Variations: Iskra Velitchkova

“Vera Molnar’s works speak for themselves … they are subtle, elegant, minimal, and complex all at the same time.”

Iskra Velitchkova is a Bulgarian self-taught computational artist based in Madrid. She focuses her work on generative art but she is interested and inspired by all kinds of interactions between humans and machines. With a background in data visualization, first with her own studio and as a member of different scientific teams, Velitchkova grounds her work in understanding how we can design and use technology to better understand ourselves.

Q: I am curious about how you think early generative art, and Molnar’s work specifically, has influenced your own artistic practice and the contemporary generative art space more broadly. Do you remember where or how you first encountered her work?

A: I think I don’t have a rational or bounded idea of how we are influenced by the pioneers. I feel they’ve somehow impregnated our eyes. It’s hard to imagine generative art (and not just generative art) without thinking of geometric shapes, lines, and abstractions. It’s very hard as well, even if you are not into art, to think about aesthetics without primary colours, minimal shapes, and the legacy that Bauhaus left us. Not to mention, great names from movements totally unrelated to using machines such as Kandinsky, Delaunay, Rothko, Malevich, or Popova. With generative art, we are far from seeing something completely new, because this legacy feels, at least to me, to be deeply rooted in history.

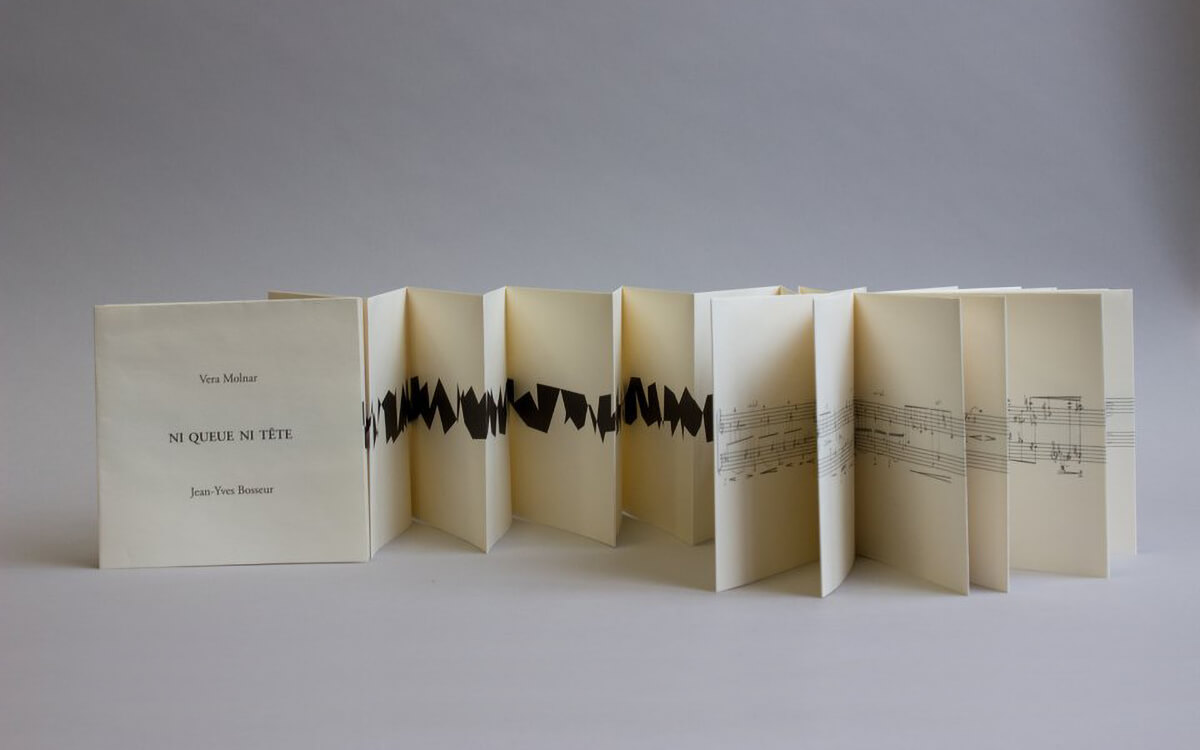

Molnar’s work, in particular, has a very special effect on me. Her works speak for themselves as those silent people who are listened to in the crowd. They are subtle, elegant, minimal and complex at the same time. I don’t know when I first found out about her, but what is exciting and beautiful to see is that recently—thanks to the Spalter Collection or the voice of Jason Bailey, among others—she has been broadly recognized as one of the key figures of the history of computational art.

Molnar’s work, in particular, has a very special effect on me. Her works speak for themselves as those silent people who are listened to in the crowd. They are subtle, elegant, minimal and complex at the same time. I don’t know when I first found out about her, but what is exciting and beautiful to see is that recently—thanks to the Spalter Collection or the voice of Jason Bailey, among others—she has been broadly recognized as one of the key figures of the history of computational art.

Q: I’m not sure if this is something that you want to speak of publicly yet but I heard from a mutual friend that you and your partner recently acquired Vera Molnar’s 2% of disorder in co-operation. I have to ask: what is it like to live with an NFT made by one of the OG generative artists?

A: Yes! Being part of Sotheby’s “Natively Digital 1.3: Generative Art” auction, alongside Vera Molnar, Charles Csuri, Roman Verostko, as well as some of the biggest names in the field today—I’m still processing that it happened. The role of curators today, Anne and Michael Spalter, Sofia García, and IX Shells in this case, brings light to the needed bridges between the future and the past. Their passion and perseverance in crediting each and every pioneer in the field and including the new generations in the narrative inside the space, it’s something that I feel genuinely very grateful for.

