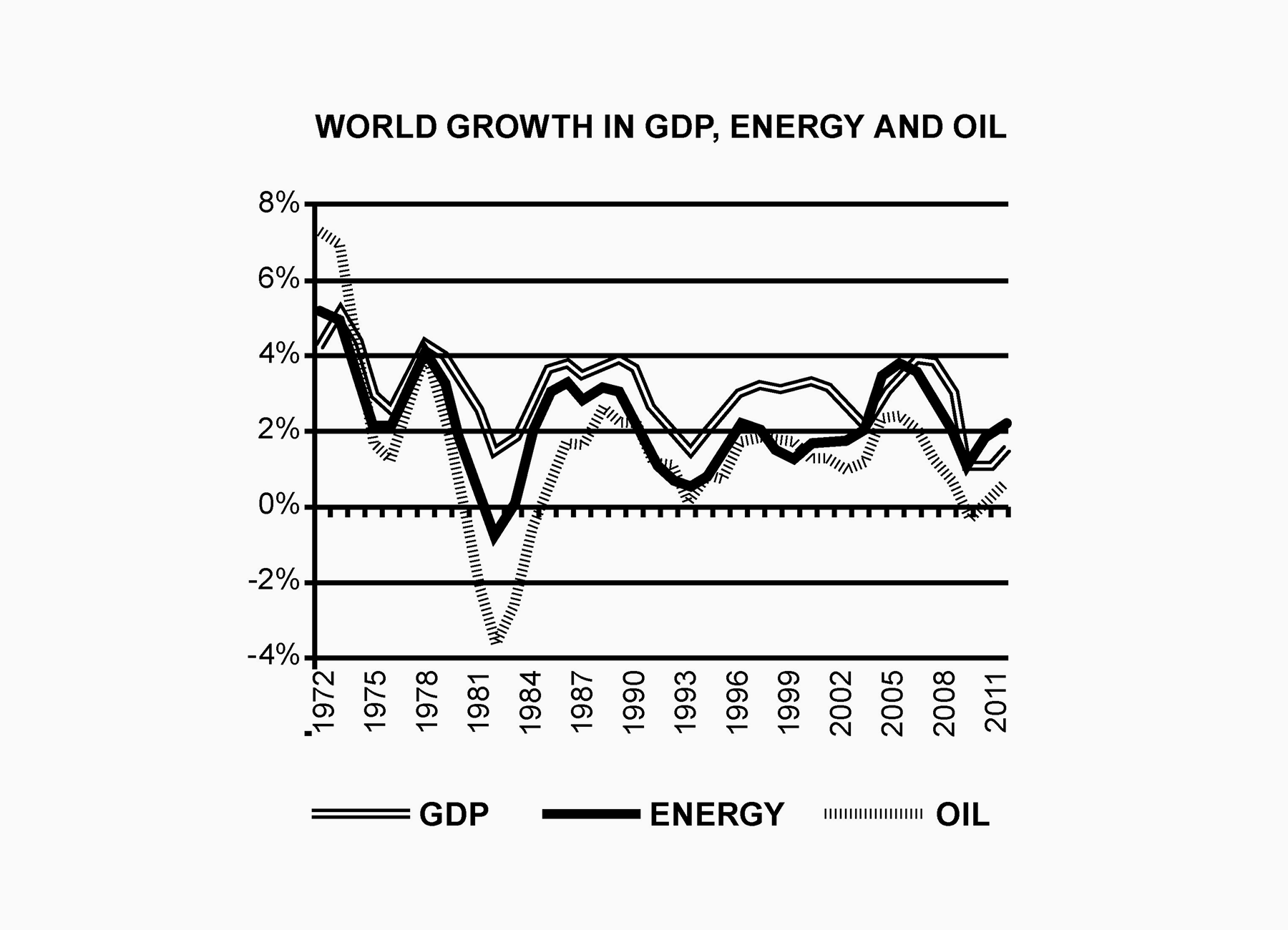

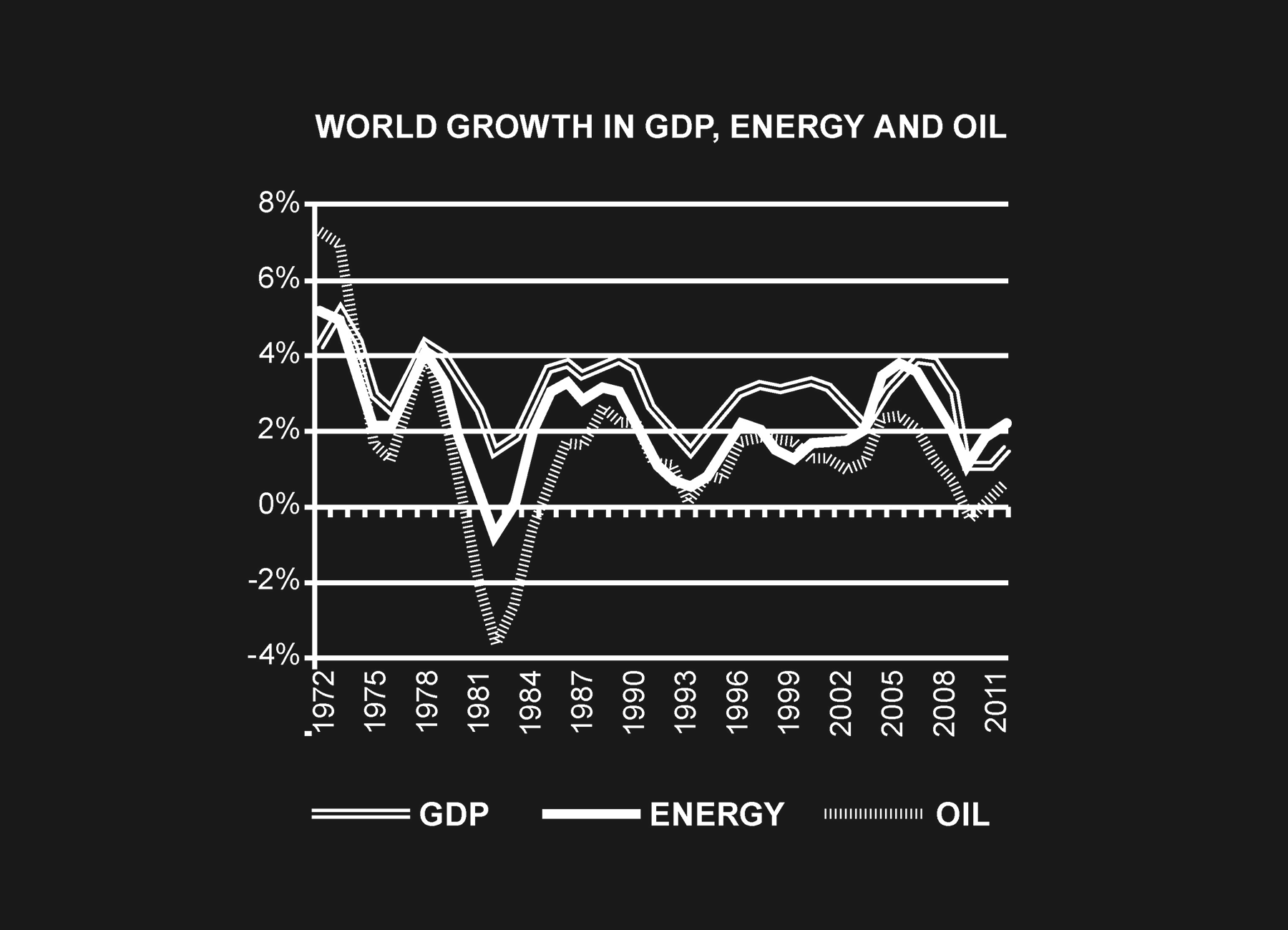

In an article first published in the French journal Le Débat in September 2012, energy and climate expert Jean-Marc Jancovici underscores the correlation between GDP growth, energy, and oil consumption. “Energy is the blood of industrial societies,” he writes. “What counts is not its price, but availability: energy is now what drives our economic activity far more than work or capital.” In a series of charts, which DISNOVATION adapted for “Post Growth”, Janvocici demonstrates how that dependency has only increased in recent decades. In 1998 and 2005, for example, the slowdown of oil production preceded the fall of GDP and the subsequent economic crashes—“it is not because of the crisis that we use less oil, but because oil availability has decreased that we have a crisis.”

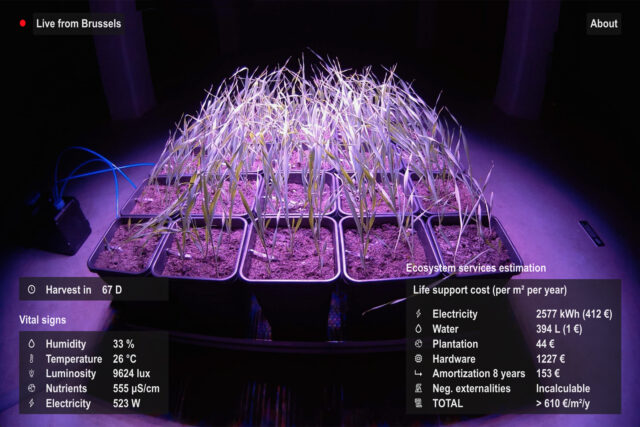

Solar Share – The Farm (2020)

DISNOVATION.ORG & Baruch Gottlieb

“This 1 square-meter experiment of automated cultivation makes manifest the vast technical infrastructure and energy required to grow such staple as wheat in an artificial environment.”

“Vertical farms in cities can produce—profitably—hydroponically grown leafy greens, tomatoes, peppers, cucumbers, and herbs, all with far less water than conventional agriculture requires. But the produce contains merely a trace of carbohydrates and hardly any protein or fat. So they cannot feed cities, especially not megacities of more than 10 million people. For that, we need vast areas of cropland planted with grains, legumes, and root, sugar, and oil crops, the produce of which is to be eaten directly or fed to animals that produce meat, milk, and eggs. The world now plants such crops in 16 million square kilometres—nearly the size of South America—and more than half of the human population now lives in cities. […] Vertical farms can’t substitute for much farmland, and the claims made for them have been exaggerated.” —Vaclav Smil (June 2018), IEEE Spectrum

Solar Share – The Farm seeks to demonstrate a fundamental and paradoxical challenge to the proposal from agro-industries (and preppers alike) to provide for the nutritional needs of large urban populations in times of climate uncertainties, through grow houses and other artificially controlled environments. This 1 square-meter experiment makes manifest the vast technical infrastructure and energy required to grow such staple as wheat in an artificial environment. In today’s economy, it is profitable to artificially produce agricultural products with high water content such as leafy greens and tomatoes.

However, from a systemic understanding, this apparent profitability depends on the availability of cheap fossil energy, unaccounted for resource extraction and pollution all over the globe, incurred in subordinate processes from mining and electronics manufacture to international freight. The present experiment seeks to reveal the numerous layers of invisible interdependencies and to provide a speculative reference reckoning of the incalculable ecosystem services at play in conventional agriculture.

Solar Share – The Farm (2020), DISNOVATION.ORG & Baruch Gottlieb, installation, 1m2 of automated cultivation, LED grow lights, camera, video streaming

“It reminds us we are connected to the other beings on this planet—and that we inherit our ancestors’ decisions and future generations will live in a world designed by our actions.”

As a curator and an editor, Clémence Seurat investigates the fields of reflection and action related to political ecology. In 2014-15, she was a member of Bruno Latour’s research laboratory in arts and politics based at Sciences Po Paris (Speap) and participated in the conception of The Theater of Negotiations and the curation of associated conferences and resources. She co-founded the collective COYOTE and the 369 Editions publishing house. Within the Sciences Po médialab, Seurat designs programs and edits content for FORCCAST.

“Capitalists and socialists have been fighting for more than a century to get hold of the famous ‘means of production’, all the while being in agreement on the core matter, namely that production constitutes our materiality and that we are obliged to produce in order to feed ourselves. This is why, since the beginning of the pandemic, all leaders—whether they are capitalists, communists or ecologists—have wanted to ‘restart production’. But none of these regimes takes into account our links with the other-than-human world because they don’t think they live alongside them, or rather they consider these to be ‘secondary’ to the production that is supposed to constitute our materiality.”

“We’re having a 50 year anniversary of the moon landing in the U.S. this year, in which the technologies used to achieve that are still not largely available, and have still not transformed the energy systems in the U.S., and that’s an interesting paradox to look at.”

Valerie Olson researches contemporary sociocultural processes that remake what counts as environments. Her current projects focus on how social groups use the system concept to perceive, organize, and control spatial relations, particularly on large scales. This focus allows her to follow the ways people relate to sites, things, and processes they do not experience directly and which are categorized as outlying or beyond human. She serves on UCI interdisciplinary research teams and campus initiatives such as Water UCI, the Salton Sea Initiative, the UCI OCEANS Initiative, and the UCI Community Resilience program.

A transcript of the video can be found here. For more “Post Growth” interview segments with Valerie Olson visit postgrowth.art.

If conventional wisdom and media narratives are to be believed, then it’s only a matter of time until we transition to sustainable energy: as older, dirtier energy sources are phased out, they’ll be replaced by newer, cleaner ones. Data shows, however, that changes in energy consumption have seen the use of all sources (clean or otherwise) increase, instead of transitioning towards sustainability. “Although the percentage shares of biomass, coal and oil in our energy supply have fallen with the rise of alternatives, their total use continues to grow,” researchers Richard Newell and Daniel Raimi told Axios in 2018. “The world has never experienced an energy transition, but the challenge of climate change means that, for the first time, one will need to begin.” One of several diagrams produced for the “Post Growth” exhibition, this chart debunks the transition myth. “The rhetoric needs complete reframing,” the artists state. “The challenges the energy transition represents need to be rethought beyond science and engineering but as part of a broader reconsideration of our modes of living, values, infrastructures, and social situations.”

“Those who suggest we may want to consider other slow-growth paths are shouted down as Luddites or environmental extremists or are dismissed as being ignorant of basic economics… or even as being ‘anti-growth,’ as if what we need is more growth. Notice, though, that the shouting-down is done mainly by those at the top of the growing pyramid of ‘wealth,’ which threatens to suffocate our planet.”

“There is conflict in a forest, but there is also negotiation, reciprocity, and perhaps even selflessness.”—Ferris Jab, on the work of ecologist Suzanne Simard, in “The Social Life of Forests,” The New York Times

A few years ago, the writer and alt-right hero Jordan Peterson took some time out from ‘owning the libs’ to tweet his thoughts on a new study on ant behaviour. “30% of the ants do 70% of the work,” he wrote. “Not a consequence of the West, or capitalism, in case it needs to be said :)” It wasn’t the first time that Peterson has looked to the animal kingdom as an apologia for capitalism. The Canadian pundit is also fond of using lobsters to argue that hierarchies are ‘natural’ rather than the result of social constructs that give some groups power over others.

As anyone who spends time in the ‘manosphere’—a group of blogs and message boards populated by Incels, men’s rights groups, and pick-up artists—will know, the behaviour of wild animals is often used within these spaces to explain away the worst impulses of our species. Wolf pack behaviour, for instance, is frequently extrapolated onto humans, with the most obvious example being the popularity of the term ‘alpha’ to positively describe a male who is dominant in social or professional scenarios.16 But as many have pointed out, much of this thinking is based on a Darwinist theory of evolution, one which pits all living creatures against each other for limited natural resources while ignoring the many examples of non-human behaviour that “verges,” as a recent New York Times article put it, “on socialism.”17

Titled “The Social Life of Forests,” the article in question is based on the work of Canadian ecologist Suzanne Simard whose research on subterranean networks between fungi and trees “upended” the idea of trees as “solitary individuals [that] competed for space and resources.”18 Instead, she found that “while there is indeed conflict in a forest, there is also negotiation, reciprocity, and even selflessness.” In the mid-90s, Simard’s research was seen, in the male-dominated field of forestry, as “girly.” The fact that over 15 years later it’s still controversial—some researchers see “reciprocal exploitation” in place of Simard’s “big cooperative collective”—shows how invested many people still are in a dog-eat-dog view of the world.

”What all of these works have in common, from Serre’s treatise on the humble parasite to Haraway’s brand of ecofeminism, is a move away from the idea that humans are categorically different from all other living beings.”

But what if, instead of using ethology, as Peterson does, to reaffirm our human-centric perspective on life, we looked to nature for ideas of how to do things better—particularly when it comes to growth? In one of his Post Growth Toolkit interviews, Geoffrey Bowker does just that. Finding inspiration from the collective thinking of ants, he argues that horizontal decision-making could be the best way to combat climate change. “There’s no solution that’s going to come from central government in any of this,” he says. “It’s going to be us, as a species, rethinking who we are, reworking who we are, replanning who we are and then rippling that out across the whole sets of relationships that we have. That’s what we see ants doing enormously successfully.”

Bowker’s thinking is informed by decades of research and writing on cross-species relationships by well-known figures such as Michel Serres and Donna Haraway, as well as younger academics like Merlin Sheldrake and Anna Tsing, both of whom recently released books on mushrooms. What all of these works have in common, from Serre’s treatise on the humble parasite to Haraway’s brand of ecofeminism, is a move away from the idea that humans are categorically different from all other living beings. If we can first get our heads around this shift, then, as Bowker recently told me “a rainbow of new outcomes becomes available.”

“Our comforting sense of the permanence of our natural world, our confidence that it will change gradually and imperceptibly if at all, is the result of a subtly warped perspective. Changes that can affect us can happen in our lifetime in our world—not just changes like wars but bigger and more sweeping events. I believe that without recognizing it we have already stepped over the threshold of such a change; that we are at the end of nature. By the end of nature I do not mean the end of the world. The rain will still fall and the sunshine, though differently than before. When I say ‘nature,’ I mean a certain set of human ideas about the world and our place in it.”