I vividly remember the auction. After a few days in New York, we were back at home and it felt like a celebration. No matter what happened, I just wanted to enjoy the moment. We decided to bid on Molnar’s piece, but earnestly, without any expectation that we could compete with the big collectors. At the end, in the last moment, we realized we had placed the highest bid; I had just sold my piece, so it felt like we had to win at all costs. It was such a unique moment to get a historical piece from her—and we did! We celebrated the purchase with a bottle of champagne we bought from Sotheby’s and then some friends joined us.

I cannot say how it feels to us having her piece at home, because it’s not yet here! But we definitely know where it will be placed. Immediately in front of people as they enter through the front door. Vera will be chairing the living room.

I vividly remember the auction. After a few days in New York, we were back at home and it felt like a celebration. No matter what happened, I just wanted to enjoy the moment. We decided to bid on Molnar’s piece, but earnestly, without any expectation that we could compete with the big collectors. At the end, in the last moment, we realized we had placed the highest bid; I had just sold my piece, so it felt like we had to win at all costs. It was such a unique moment to get a historical piece from her—and we did! We celebrated the purchase with a bottle of champagne we bought from Sotheby’s and then some friends joined us.

I cannot say how it feels to us having her piece at home, because it’s not yet here! But we definitely know where it will be placed. Immediately in front of people as they enter through the front door. Vera will be chairing the living room.

Q: Fairly recently, I reluctantly joined Twitter, and I stayed for your plotter drawings, which I encountered thanks to an algorithm. Not only are the works elegant, intricate, and graceful, but it was exciting to see the familiar movement of the plotter pen, in the form of a gif or a video clip, something so physically material interspersed with the hyper-digital generative art on my feed. Could you tell me more about your work with plotters, and how it relates to or is distinct from your digital generative art practice?

A: The plotter work is completely different from my digital work. A few years ago, when I decided to quit my job and begin my journey in art, I spent a year entirely focused on exploring where I wanted to go. I had the clear vision that whatever I would do, it would be connected to and based on technology, but I needed to link to something physical. My work—my life—is always based on roots, connections, and relationships. After several months of theoretical explorations I decided to take action. I bought a pottery wheel without knowing what I was going to do with it, but I started to learn about clay and porcelain. I was so intrigued by how to bring my algorithms into something that is pure and simple as clay. Then I bought a plotter and I started to explore how to use it to paint on the irregular surface. And I just fell in love with it and I forgot my original mission! Both artisan activities allow me to escape from the normal perception of time. The experimentation became the work itself.

“A composition appears on screen in less than a second, but once you plot it, the course of time changes. You can observe for hours and see the rationale behind the drawing—you begin to understand it.”

Generative art has something very different from other art movements. In generative art we explore with a huge lack of control. It sometimes feels like there is some kind of a divine power on the other side. We guide the machine but then the machine gives us an inhuman result—and sometimes it’s cryptic as to how it is made. One way I like to explore this complexity is plotting the output. A composition appears on screen in less than a second, but once you plot it, the course of time changes. You can observe for hours and see the rationale behind the drawing—you begin to understand it. If you use this as a process, the plotter feels like a translator—a teacher—I create a piece, I plot it, I understand it, and then I go back to the computer with stronger directions. And this is why I love to film the process and share it—it feels like a story about time and a dialogue between me and the machine.

I like to compare this process to photography, which I have loved since I was a child. After training the eye for many years, I decided to dive more into the theory of it and learn how the camera actually works. Once I started to explore with the digital camera I realized I didn’t understand anything (the light, the shutter speed, etc.), so I decided to buy a film-based camera. First of all there is huge friction, since you are constrained to a roll, you have to be intentional about each photograph and then develop it. This period opened me to the need to always get to the roots of any activity I do. The plotter is my analogue camera now. You cannot get crazy if you don’t master your tools.

Q: Your website opens with a proposition: “I don’t think we should make technology more human, I believe that we have to push technology forward to understand us better.” This reminds me of Vera Molnar’s attitude toward computing technology; from the beginning, when she was met with criticism for using such a ‘cold’ machine to make art, she argued that using the computer could actually bring us closer to the human aspects of creativity. In what ways have systems, algorithms, and neural networks helped you understand yourself better, as an artist and/or as a human?

A: After many years working and dealing with data, at some point I realized I was more interested in the algorithms themselves than in the data. I had the chance to work with very talented people from whom I learned a lot about the science behind our technological processes today. Techniques like Deep Learning opened to me a new world of possibilities to map our world. Understanding how machines trace our behaviours and classify them into several dimensions (not just the three we are used to), understanding how we are establishing distances between ourselves and our context (which book the algorithm recommends to me, which song, which person). it’s something bigger than what we used to think. It’s about finding a new kind of distance, which is not physical distance but it is still a distance.

I mean, formalizing these connections between us and things we belong to, the people we love or potentially do, it feels like somehow, an unprecedented encyclopedia about ourselves. Even if we are far from having true intelligent machines, we are building the basis for that. I really don’t think all this work has to be focused on a mission to replicate human identity—there are enough people on Earth—but I think technology is how we unlock mysteries. We are limited in our perceptions, we can not even understand our own feelings sometimes. We tend to be more rational because we have learned this is the way we deal with complicated situations; but we are much more than a brain and our emotional side—our passions—guide us ultimately. This is why, my utopian dream, is that after a long history of human explorations and deviations, our ultimate goal is to process who we are and what makes us human. And if machines can help with that, it would be a welcome change.

Variations

Weaving VariationsExplore more of "Variations:"

→ HOLO.mg/stream/

→ HOLO.mg/vera-molnar-weaving-variations/