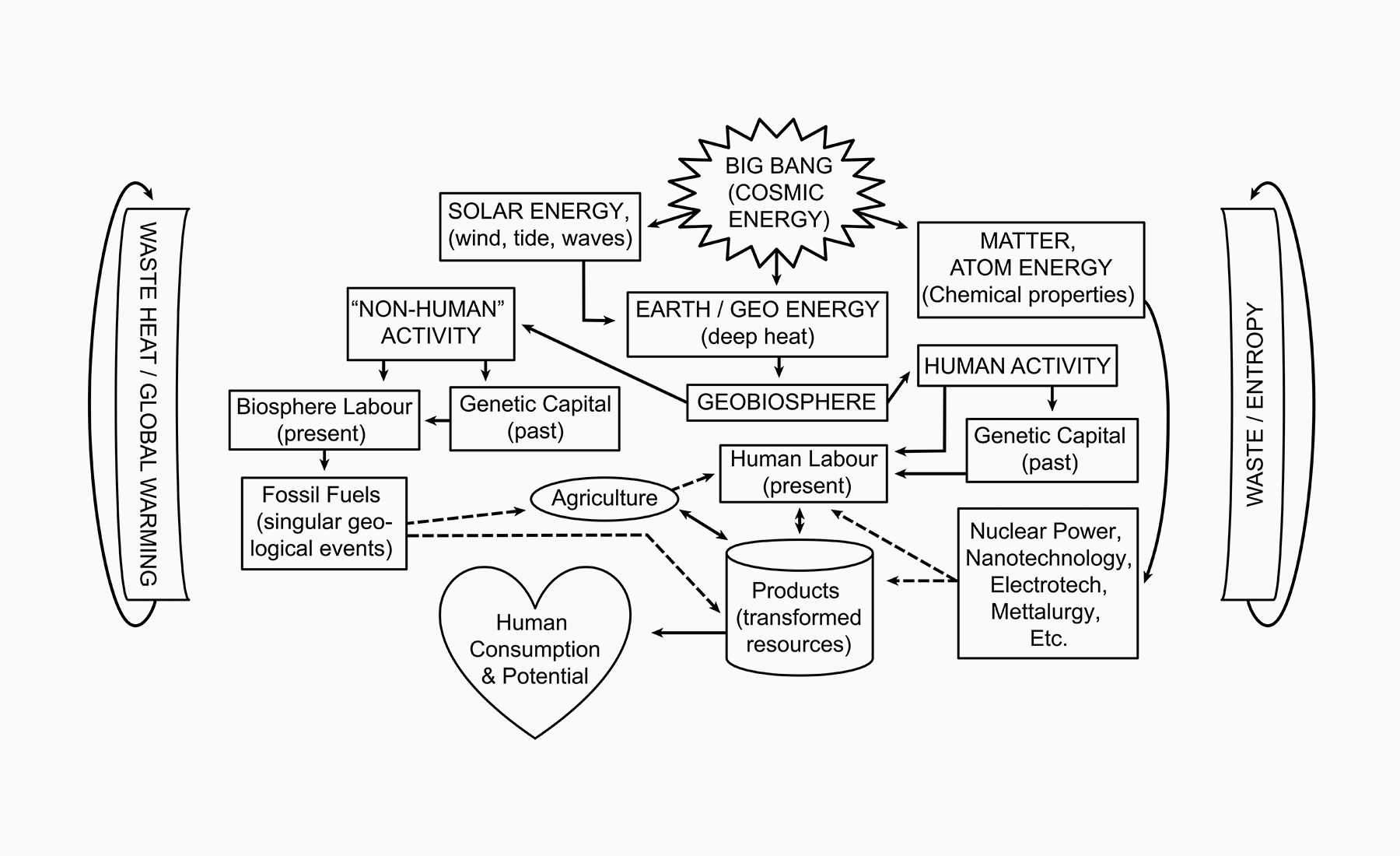

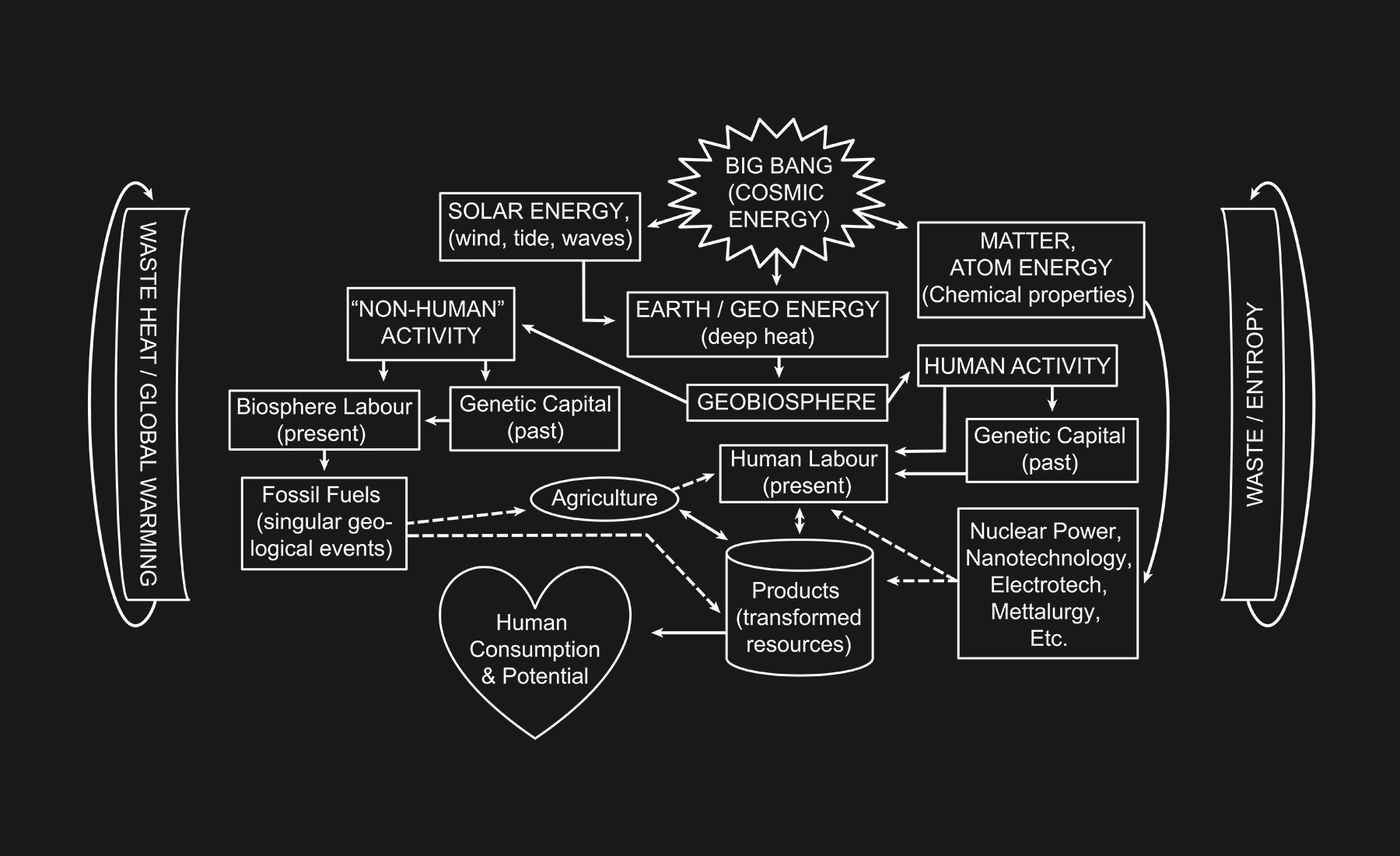

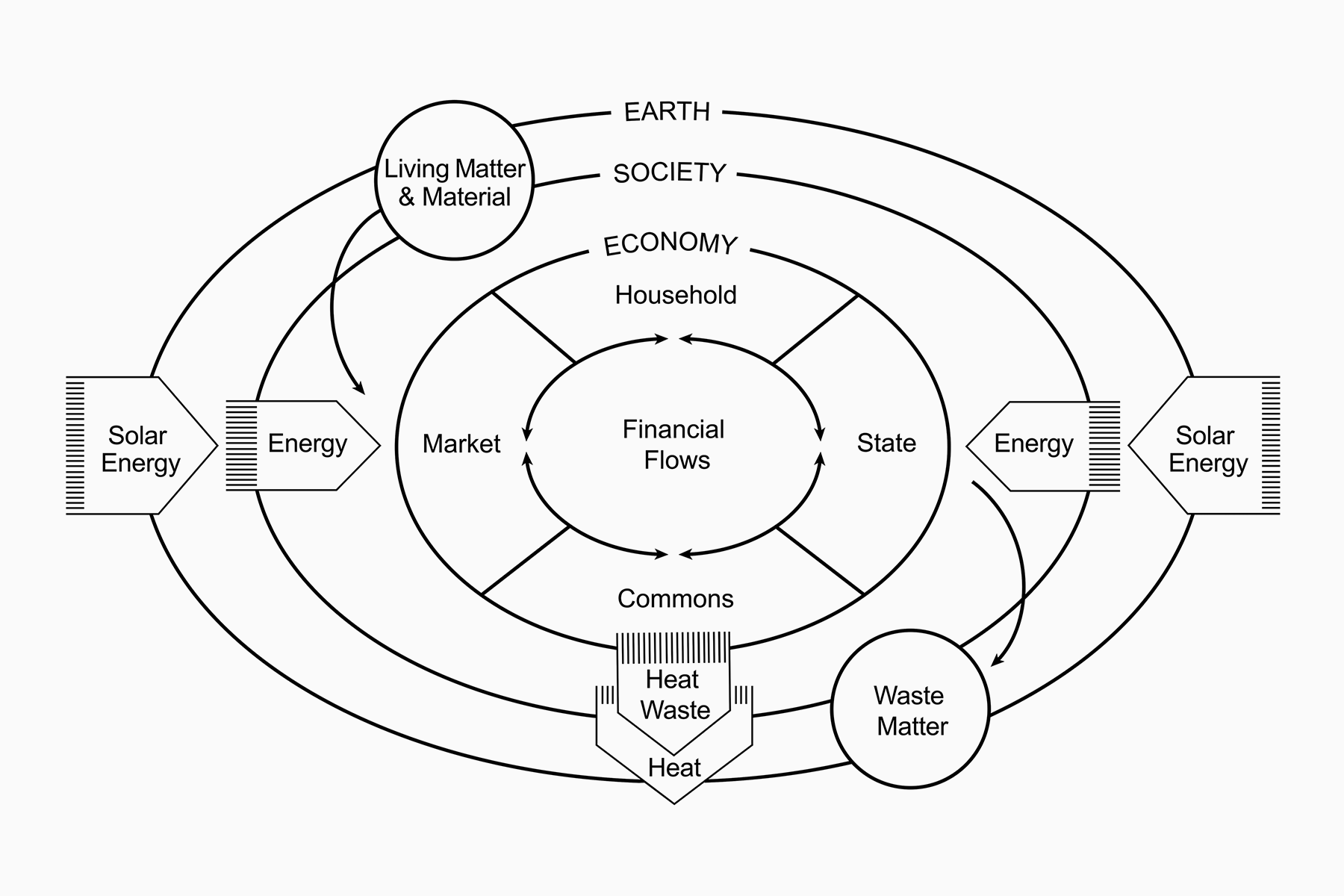

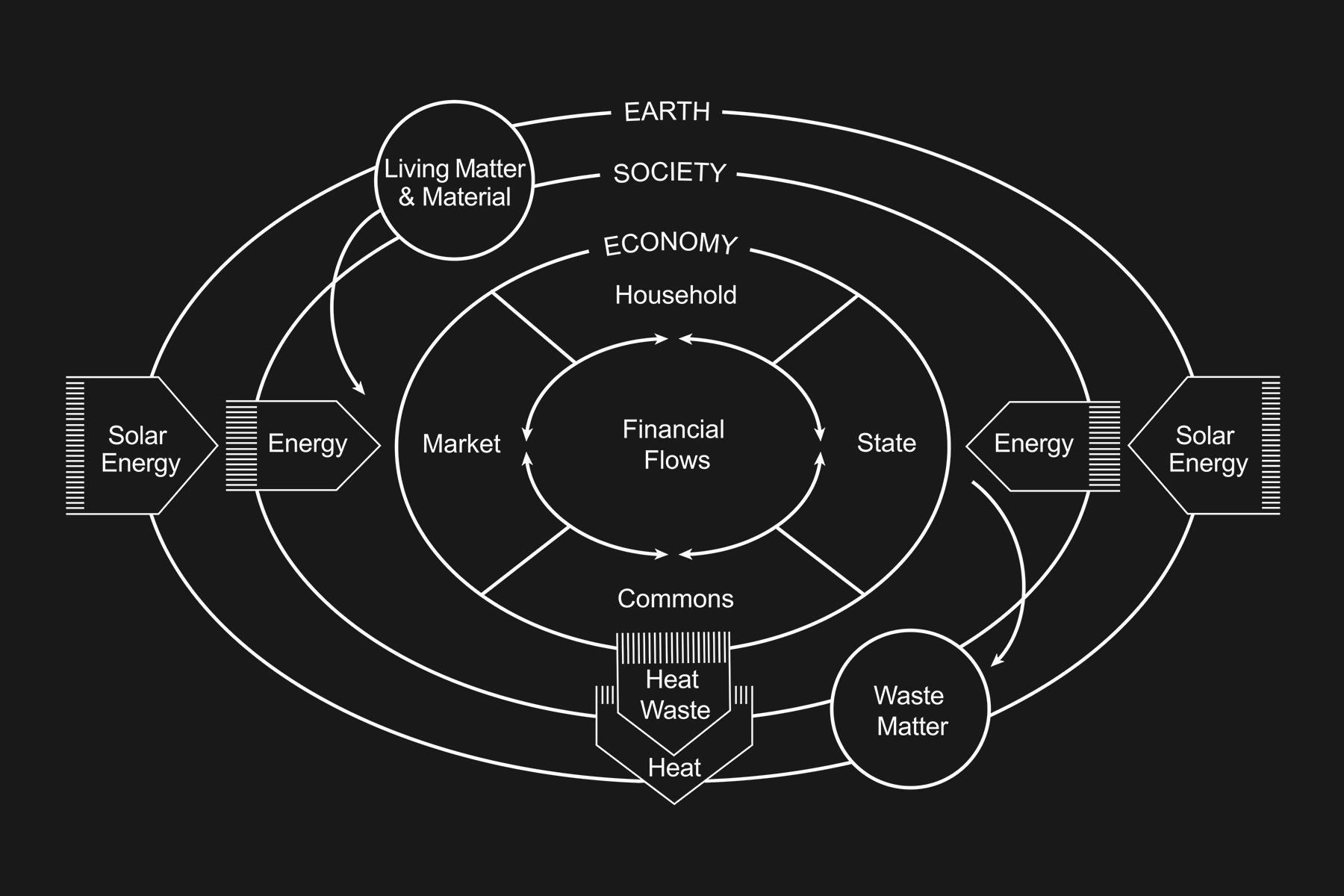

Part of the speculative Solar Share project that is at the heart of “Post Growth,” the Solar Share: Energy Flow Diagram attempts a ‘deep sustainability analysis’ that encompasses all human and non-human contributions. At the top are epochal sources related to the big bang, solar radiation, reserved deep heat, and chemical properties in the materiality of the Earth. Extending from these rich sources that provide all the energy for the nutritive and technical needs of human beings today, are long-term cyclical processes which eventually furnish everything we consume. Framing the central diagram are representations of waste and entropic dissolution—both black boxes unto themselves, whose complexity extends beyond the scope of this schematic.

Solar Share – The Coins (2020)

DISNOVATION.ORG & Baruch Gottlieb

“How might our understanding of economics change if the instruments we used for money had an equivalent value to the solar energy required to materially produce them?”

Howard T. Odum’s (controversial) concept of ‘emergy’ attempts a comprehensive accounting of the energy consumed in direct and indirect contributions to make a product or service. Emergy allows for extremely slow and vast processes to be acknowledged as vital contributions to life, which we can no longer take for granted in an age of accelerating technological advances. Solar energy emerges as central in energy modelling, responsible for most of the sources of energy we rely upon today, including wind, tides, and, fossil fuels.

Some areas of the world get more sunlight than others, some ‘use’ more sunlight than others. In Europe, we are able to use considerably more energy than we receive naturally from the sun through imports in various concentrated forms, principally petroleum, coal and natural gas. According to The World Bank Group’s Global Solar Atlas, Brussels is one of the least sunny cities in Europe, receiving only 3 kWh/m2 on an average day, and only 1000 kWh/m2 a year. Yet Brussels’ energy consumption is comparable to that of most European cities.

Solar Share coins are made of PET plastic, a petroleum bi-product that constitutes ancient sunlight concentrated in organic material over millions of years. A few grams of PET have the same embodied energy as a square metre of yearly solar irradiation in Brussels.

How might our understanding of economics change if the instruments we used for money had an equivalent value to the solar energy required to materially produce them? As a speculative response, each Solar Share coin embodies the average solar irradiation received at a specific urban location.

Solar Share – The Coins, (2020), DISNOVATION.ORG & Baruch Gottlieb, installation, plexiglass frames, coins made of plastic waste (Precious Plastic, PET)

“If I have any allegiance with respect to the future of the planet it is not particularly with humans—it is with the manifold ways in which life produces intelligence, beauty, and sociality.”

Geoffrey C. Bowker is Professor at the School of Information and Computer Science, University of California at Irvine, where he directs a laboratory for Values in the Design of Information Systems and Technology. Recent positions include Professor of and Senior Scholar in Cyberscholarship at the University of Pittsburgh iSchool and Executive Director, Center for Science, Technology and Society, Santa Clara. Together with Leigh Star he wrote Sorting Things Out: Classification and its Consequences (1999); his most recent book is Memory Practices in the Sciences (2005).

“Attempting to freeze evolutionary change by creating natural reservations misses the point: we need to maximize the ability to speciate, to grow—by concentrating on conservation we make bad decisions for the long-term health of the planet.”

“If we appreciate the foolishness of human exceptionalism, then we know that becoming is always becoming with—in a contact zone where the outcome, where who is in the world, is at stake.”

“How do you induce somebody or a group of people to suddenly see the world differently? You don’t just do it by hitting them over the head with facts, you do it by telling stories, you do it by sketching out possible futures.”

Geoffrey C. Bowker is Professor at the School of Information and Computer Science, University of California at Irvine, where he directs a laboratory for Values in the Design of Information Systems and Technology. Bowker’s books include Sorting Things Out: Classification and Its Consequences (1999, authored together with Susan Leigh Star) and Memory Practices in the Sciences (2005), both published by the MIT Press.

A transcript of the video can be found here. For more “Post Growth” interview segments with Geoffrey C. Bowker visit postgrowth.art.

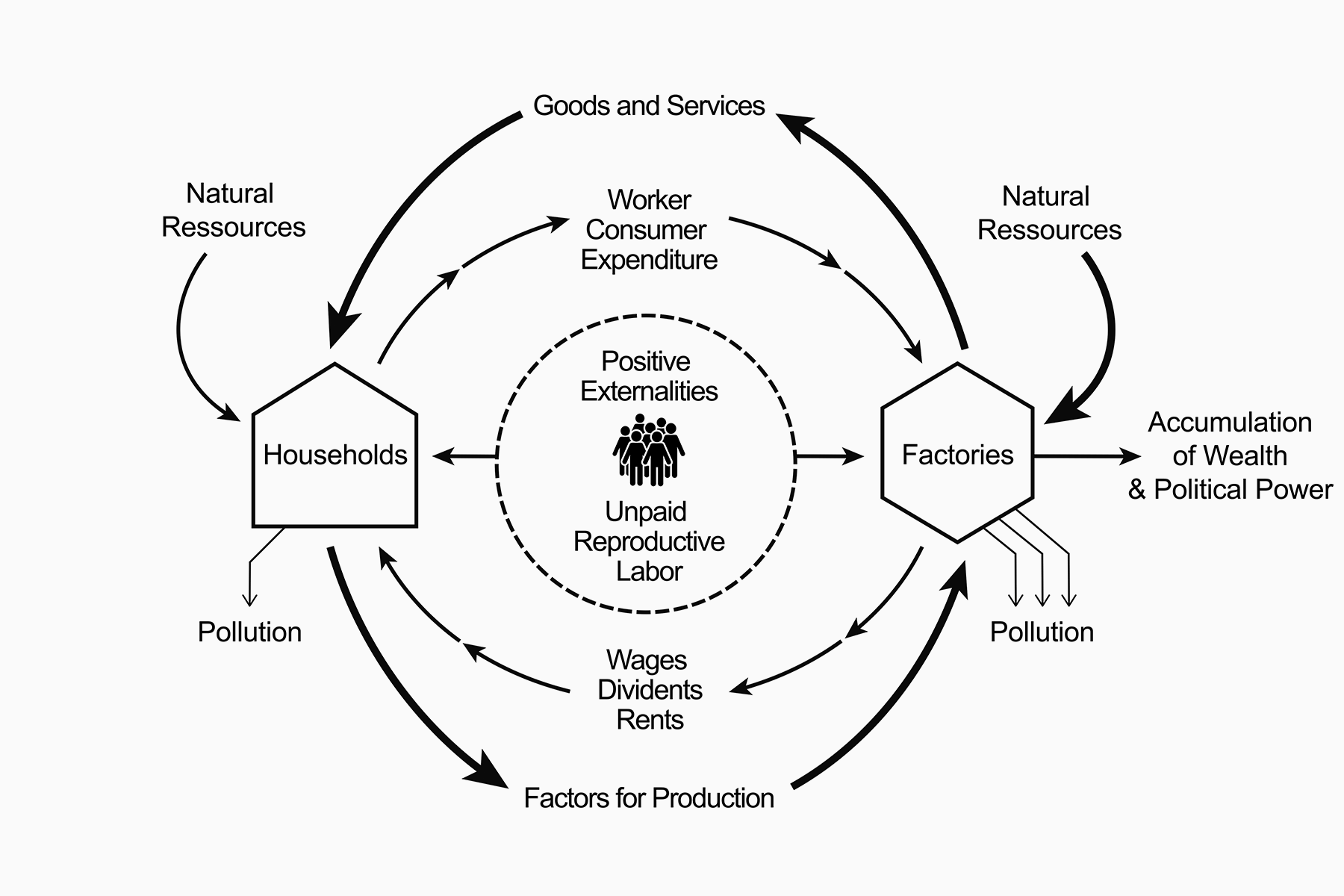

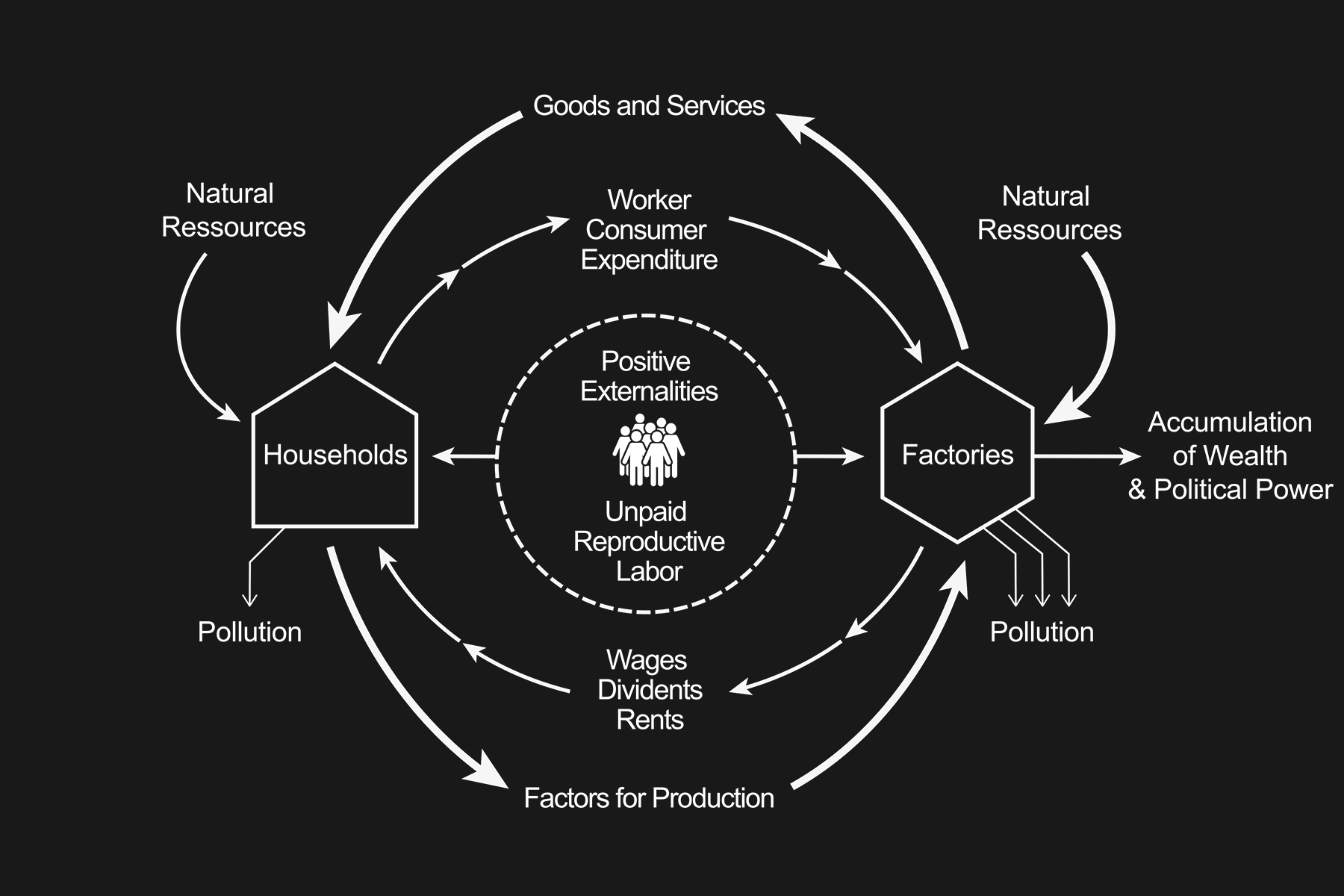

“There is a discrepancy between the approach of economists to environmental protection and the approach of nearly everybody else,” wrote the Nobel Prize-winning American economist Thomas C. Schelling in his 1983 book Incentives for Environmental Protection. It lays out how pricing incentives such as charges on emissions; in contrast to regulatory standards, can be shaped into a practical policy that is technically effective, politically enactable, administratively enforceable, and equitable. To this day, the environmental impacts of industrial activity remain unaccounted for as what economists call externalities. The inputs provided by the planet’s ecosystems are similarly ignored. American ecologist Howard T. Odum’s Emergy accounting method provides a radical alternative. Developed in the 1990s, and informed by his work on general systems theory, Emergy describes an eco-economical model based on Embodied energy, wherein the totality of the energy required to produce goods and services—the sunlight that makes plants grow, the cosmic forces that forged Earth’s precious metals—is considered. It posits that natural systems and anything in them retain “energy memory” that, technically, goes all the way back to the Big Bang. “Emergy is a measure of energy used in the past and thus is different from a measure of energy now,” Hodum writes. “The unit of emergy (past available energy use) is the emjoule, as distinguished from joules used for available energy remaining now.”

“Emergy describes an eco-economical model based on Embodied energy, wherein the totality of the energy required to produce goods and services—the sunlight that makes plants grow, the cosmic forces that forged Earth’s precious metals—is considered.”

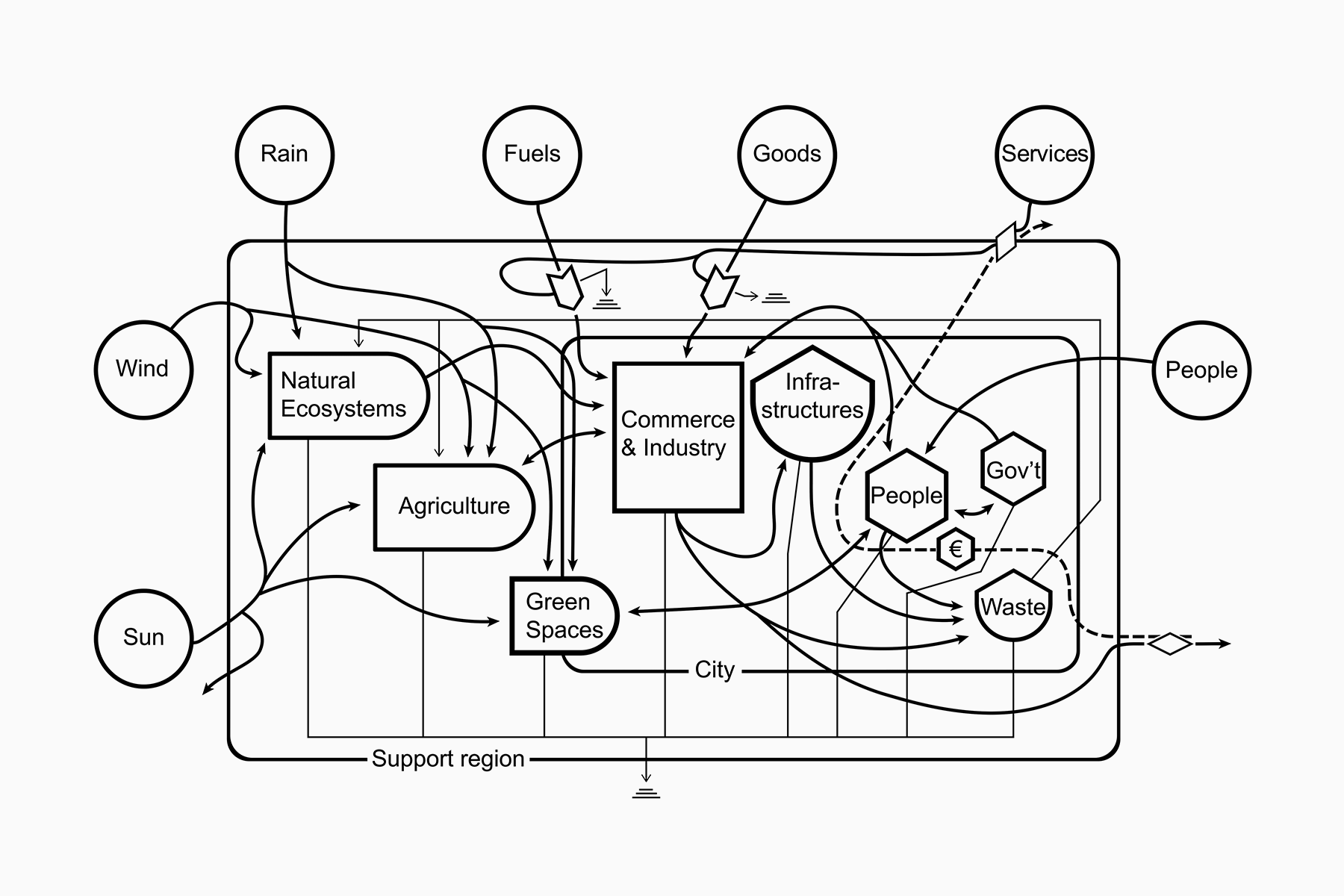

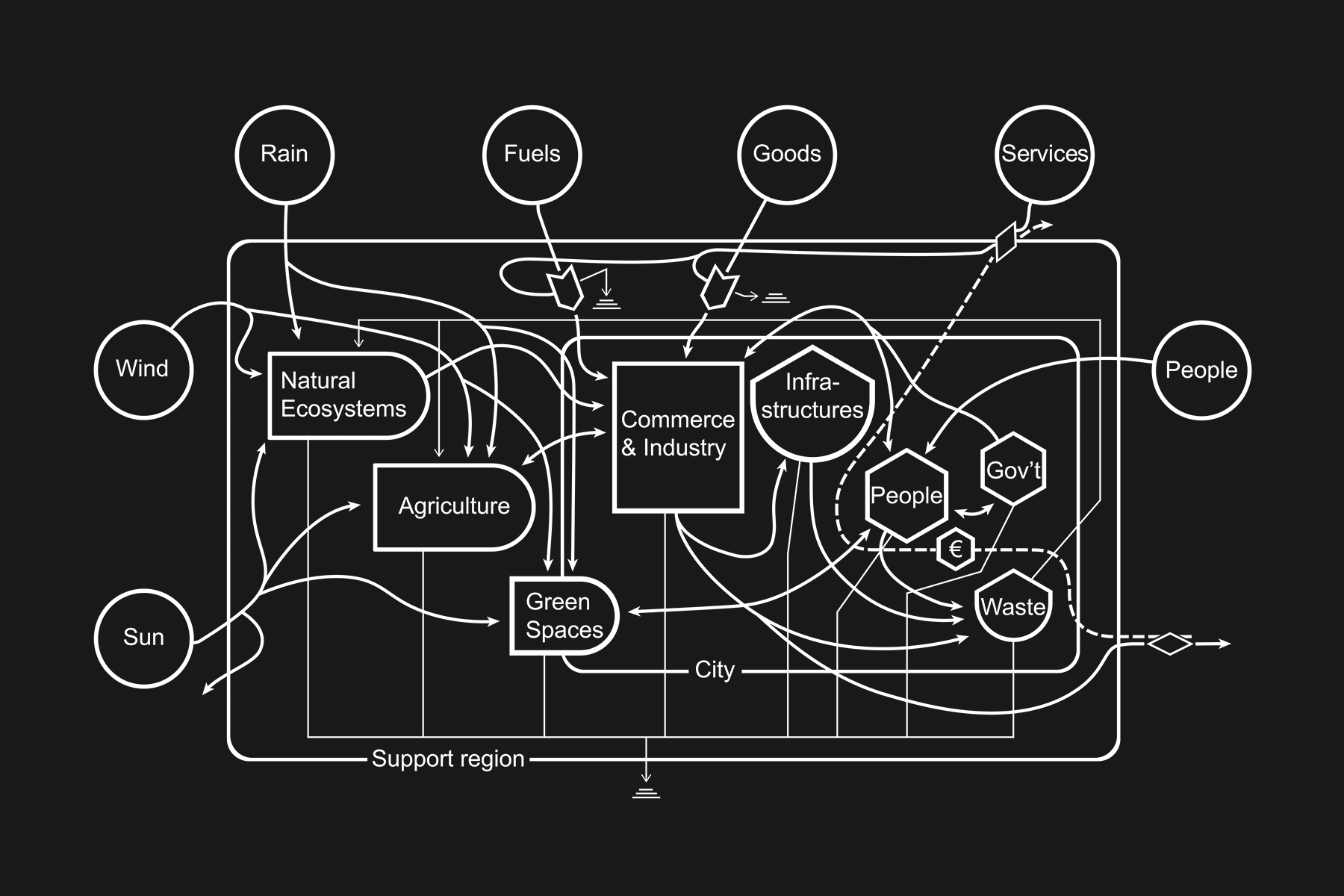

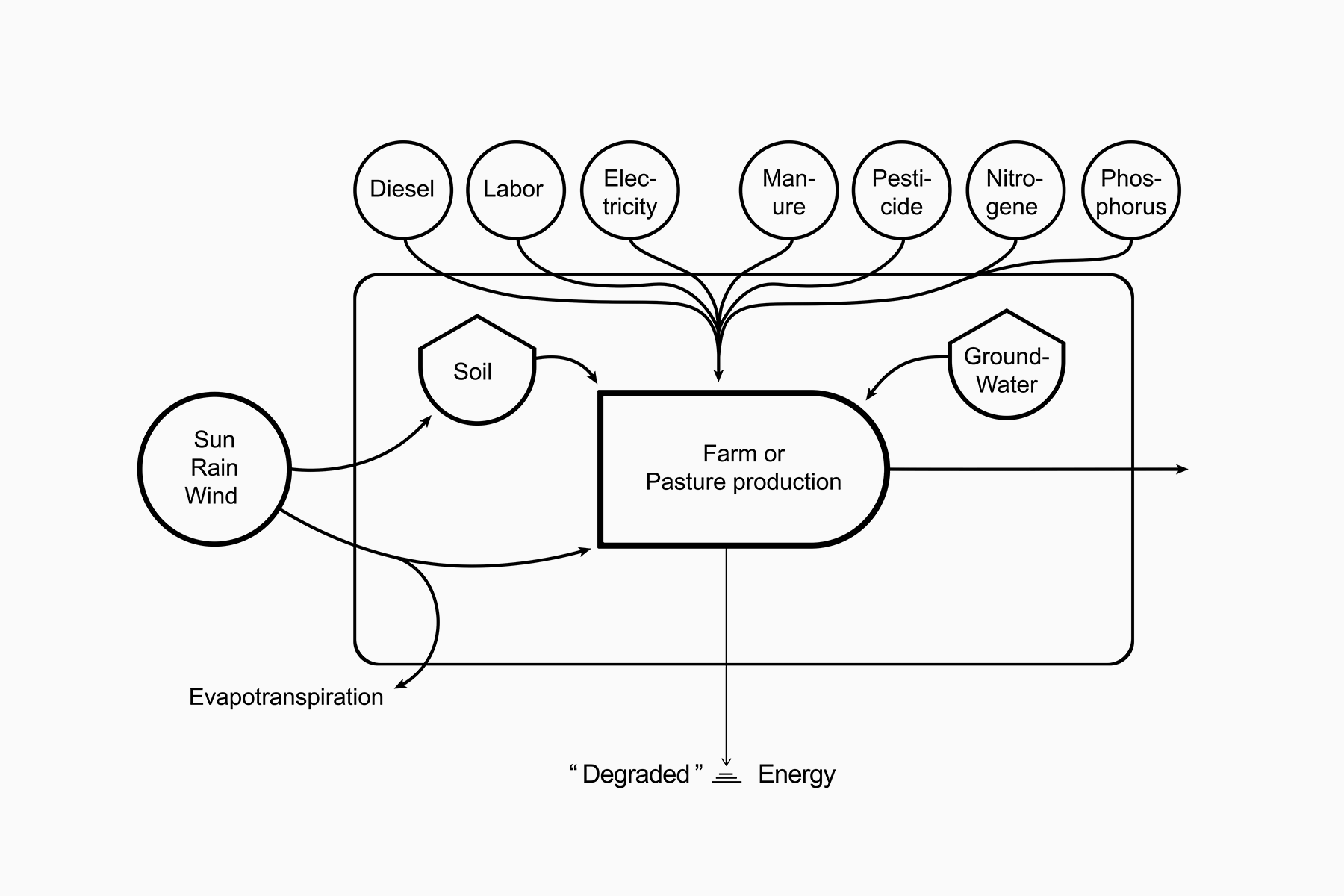

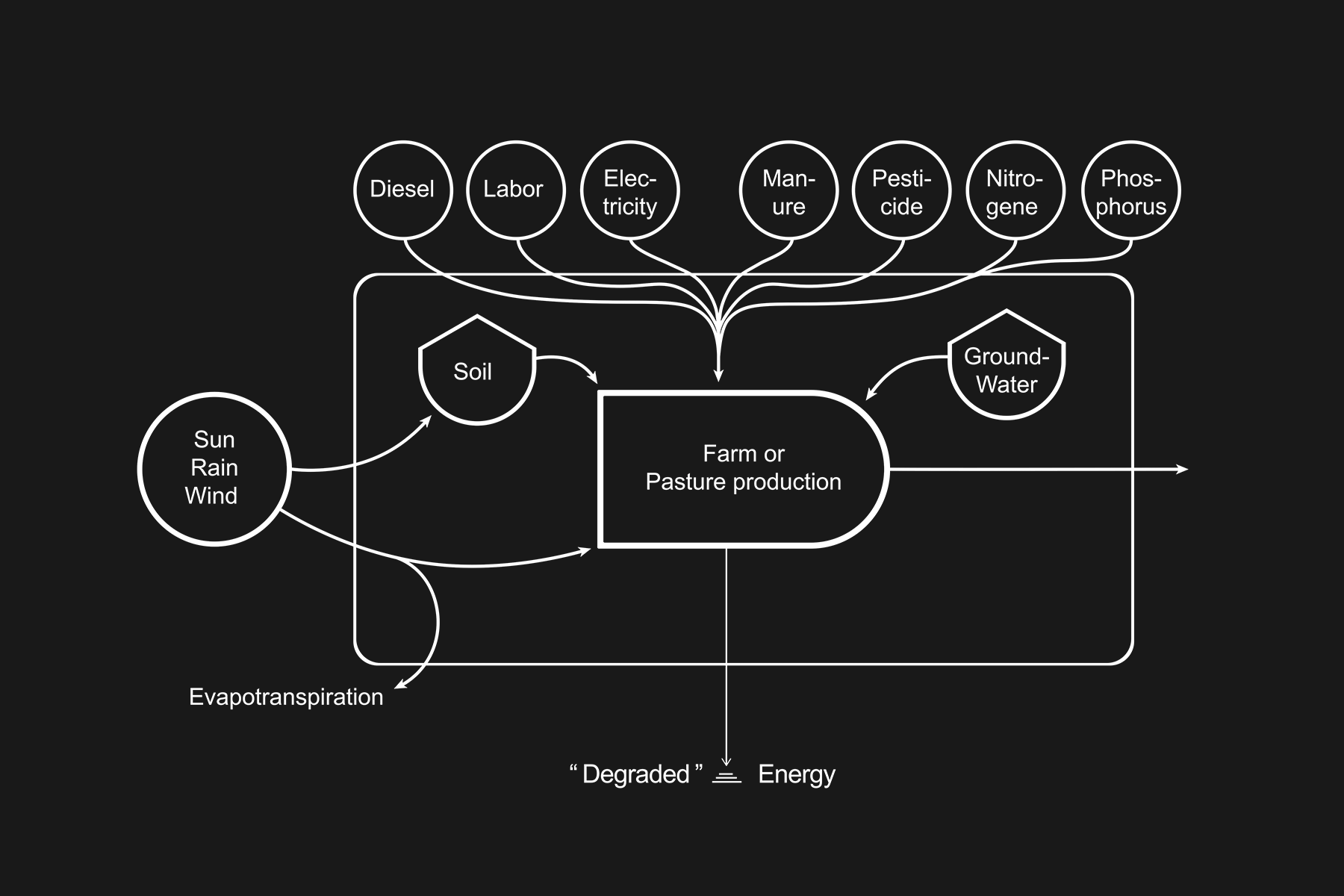

For “Post Growth,” DISNOVATION.ORG and Baruch Gottlieb translated Odum’s model into two diagrams, one representing industrial activity (top) and the other agriculture (bottom). They demonstrate that we act as neither individuals nor independently, but rather enmeshed in extensive networks of embodied energy flows. What would an economic system look like if Odum’s “solar energy-equivalent unit” was applied throughout, as the artists have done here? Would it better account for our deep entanglement with the biosphere and the material affordances we rely on?

“Imagining the human since the rise of capitalism entangles us with ideas of progress and with the spread of techniques of alienation that turn both humans and other beings into resources. Such techniques have segregated humans and policed identities, obscuring collaborative survival. The concept of the Anthropocene both evokes this bundle of aspirations, which one might call the modern human conceit, and raises the hope that we might muddle beyond it. Can we live inside this regime of the human and still exceed it?”

“The U.S. has the biggest GDP in the world, but it ranks only 18th on the happiness scale—a pie in the face for economists or politicians who insist that GDP is the best way to measure progress.”

Determined to not let lockdown blues get the better of me, I started 2021 by buying myself a gratitude journal. Turquoise and hardbound with gold lettering on the cover, this rather beautiful object has quickly become part of my morning routine, and while I wouldn’t say it’s changed my life, I have noticed that taking a few minutes each day to write down what I’m grateful for has produced a subtle shift in how I think. In the past, I’ve been guilty of treating success as a constantly moving goalpost, but regular journaling has encouraged me to celebrate even the smallest of wins, which, during lockdown, might be as simple as preparing myself a healthy lunch or checking in on a friend.

It might sound a little sentimental, but what my new routine has taught me is to value internal as well as external growth. It’s a realization that I’m sure anthropologist Valerie Olson, who I quoted in the introduction to this dossier, would be happy to hear. Speaking with DISNOVATION for the project’s interview series, Olson argued that western society has a “prejudice or a bias toward thinking about growth externally,” which blocks us from “using other knowledges than western knowledges to think about internal growth, or internal transformation as being another valuable focus for energy.”

Watching this interview again, I couldn’t help but think of the UN’s World Happiness Report, which measures countries on factors such as social help and freedom to make life choices rather than solely on their GDP. Unsurprisingly, it’s poor countries in long protracted conflicts, such as Yemen and Afghanistan, which fair the worst, but the fact that it’s Finland that has won the top spot for the last three years suggests that the size or power of a country has a limited effect on the happiness of its citizens. Take the U.S. as an example. It has the biggest GDP in the world, closely followed by China, but it ranks only 18th on the happiness scale—a pie in the face for economists or politicians who insist that GDP is the best way to measure progress.

What if, instead of focusing on production capacity and economic growth, we started to take attempts to measure internal transformation more seriously? What would change if the American media reflected on these reports rather than mock or underplay them, such as one article in which the author called a Pew Research Center survey “complete crap” because Nicaragua was above “wealthy Japan”?20 One result might be that more countries adopt universal healthcare, free education, and a higher minimum wage, all of which are common in the countries that repeatedly top these lists. It might seem like a pipe dream right now, but it’s something that we should strive for, nonetheless. To quote a motivational phrase from my gratitude journal: “Whether you think you can, or you think you can’t—you’re right.”21

In April 2020, during the first wave of COVID-19, Amsterdam’s city government announced it would recover from the crisis, and avoid future ones, by embracing the theory of ‘doughnut economics.’ Introduced by University of Oxford economist Kate Raworth in a 2012 paper and popularized in her 2017 book Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist, the economic model is a visual framework for sustainable development. Shaped like a doughnut—or lifebelt—it harmonizes planetary boundaries with human needs. The doughnut’s inner boundary represents the “social foundation,” where everyone’s necessities like food, healthcare, and education are being met. The outer circle describes “environmental ceilings”—air pollution, ocean acidification, climate change—that must not be overshot. The “sweet spot” in the middle is what Raworth defines as a safe and just space where humanity can thrive.

Apolitical and growth-agnostic, Raworth’s framework doesn’t lay out specific policies or goals. Instead, it relies on stakeholders—countries, cities, communities—to decide on doughnut benchmarks and ways of meeting them. Amsterdam, for example, committed to a five-year circular economy strategy that includes measures such as building supportive infrastructure with sharing platforms, thrift shops, online marketplaces, and repair services. The goal is to halve the use of new raw materials by 2030 and to achieve a fully circular economy by 2050. “In a doughnut world, the economy would sometimes be growing and sometimes shrinking,” Raworth explains in a TIME article, as GDP is put in service of reaching social goals within ecological limits, and not viewed as an indicator of success in itself. “When we think in terms of health, and we think of something that tries to grow endlessly within our bodies, we recognize that immediately: that would be cancer.”

“When we think in terms of health, and we think of something that tries to grow endlessly within our bodies, we recognize that immediately: that would be cancer.”

For “Post Growth,” DISNOVATION.ORG and Baruch Gottlieb interpreted Raworth’s theory with two models of their own: one shows how unaccounted externalities like unpaid labour, natural resources, and pollution fit into the standard macroeconomic model (top), and the other how economic activity is embedded within and dependent upon planetary energy flows (bottom).

“Historians of hegemonic U.S. ideologies, from Frederick Douglass and Max Weber through Cedric Robinson, can help us see how the growth imperative is bolstered by racialized theories of human evolution, of capitalism as economy, and of imperialism.”

Valerie Olson researches contemporary sociocultural processes that redefine what count as environments. Her current projects focus on how social groups use the system concept to perceive, organize, and control spatial relations, particularly on large scales. As an assistant professor at the UC Irvine Department of Anthropology, she serves on UCI interdisciplinary research teams and campus initiatives such as Water UCI, the Salton Sea Initiative, the UCI OCEANS Initiative, and the UCI Community Resilience program. She is the author of the book Into the Extreme: U.S. Environmental Systems and Politics Beyond Earth (2018).

“Based on the past four years in this country, growth is also associated with anxious regimes of ‘winning.’ It will take alternative models and imaginaries of how to live to dislodge this imperative.”

“There was something oddly poetic about an exhibition on the dangers of growth being shut down by a global crisis that can, at least partly, be traced back to the farming industry and human encroachment on animal habitat.”

In February, DISNOVATION’s simultaneous solo exhibitions at iMAL, Brussels and 3 bis f, Aix-en-Provence, closed to the public. Both named “Post Growth,” these dual shows explored the interdisciplinary group’s research into alternatives to infinite economic growth, which, as highlighted by the videos, printed matter, installations, and sculptures that were on display, is an attitude that has a direct correlation with climate change. In turn, Life… After the Crash, part of HOLO’s new online series of dossiers, dove into some of the topics raised at these venues in a series of Q&As, short essays, soundbites, readings, and videos.

Based in Berlin, travel restrictions meant that I never actually got to see either version in person, but after a brief period of disappointment, I realized that there was something oddly poetic about an exhibition on the dangers of growth being shut down by a global crisis that can, at least partly, be traced back to the farming industry and human encroachment on animal habitat. (For a great breakdown of the latter problem, I can highly recommend a recent episode of Last Week Tonight with John Oliver on the “next pandemic.”) I was also cheered by the fact that, unlike most exhibitions, “Post Growth” was never intended as a one- or two-time event but was always thought of by the artists as a long-term project—one that could never be contained in a single location or time period.

So, the good news is that even if you didn’t make it to Brussels or Aix-en-Provence you haven’t missed your opportunity to contribute. Further physical editions of “Post Growth” are planned later this year at STRP, Eindhoven and IMPAKT, Utrecht, and the group will also “challenge and develop” their models within the framework of a one-year residence at Louvain-La-Neuve University, Belgium. Beyond this, you can follow their activities online through their dedicated “Post Growth” website, which features videos from their multipart series Post Growth Toolkits, as well as download the elements of The Game, a tactical card game that invites its players to “reprogram [themselves] out of economic growth orthodoxy.” Additionally, it’s also possible to play a more active role in the conversation through the DISNOVATION’s community Discord channel.

“If I’ve got one takeaway from the last few months of being immersed in this topic it is that there is no shortage of bold solutions to our current problems—what’s lacking is the political will to implement them.”

I’d also encourage any of you that haven’t already to read back through the full dossier, which, much like some of the creatures discussed in my “note” on branching Kinship, celebrates a reciprocal relationship with the Post Growth project, in that it is inspired by but also builds upon the research done by DISNOVATION and their collaborators. The dossier is by no means conclusive, but it hopefully offers a comprehensible guide to some of the complex themes brought up by the eponymous exhibitions, from overpopulation to energy use, human exceptionalism to soil diversity. Indeed, if I’ve got one takeaway from the last few months of being immersed in this topic it is that there is no shortage of bold solutions to our current problems—what’s lacking is the political will to implement them. But it doesn’t have to be like this. As Naomi Klein argues in On Fire: The Case for a Green New Deal: “The stories we tell about who we are as a nation, and the values that define us, are not fixed. They change as facts change. They change as the balance of power in society changes. Which is why regular people, not just governments, need to be active participants in this process of retelling and reimagining our collective stories, symbols, and histories.”

References:

(1) Jackson, Tim. “The Myth of Decoupling.” In Prosperity without Growth: Foundations for the Economy of Tomorrow. New York: Routledge, 2007.

(2) Collins, Chuck, Omar Ocampo, and Sophia Paslaski. “Billionaire Bonanza 2020: Wealth Windfalls, Tumbling Taxes, and Pandemic Profiteers.” Institute for Policy Studies, April 23, 2020.

(3) For More on the immensity of Bezo’s wealth see Warren, Kate. “Jeff Bezos Has Gotten $70 Billion Richer in the Past 12 Months.” Business Insider, September 15, 2020.

(4)+(5) Post Growth Toolkits (The Interviews), 2020.

(6) Fuller, R. Buckmeister. “World Energy.” Fortune, February 1940.

(7) Jancovici, Jean-Marc. “How Much of a Slave Master Am I?” Manicore, May 1, 2005.

(8) + (9) Coricone, Adryan. “Eco-Fascism: What It Is, Why It’s Wrong, and How to Fight It.” Teen Vogue, April 30, 2020.

(10) Featherstone, Liza. “Don’t Blame the Babies.” Jacobin, April 15, 2019.

(11) Ted Trainer, The Simpler Way, quoted in Pyke, Toni. “The Energy Debate: Renewable Energy Cannot Replace Fossil Fuels.” Development Education, April 12, 2017.

(12) Jancovici, Jean-Marc. “Averting Systemic Collapse… or Managing It.” OECD Conference Centre, Paris, 2019.

(13) Daggett, Cara New. The Birth of Energy: Fossil Fuels, Thermodynamics, and the Politics of Work. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019. p. 3.

(14) Ibid., p.1.

(15) For more on the concept of “Ancient Sunlight” see Hartmann, Thom. The Last Hours of Ancient Sunlight. New York: Three Rivers Press, 2004.

(16) Squires, Bethy. “Pick-Up Artists Don’t Understand What ‘Alpha’ Even Means—As Evidenced by Wolves.” Vice, October 27, 2016.

(17)+(18)+(19) Jabr, Ferris. “The Social Life of Forests.” The New York Times, December 6, 2020.

(20) Kyle Smith. “That world happiness survey is complete crap.” New York Post, March 22, 2017.

(21) Attributed to American industrialist Henry Ford.